WASHINGTON (AP) — A dispute between the CIA and the Senate that flared into public view this week has no obvious path toward criminal prosecution and may be better resolved through political compromise than in a court system leery of stepping into government quarrels, legal experts say.

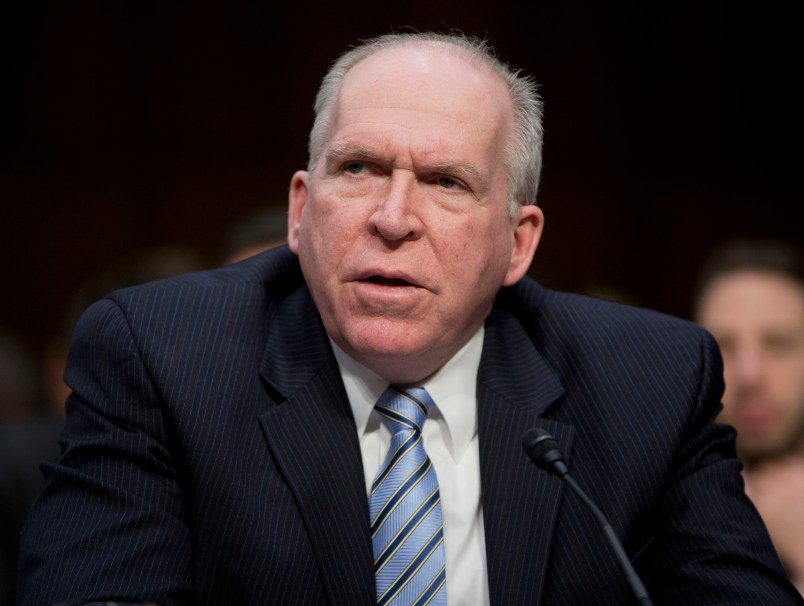

The fight was fully aired Tuesday when Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., in an extraordinary Senate speech, accused the CIA of improperly searching a computer network the spy agency had set up for lawmakers investigating the George W. Bush-era interrogation program for suspected terrorists. CIA Director John Brennan denied the allegations, saying he’d asked for the computer audit to determine whether there was a security breach on the computers used by the Senate staff.

The matter has landed in the lap of the Justice Department, which has been asked to investigate whether laws were broken.

But legal experts say prosecutors will be hesitant to wade into a separation-of-powers dispute between two branches of government that involves a muddled area of the law and raises as many policy questions as it does legal ones. The Justice Department receives far more requests to open criminal probes than it chooses to pursue. Federal courts, too, are reluctant to referee power disputes between the two other branches of government.

“There’s an ongoing debate about what the proper role of each of these branches of government is,” said Jennifer Granick, director of civil liberties at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society. “Who’s watching the watchers? Is Congress watching the CIA or is the CIA watching Congress? And who’s in control here?”

If prosecutors were to get involved, they would confront murky legal questions. Any inquiry would turn on highly specific facts, which are still in dispute, about whatever agreement on computer access existed between the CIA and the Senate Intelligence Committee, whose staff produced a 6,300-page report on allegations of CIA torture during the Bush-era war on terror.

At the committee’s request, the CIA provided 6.2 million pages of material on CIA-provided computers. But Senate investigators noticed that documents they once had been able to access had vanished from the computers. Brennan said he asked for the audit of the computer system after finding that Senate investigators may have improperly obtained sensitive documents.

In her floor speech, Feinstein cited possible violations of the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment, which bars unlawful searches and seizures, as well as a presidential executive order prohibiting the CIA from conducting domestic spying. She also singled out the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, an often-used but contentious statute that makes it a crime to use a computer without, or in excess of, authority.

“This is a disagreement among the branches at a high level, but I doubt that there’s going to be criminal charges,” said Orin Kerr, a George Washington University law professor and former computer crimes expert at the Justice Department. “It’s not obvious that there’s a criminal violation.”

Kerr said it was not clear in the dispute who controls the access to the computers or whether the CIA’s access to the computer system would have been illegal.

The computer fraud statute has figured in, among others, the cases of Army Pvt. Chelsea Manning, who gave documents to WikiLeaks; whistleblower Thomas Drake, a former NSA official who disclosed government waste and fraud to a reporter; free-information activist Aaron Swartz; and Lori Drew, a Missouri woman who was convicted for her role in an Internet hoax involving a 13-year-old girl who hanged herself.

But the law also has been derided as ambiguous and overly broad, and federal appeals courts have split on how it should be interpreted. In Drew’s case, a judge tossed out her misdemeanor convictions, citing the law’s vagueness.

One thing that clouds the law’s use in the CIA case is its exemption, cited by Brennan in a letter last month to Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., for any authorized intelligence agency investigation.

Exactly what “authorized” means “is not defined, and it has produced a lot of uncertainty in a number of cases, and has been accused of encouraging prosecutorial excess because of the lack of definition,” said Stewart Baker, a former National Security Agency general counsel who also served as assistant secretary for policy in the Homeland Security Department.

Baker said arguments could be made for criminal prosecution if either the Senate staff went beyond what it was authorized to do on the computer network or the CIA exceeded agreed-upon limitations on its authority to examine the computers used by the Senate staff. But he said he’d be “very surprised if indictments resulted, unless it’s quite clear that the parties who were doing this knew that they were acting in excess of the understanding and were doing it surreptitiously.”

Frederick Hitz, a former CIA inspector general, said he sees the airing of the dispute as a sign that members of Congress, including those like Feinstein who have been supportive of intelligence agencies, will be stepping up their oversight of those agencies. “It is not going to be a happy period,” said Hitz, who now teaches at the University of Virginia.

Executive encroachments on Congress’ turf can provoke strong reaction on Capitol Hill.

The last major clash involved the FBI’s unprecedented raid on a lawmaker’s office in the Capitol complex as part of a 2006 corruption investigation. A federal appeals court ruled that the search of then-Rep. William Jefferson’s office was legal but that investigators reviewed legislative documents in violation of the Constitution.

While the Justice Department appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, there was relief on both sides when the justices declined to get involved. Jefferson was eventually convicted and is serving a 13-year prison sentence.