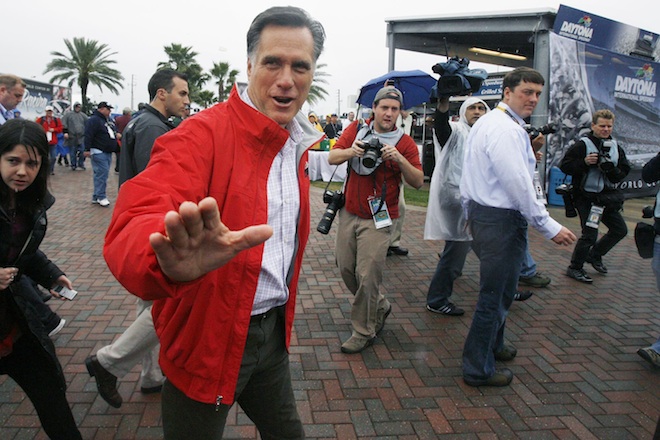

Pandering to the locals is a time-honored tradition in politics. Cave politicians probably got misty-eyed over how the village rocks were the right size. Mitt Romney, respectful of this practice, has done his best to win over primary voters by invoking a personal connection to various states. But many of the stories and anecdotes Romney tells to endear him to local constituencies often fall flat — or worse, earn him mockery on the national stage.

On Wednesday, Romney led off a conference call with Wisconsin voters by saying he has “a few connections with the state.” He offered up as an example a “humorous” memory from his childhood in neighboring Michigan — but his story centered on a factory closure ordered by his auto executive father, who then tried to keep the mass layoffs from wrecking his gubernatorial election.

Not exactly the most relatable tale outside the narrow subset of “children of CEOs-turned-governors.” Democrats quickly pounced on the remarks in order to further their preferred narrative, that Romney is wildly out of touch.

Unaligned Wisconsin GOP strategist Mark Gaul thought the whole thing was blown out of proportion by the national press outside the state: “It’s silly. It shouldn’t even be an issue.”

But it’s not the first time Romney’s personal anecdotes have gone awry. In Michigan, he played up his roots as a “son of Detroit,” but generated widespread ridicule with his musings about how “the trees are the right height.”

Romney also once tried to show his love for Detroit automobiles by noting how his wife owns two Cadillacs, another rich-guy reminder that even Romney admitted undercut his message. He described a nostalgic childhood memory about watching his father lead a parade in honor of the 50th anniversary of the American automobile. Only problem: The parade happened nine months before he was born.

Romney’s local touch worked better, for the most part, in New Hampshire, where he owns a home and handily won the state’s primary. It may be for the best that it came earlier in the primary calendar in Michigan, since Romney ended up running an ad about his ties to the state with major similarities to one he recorded about his ties to New Hampshire.

In Alabama and Mississippi, Romney claimed no historic connection like he did with Michigan, New Hampshire or Wisconsin, but local Republicans did a face-palm when he tried to court voters with a newly Southern persona. Romney lost both states badly.

“I’m learning to say ‘y’all’ and I like grits,” he said at one rally. “Strange things are happening to me.”

Southern Republicans made no secret of their disdain for Romney’s style. Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, who voted for Rick Santorum, told the AP a more honest approach would be to say, “I don’t talk like you, but I would appreciate your vote.” Even one of Romney’s backers in the state, former state GOP executive director Chris Brown, was offended. “Does he think we’re all rednecks?” he told the Boston Herald.

Among Romney’s other attempts to woo the locals: He has often recited “America the Beautiful” on the trail, emphasizing about the “amber waves of grain” in corn-heavy Iowa, the “purple mountain majesty” in rocky New Hampshire and the “spacious skies” in Florida’s space coast.

Romney is by no means the only one who’s stumbled trying to relate to local voters. Michele Bachmann was a walking cautionary tale, playing up her roots in Iowa only to mix up John Wayne’s birthplace with a town where serial killer John Wayne Gacy once lived. She also told a New Hampshire audience she admired them because the first shots of the American Revolution were fired in Concord and Lexington, which are actually in Massachusetts. Herman Cain asked Floridians at a Miami restaurant “How do you say delicious in Cuban?” which, truth be told, may not bad as bad as a 2007 pander gone wrong by Romney in which he accidentally repeated a Fidel Castro slogan in a speech.