This article is the result of a collaboration between TPM members and journalism graduate students at NYU. Over the past several months, NYU students from 10 different countries solicited the help of the community in TPM’s member forum, The Hive, to identify stories that could be of interest to TPM readers, but exist outside the range of TPM’s typical coverage areas. During the course of reporting, the students shared their progress with members for feedback and input. The project was intended to be fun, collaborative, and bring a new and valuable perspective to TPM’s community. Members can read more about the project here and we would love to hear your feedback.

Will Stephen leans back in his chair, a pained smile on his face. Now in his fifth season as a writer for Saturday Night Live, Stephen admits the daily challenge of satirizing a figure as bizarre as Donald Trump — a president who feels like the creation of satirists — has grown stale. “I feel angry or sometimes depressed more than I do ready to write or make a joke,” he says.

For those outside the comedy world this may feel like a hollow complaint. In fact, Stephen says the comment he gets most about his job is, “You must be having a ball with all this politics stuff. It must be so fun!” But when part of your job is to point out the ridiculousness of powerful people, to subvert authority by rendering it absurd, a personality like Donald Trump can be overwhelming.

“It’s hard,” Stephen explains. “Part of the fun of political satire in the past has been mocking people’s self-seriousness — getting to the truth of what politicians are trying to hide about themselves. With Bush or Palin or Al Gore or any of them, you’re poking fun at something that they don’t really want you to see. But with Trump, I don’t know that he is that way. He just is a raw nerve. There’s not a lot hidden there in terms of who he is.”

It’s a sentiment many politically oriented comedians share. New York stand-up comic Boris Khaykin says Trump “has been generally bad for comedy.”

Whether you like the president or not, he explains, “there’s a bunch of stuff that’s already funny about him. So it’s hard to do comedy about comedy. It’s blue on blue — it doesn’t come off. And Trump is not only a target, but also a source. So many of these late-night shows, instead of writing jokes, they just play a clip [of the president] and they’re like, ‘Can you believe it?’ And it’s like, ‘We’re three years in. I can believe it.’”

The ways American comedians make fun of Trump are well known and oft-repeated. They react incredulously to the wacky things he says — a preferred tactic of late-night hosts like Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel, or Trevor Noah. They imitate the way he speaks, sometimes without even changing the content of his statements — something SNL’s Alec Baldwin-led cold opens have been criticized for. They joke about his hair, his skin color, his hands, his bankruptcies, his Twitter typos, his deference to strongmen.

It’s been clear for a while that political satire in the U.S. has a Trump problem. The jokes are getting redundant, but even worse, the president seems immune to them. Even when jabs “work” and Trump feels compelled to respond to them, do those really count as “wins”? In 2016, when enough people made fun of Trump’s small hands, he reacted by assuring Americans — from the Republican debate stage — that there was “no problem” with the size of his penis. The country moved on and Trump won the GOP nomination.

The English author and editor William Cook calls this phenomenon the Trump Paradox: “the more you talk about something, however negatively, the more popular it becomes.” As a result, much of the satire being produced about the president feels toothless and ineffective.

But perhaps American political satire is too focused on the president himself. As NYU Journalism graduate students from the U.S., Pakistan, Argentina, and Chile, we thought we could bring an interesting perspective to this question by examining how satire is handled in countries where a history of authoritarian(ish) leadership has forced comedians into alternative plans of “attack.”

Rather than coming straight at the heads of state or impersonating them, we’ve observed that satirists in Pakistan, Argentina, and Chile critique elements of the government and the systems that enabled leaders’ rise to power. They also target the people who surround and abet those leaders. In doing so, they move beyond mere roasting and make more specific, more incisive commentaries about their political circumstances.

Of course, this approach isn’t unique to any particular country, and American satirists can look to it as a path worth further exploration. Some already are. Jason Adam Katzenstein, a cartoonist at The New Yorker, warns that it’s easy to get sucked into doing comedy just about Trump, but that doing so risks viewing the president not “as a symptom of a larger system, because it probably feels better to not examine what got us here and just say, ‘Look at this one ridiculous person.’”

Katzenstein says it’s important for him and his peers to “make jokes in a way where people can direct their attention away from Trump. Having an interest in making work about that other stuff is step #1.” In other words, what if satirists turned their spotlight on society and the culture surrounding Trump rather than on Trump himself?

In the spirit of examining ways to satirize that “other stuff,” we talked to Pakistani and South American comedians about the techniques they employ — and how they fit within the American political comedy landscape.

