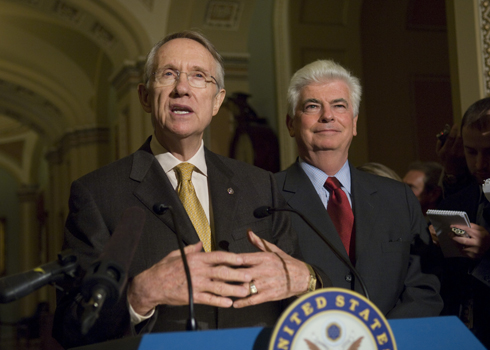

It’s done. The Senate this afternoon, by a vote of 60-39 passed the final version of Wall Street reform legislation — the exact same version the House passed two weeks ago, which will now go the White House for a signature. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) said that the President plans to sign the bill next week.

The development, though expected for days, represents a major achievement for President Obama and congressional Democrats — their first landmark bill since health care. And this time it’s actually popular.

But getting here wasn’t easy for Democrats.

Indeed, Democrats on the Hill and in the Obama administration are divided as to whether the legislation truly achieves the underlying objective of preventing future financial industry bailouts. That schism is personified by Sen. Russ Feingold (D-WI) — the only senator who voted against the bill from the left — who has argued that, to be effective, the Wall Street reform bill would have had to shrink big financial companies, break them apart or make other structural changes to the industry.

Though he was alone among Senate Democrats in voting no, his view is not an uncommon one.

Feingold’s defection came at a cost. Because they needed 60 votes to overcome a filibuster of the conference report, Democrats had to pursue the votes of three Republican moderates: Sens. Olympia Snowe (R-ME), Susan Collins (R-ME) and, especially, Scott Brown (R-MA).

As the 60th vote, Brown harnessed his extraordinary leverage in the final stages of the legislative process, and used it to demand carve-outs for major Massachusetts financial firms and delay final passage of the bill by weeks. Before the July 4th recess, Democrats were forced to take the unusual step of reconvening their financial reform conference committee to remove a bank tax, after Brown and Collins threatened to pull their support. (That tax was replaced with new revenue raisers, including one that brings the 2008 bailout bill to an early end.)

The yearlong debate over reform was marked, as so many initiatives have been, by ultimately ineffective stabs at bipartisan cooperation, which gave way after months to the Democrats’ ultimate strategy of plucking off enough moderate Republicans to pass the bill.

Despite the internal dissent among Democrats, the bill accomplishes some of the party’s biggest reform goals. It creates a resolution authority for the federal government to ease failed firms through the liquidation process — an authority former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson says would have helped him and the country a great deal during the financial crisis of 2008.

It will force big firms to move their risky derivatives-trading businesses into external affiliates where they’ll receive no federal protections — a provision authored during primary season by conservative Democrat Blanche Lincoln, and preserved in large part because her primary challenger, Arkansas Lieutenant Governor Bill Halter, gave her a run for her money and forced her to tack left.

It creates a new consumer financial protection bureau, housed inside the Federal Reserve, which will regulate financial products and protect consumers from predatory financial practices. It ends — or will soon end — major conflicts of interest on Wall Street, and strictly limits the extent to which big banks can make risky trades with their profits. And, in a huge coup for progressive and conservative populists, it allows a thorough audit of the Federal Reserve’s non-monetary policy operations, including the actions it took during the dark days of the crisis.

Next week’s signing ceremony will largely round out President Obama’s legislative agenda. But it will also mark a turning point in his presidency, after which major initiatives like health care and Wall Street reform will become much more difficult, if not impossible, to enact.