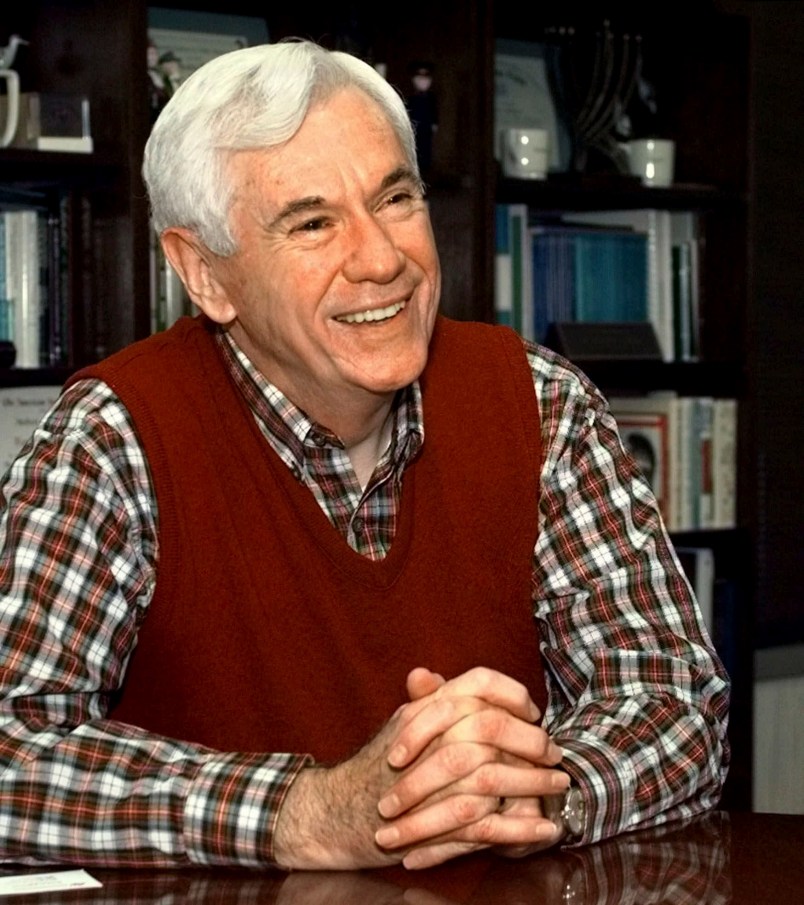

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. (AP) — Former Florida Gov. Reubin Askew, who guided the state through a period of school busing to achieve integration in the 1970s, died early Thursday. He was 85.

Askew died surrounded by family members at Tallahassee Memorial Healthcare, Ron Sachs, a former aide and family spokesman, told The Associated Press.

Askew was admitted to the hospital Saturday, his family said. Over the past three months, he has suffered from aspiration pneumonia, hip surgery and, most recently, a stroke.

Askew rose from obscurity in the Florida Legislature to become the Democrats’ surprise gubernatorial nominee in 1970 and then beat the incumbent Republican, Claude Kirk.

His eight years in office coincided with the end of the Vietnam War, Watergate and dramatic social change across the nation. He was a liberal on racial issues and crusaded for overhauling the state’s tax laws, open government, environmental protection, ethics legislation and streamlining the courts and other governmental agencies.

Upon being elected governor, Askew immediately called a special session of the Legislature to put on the ballot a constitutional amendment for a corporate income tax. Askew stumped the state in support of the measure that voters adopted by a 2-1 margin.

In his first year, he also won passage of penal and judicial overhaul, including classification of alcoholism as a disease and the nonpartisan election of judges.

“His primary accomplishments were in the field of moral leadership, rather than building monuments,” said the late Allen Morris, a former House clerk who later served as state historian until his death in 2002 at the age of 92.

He did manage at least one monument — a new 22-story Capitol.

Askew championed racial and gender equality. He integrated the Florida Highway Patrol and appointed the first black in 100 years to the Florida Cabinet and the first black Supreme Court justice.

In 1975, he pardoned two black men, Freddie Pitts and Wilbert Lee, who had spent 12 years in prison, including eight on death row, after being wrongly convicted of killing a pair of white service station attendants in the Panhandle town of Port St. Joe. It was a decision that cost Askew votes in the Panhandle — his home region — when he ran for re-election.