Satire in Pakistan, marked by the subtle use of irony and symbolism, can only be understood in the context of the country’s long history of political upheaval. Since its independence from the British in 1947, Pakistan has endured several military dictatorships — the most recent of which ended in 2007 — while no democratically elected prime minister has completed a full term. Throughout it all, the military has remained the most powerful institution in the country, able to influence politicians and the media alike.

This has led to a substantial amount of censorship within the media, which is kept under careful watch by authorities. As a result, comedians have to be shrewd about how they approach certain issues, like military rule or Islamization. The underlying theme, of course, is a deep focus on society: questioning widespread beliefs rather than specific institutions or figures.

In a recent interview, Zeeshan Hussain, a producer of one of Pakistan’s most popular political satire shows, Khabarnaak, highlights how the program’s satire is rooted in the masses. Because certain political or military subjects can’t be targeted directly, satirical attention is turned toward the public. Taboo topics are creatively portrayed through “distant references” to everyday life, and the general public becomes the star (or villain) of the show.

“We don’t attack [targets] directly,” Hussain explains, “but we pick the characteristics of the bureaucracy and assign these attributes to our generic characters.”

For instance, one of Hussain’s skits highlights the consequences of the government’s militarism, as well as the absurdity of allocating more resources to weapons than to basic needs like education — a reality that, he tells us, many in Pakistan accept. It features a jingoistic man explaining the logic behind that kind of resource allocation: if you put money into education, people become more educated and demand more jobs. But spending on weapons preserves the status quo and guarantees “eternal peace.” As Hussain puts it, the segment mocks how “we [starve] to make bombs but then bombs are not used; they’re just shown.”

Sketches like this have made Khabarnaak “Pakistan’s most popular news-based comedy show,” according to Elizabeth Bolton, who penned a recent PhD thesis on Pakistani satire at the University of Texas at Austin. Against the backdrop of political, military, or religious forces who use “all resources at their disposal to muzzle” criticism, Bolton writes, Hussain’s show has managed to play “a key role in the spectrum of news and current affairs analysis.”

There are certainly examples of American comedians taking an artful, subtle look at society to make a point about politics in the age of Trump. Will Stephen singles out SNL’s “Black Jeopardy!” sketch with Tom Hanks, aired weeks before the 2016 election, as a successful commentary on the society that would go on to elect then-candidate Trump.

According to Stephen, that piece “had a thesis to it,” an “original statement”: that disaffected, ignored white American Trump supporters didn’t feel all that dissimilarly to black Americans.

“There was some solidarity there in terms of ‘We’ve been ignored by the elites,’” says Stephen. “That was the thesis of it, and that wasn’t a point that was being made.” Whether it portrays the masses as victims or enablers, some of the best satire takes a look at society to subtly tell a bigger, harsher truth about the reality of power.

The prominent Pakistani cartoonist Sabir Nazar recognizes that every country has its own set of problems, but that they aren’t necessarily unique. For Nazar, that reality offers another way to satirically shed light on hidden truths: drawing international parallels. Directly comparing the situation in one country to that in another allows audiences to look at their circumstances with new eyes.

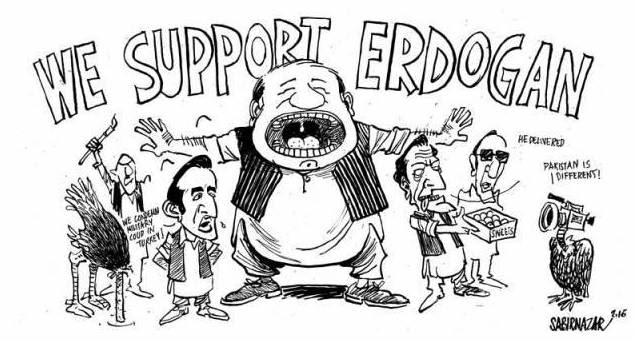

After the failed Turkish coup attempt in 2016, Nazar depicted Pakistani politicians and citizens condemning the event and expressing their support for Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (see Image 1 below). But Nazar observed that many in Pakistan would have actually welcomed the kind of military rule at home that had failed in Turkey (see Image 2 below).

He wanted to point out a hypocrisy he saw among many Pakistanis when it comes to military rule: they realize martial law isn’t an acceptable form of government elsewhere, yet still prefer it for their own country.

“If I was making cartoons in the U.S.,” Nazar says, “I would draw these international parallels.”

