As if the situation in the Gulf wasn’t bad enough already, we are now in hurricane season, and that means there’s a decent chance that a tropical cyclone may complicate the cleanup efforts along the southern U.S. coast and disrupt effort to bring the blowout at the site of the sunken Deepwater Horizon under control.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, there are an average of 2.9 named storms and 1.4 hurricanes in the gulf each hurricane season; and 1.4 named storms and 0.5 hurricanes by the end of August. During a heavy season, as 2010 is expected to be, there can be many, many more. And historically, the site of the Deepwater Horizon well has been right in the heart of a hurricane corridor.

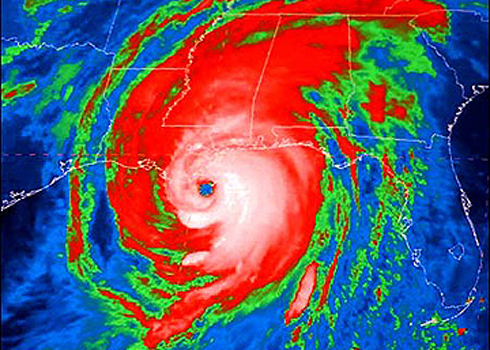

(This image, courtesy of NOAA, maps all tropical storms and hurricanes of the past 100 years that passed near the site of the spill, signified by the red star in the center.)

“You have to hire as many supertankers as you can find and pump as much of [the oil] into them before hurricane season. Once the hurricane’s come, the game is over. You can take a big tar mop and paint the Gulf Coast black.” That was the dim view of a Houston-based investment bank founder, and energy expert, as quoted in the Washington Post. Hurricane season, he said, would disperse the oil in the gulf and wash some of it on to the Gulf shore, drastically complicating clean up efforts. And sadly he may be right.

So what happens if a big storm hits?

“There’s a bunch of impacts,” says William Drennan, a hurricane expert at the University of Miami’s Rosentiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

“If you get a storm which is coming toward the coast you can get a significant storm surge,” Drennan told me in an interview Thursday afternoon. “If you get a storm surge, then the top meter of the water is going to go…certainly hundreds of feet possibly miles inland.”

That, he said, could propel oil “deep into the marshland,” where the ecological impact could be worse than if the oil remained on the surface or slightly below.

“The ideal situation would be to keep it away from land,” Drennan says. “If it could be kept away from lands, the wet lands tend to be very good hatcheries of everything from fish to birds…. Once you go the oil deep into the wetlands it’ll take a long time before it gets flushed back.”

Similarly, Drennan said, a big storm will cause mixing in the ocean, drawing oil from the water column below back up to the surface, where it can again be flushed ashore.

All of this is to say nothing of the impact on the ongoing efforts to cap the gushing well. Not only would work crews have to be brought in to port to wait out the storm, but the storm could damage the rigs being used to drill the two relief wells.

“They’d have to shut down completely the process of drilling,” Drennan says. “If it were to damage the rig which is drilling the two relief wells, if it were to damage those rigs–that would be an issue.”

All of this, he says, is something that the government and other agents in charge of the rescue effort “should be quite worried about.”

And they are. NOAA was quick to release talking points about the potential impact of a hurricane on the oil spill, which reinforce much of what Drennan told me, but also seek to downplay the risk, and don’t touch on the more pragmatic consequences a 400-mile wide storm would have on rescue and cleanup. By the same token, the fact sheet highlights some of the salutary effects a hurricane could have on the spill. “The high winds and seas will mix and ‘weather’ the oil which can help accelerate the biodegradation process,” reads one bullet point.

Additionally, NOAA advises, “A hurricane passing to the west of the oil slick could drive oil to the coast. A hurricane passing to the east of the slick could drive the oil away from the coast.”

What you won’t find, however, is anybody saying that a big tropical storm or hurricane will make things easier.