He appointed the first woman to the Cabinet and supported the Equal Rights Amendment, but Florida lawmakers failed to ratify it, a major disappointment for him.

Askew began the practice of using nominating commissions for judicial appointments to limit political influence. The commission system subsequently was enshrined in the Florida Constitution.

Askew also introduced a system in which the state Supreme Court justices and appellate court judges face the voters every six years to see if they should be retained.

“Our government can’t work if you do not have an independent and competent judiciary,” Askew said in 2012. “It is the best system that’s been devised for fairness.”

His leadership was tested when the Legislature, over Askew’s objection, ordered a straw ballot on a proposal to ban busing to integrate Florida’s schools in 1972. Busing by then had become a hot national issue resulting in protests and, in some cases, violence.

Two years earlier, Kirk had declared forced busing illegal in Florida. He also dismissed Manatee County’s school board and superintendent to prevent them from complying with a federal judge’s desegregation order. That resulted in a brief standoff between U.S. marshals and state and local law enforcement officers, but Kirk backed down when U.S. District Judge Ben Krenzman fined him $10,000 a day.

Askew campaigned against the busing ban but voters approved it by 74 percent during the March 1972 presidential primary. He prevailed on lawmakers to add a second ballot question favoring equal education. It passed by an even bigger margin and took the steam out of the antibusing proposal.

The issue drew national attention to Askew, who later that year gave the keynote speech at the Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach. Presidential nominee George McGovern asked Askew to be his running mate, but he declined.

Askew briefly ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 but dropped out after finishing last in the New Hampshire primary. He also toyed briefly with running for the U.S. Senate in 1988 but was uncomfortable with the rigorous demands of fundraising.

Looking back on his campaigns during a 1998 interview, Askew compared it to his days with the 82nd Airborne.

“It’s like jumping out of airplanes,” said Askew, a soft-spoken man who didn’t smoke, drink or cuss. “I don’t ever want to do it again.”

Askew’s political career began when was elected to the Florida House in 1958 and the Florida Senate four years later, but the Panhandle lawyer was virtually unknown when he ran in the Democratic gubernatorial primary in 1970. The popular refrain was “Reubin who?”

But he defeated Attorney General Earl Faircloth in the Democratic runoff and then ousted Kirk in the general election.

After being re-elected with 61 percent of the vote in 1974, Askew pushed for ethics legislation. When lawmakers balked, he collected 220,000 signatures to place his “Sunshine Amendment” on the 1976 ballot.

Adopted with 80 percent support, it requires public officials to disclose their incomes and net worth and bars former officials from lobbying their old agencies for two years after leaving.

In 1978, Askew led a campaign that defeated a proposed amendment to legalize casino gambling. Voters, caught up in the “no” fever Askew helped generate, however, also defeated a complete slate of constitutional revisions including some of Askew’s pet proposals such as an appointed Cabinet and Public Service Commission. In his last year, Askew was able to get the appointed PSC through the Legislature.

“I didn’t think I was particularly remarkable,” Askew said in a 1998 interview. “I was just there.”

Reubin O’Donovan Askew was born on Sept. 11, 1928, in Muskogee, Okla., the youngest of six children. His father abandoned the family and, when Askew was 8, his mother, Alberta, moved to Pensacola, her hometown.

She supported the family by working as a waitress, seamstress, hotel housekeeper and home baker. Askewhelped by selling magazines door to door. He also shined shoes, bagged groceries, delivered newspapers and sold his mother’s baked goods. He also found time to be a Boy Scout, play the tuba and take part in high school politics.

“He always talked strongly, believe or not, about being governor,” said a brother, Roy.

Askew went to the Christian Science Church with his mother as youth and became a Presbyterian shortly before marrying Donna Lou Harper of Sanford in 1956. They adopted two children, Angela and Kevin, who were teens during his years as governor.

He joined the paratroopers in 1946 and then used the GI Bill to attend Florida State University, where he was elected student body president. After graduation he re-entered the service, eventually becoming an Air Force captain before earning a law degree from the University of Florida.

After leaving office, Askew practiced international law in Miami and served 15 months as President Jimmy Carter’s trade ambassador before becoming a teacher, moving in the mid-1990’s to Florida State University where the school of public administration and policy is named for him.

___

McGhee reported from Atlanta.

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.