It’s a strategy that has met with some success in the U.S. “I think John Oliver does a great job when he talks about American politics because he relates it back to other countries,” says American writer Caitlin Kunkel, co-founder of The Belladonna and co-creator of The Satire and Humor Festival. Oliver, for instance, compared Trump to Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 during the Brazilian election. During the 2015 GOP primaries, Trevor Noah compared candidate Trump to African dictators. “For me as an African, there’s just something familiar about Trump that makes me feel at home,” Noah joked.

Both segments helped American audiences better understand their own politics, and forced them to reckon with its failings.“That was something that made people be like, ‘Oh, yes, that thing where we say we’ll never be like that, we’re actually getting a little closer to that,’” says Kunkel. More work like this would be a welcome, refreshing addition to American satire.

Down in South America, the intertwined satirical traditions of Chile and Argentina are further testaments to the effectiveness of skewering the conditions that give rise to political leaders.

In both cases, as with Pakistan, political turmoil is a key throughline. Both countries went through military dictatorships during the 1970s. Augusto Pinochet’s overthrow of Chilean president Salvador Allende in 1973 and Jorge Videla’s deposal of Argentine president Isabel Perón in 1976 marked the beginning of a dark era in terms of human rights and freedom of speech. Pinochet’s regime lasted for 17 years and Videla’s lasted seven, leaving behind strong feelings of resentment and polarization that linger today.

The transitions (back) to democracy haven’t been seamless. Argentina has faced a number of debt crises, the most famous of which saw five presidents come and go in just 11 days in 2001. Chile, meanwhile, is currently going through a period of serious social discontent rooted in decades of corruption and political inefficiency.

These common historical lines and sociopolitical problems have paved the way for a common satirical style, focused in large part on skewering society. Instead of throwing daggers at politicians, being able to point and laugh at themselves (and their broader communities) has become a key for many satirists and comedians.

One clear example of this is the Argentine comedian and YouTuber Guille Aquino, who produces sketches about the country’s constantly evolving social, political, and economic situation, as seen from the lives of regular people.

Aquino’s sketches illustrate common, everyday situations that take bizarre, unexpected turns. Be it climate change, fake news, drug use and regulation, or local policies on garbage management, Aquino’s comedy involves real people and society, rather than political leaders. He laughs about people’s hypocrisy, racism, and lack of tolerance. He makes his audience understand that the problems they usually associate with the political class are also present in themselves.

In his sketch titled “Urban Violence,” for instance, Aquino and a taxi driver exchange insults after a near collision. When the comedian tries to deescalate the situation, the driver stops him and says, “What are you doing? You’re breaking the protocol.” To Aquino’s disbelief, the man explains: “This is urban violence, man. This country is going to hell. You have your issues, I have mine, and we solve them by punching each other in the street. That’s how it works, right?” The point Aquino makes is clear: ordinary Argentinians live in a constant state of instability, frustration, and violence.

But perhaps the most prominent feature of modern South American satire is its aggressiveness. Comedians have left behind highbrow, mannered approaches in favor of low blows, nasty images, and offensive messages. It seems the tradition of smart irony and creativity that has defined the form has lost priority to being as harsh as possible.

Baby Etchecopar, a popular far-right monologist in Argentina, has called Nicolás Maduro, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevara “sons of bitches” and “pieces of shit.” Meanwhile, satirical media publications like The Clinic in Chile have used aggressive and graphic imagery of ministers, presidents, and political candidates on their covers. Surely these are some of the most extreme cases, but neither Etchecopar nor The Clinic are underground or niche voices. On the contrary, they have large audiences numbering in the tens of thousands, and their commentaries usually resonate heavily on social media.

“These new parameters for what is acceptable in humor have a clear origin in the recent history of dictatorships that we had to endure,” says Mariano Ramos, a cartoonist and screenwriter with more than 20 years of experience making comedy in both Argentina and Chile. “The fear and silence that reigned during the 1970s and 1980s were so strong that once the regimes were over, we just wanted to have fun and do whatever we wanted. We had been with a military boot on our heads for years.”

Ramos points out that the shift toward a stronger, more aggressive voice was gradual and borne out of a mix of intentional efforts and coincidences. On the latter, he remembers an anecdote: “During the Menem presidency, in the early 90s, I drew an extremely pornographic cartoon that got published in the youth newspaper of the leftist Partido Intransigente. Some days later, in one high school in Buenos Aires, a teenager got some homework about political parties, and in his research, he found the publication with my drawing in it. The kid brought the cartoon to school for his presentation, which resulted in him being expelled from the institution.”

“That small event triggered a discussion on a national level about where the limits were, and what things we were and weren’t able to say in this new era,” he explains. The incident shows how a single piece of satire can move the sociopolitical agenda to new places. Evidently, some of the lasting scars of the dictatorships were fear and censorship dressed up as politeness and correctness. But pushing those boundaries through comedy allowed society to speak up again.

America’s current situation, while still far from any kind of authoritarian regime, might find this case useful: how a renewed sense of freedom of speech can lead to more shamelessness and frankness in political humor, and how that kind of humor can push for change.

In the U.S., few subjects are off-limits and insult comedy is an established form, so taking an aggressive approach is certainly accepted. That said, abusing politicians can get you into trouble. For instance, after Kathy Griffin posted a photo of herself holding up a Donald Trump mask made to look like a severed head, she was essentially blacklisted from Hollywood. Similarly, Samantha Bee came under fire and was forced to apologize for calling Ivanka Trump “a feckless c***.” Even cartoonist Michael de Adder was fired from a Canadian publication for drawing a graphic caricature of Trump golfing near the dead bodies of migrants. The piece made a strong statement about American immigration practices, which was the point, but a cartoonist in another country had to pay the price for it because many in the U.S. felt it crossed a line.

But aggressive satire not only forces the audience to face harsh realities; it also incites an emotional response and challenges the powerful. As Kunkel puts it, “I hate the civility argument. I think only people in power tell other people to be civil. Obviously I don’t want to incite violence, but there comes a point where it’s like, if someone’s doing terrible things and is a huge hypocrite, to protect their image is [dumb]. You have to go past that.”

In the age of Trump, avoiding satire about the president is impossible. As the leader of the free world, he warrants coverage, and his personality and actions provide worthy material to comedians. But the amount of satirical attention being paid to Trump feels skewed. If the aim of satirists, as Ramos suggests, is to “take a stand, listen, and work to help their fellow citizens understand the times they are living in,” then repeatedly fixating on the same tired jokes about Trump isn’t going to do the trick.

The satirical landscapes in our home countries, focused less on leaders and more on the conditions that give rise to them, offer a glimpse of what American satirists might try more of. After all, the targets of Pakistani, Chilean, and Argentinian satire — polarization, inequality, hypocrisy, disillusionment — are not unique to those countries; they exist in their own ways in the U.S. too. A more society-focused approach to satire might force Americans to look inward and reckon with Trump not as a cause, but a symptom of problems of their own making.

Asked about the future of satire in the Trump era, Kunkel expresses cautious optimism. “I don’t think it’s impossible” to create good work, she says. Satirists can confront Trump. “But you often can’t come at it straight on or just do an impression,” Kunkel continues. “You have to critique the people around him, elements of the administration. You have to find more creative ways to pull apart what’s going on. Because it’s not just him, right?”

KEEP THE CONVERSATION GOING: What foreign country or satirist do you think American satirists can learn the most from? Let us know in the comments.

Not satire but a kick in the ass from the home folks:

"We Kentuckians know that our word is our bond. Oaths are the most solemn of promises, and their breach results in serious reputational — and sometimes legal — consequences.

President Donald Trump will soon be on trial in the Senate on grounds that he breached one oath. Senate Leader Mitch McConnell is about to breach two."

Satire doesn’t have a Trump problem (Bush wasn’t funny either, how quickly people forget), the world has satire problem:

When reality becomes too ridiculous to believe, satirizing reality becomes difficult if not impossible.

We do satire here on TPM. Very well, I might add.

W/r/t Trump…to some degree he is “immune”. But I have always believed that Trump derives his “immunity” from a comprehensive and thorough army of enablers…

dozens and dozens of lawyers and $$$$$$$$$ to buy them and a lot more

The BothSider elements of the Fourth Estate

People like American and foreign oligarchs

FOX

The RWNJ judges

SCOTUS

The GOP Senate

The GOP voters

Propaganda outlets too numerous to mention here

Barr’s control of the DOJ

A voter-plan to render Democratic votes useless

A Democratic electorate 50% of which is still unaware of the danger to the country and the world itself the dangers Trump presents

And much much MUCH more

Trump’s lizard-brain is not driving this, any more than insane tyrants through the years have “ruled-by-their-wits”. It’s the social organization that counts.

If Trump did not have these things, he would have been removed from Office years ago and would have been the subject of pity, not satire.

To satirize a man a criminal and evil as Trump is not a task I would want to do for a living:

ETTD works in the comedic world as well