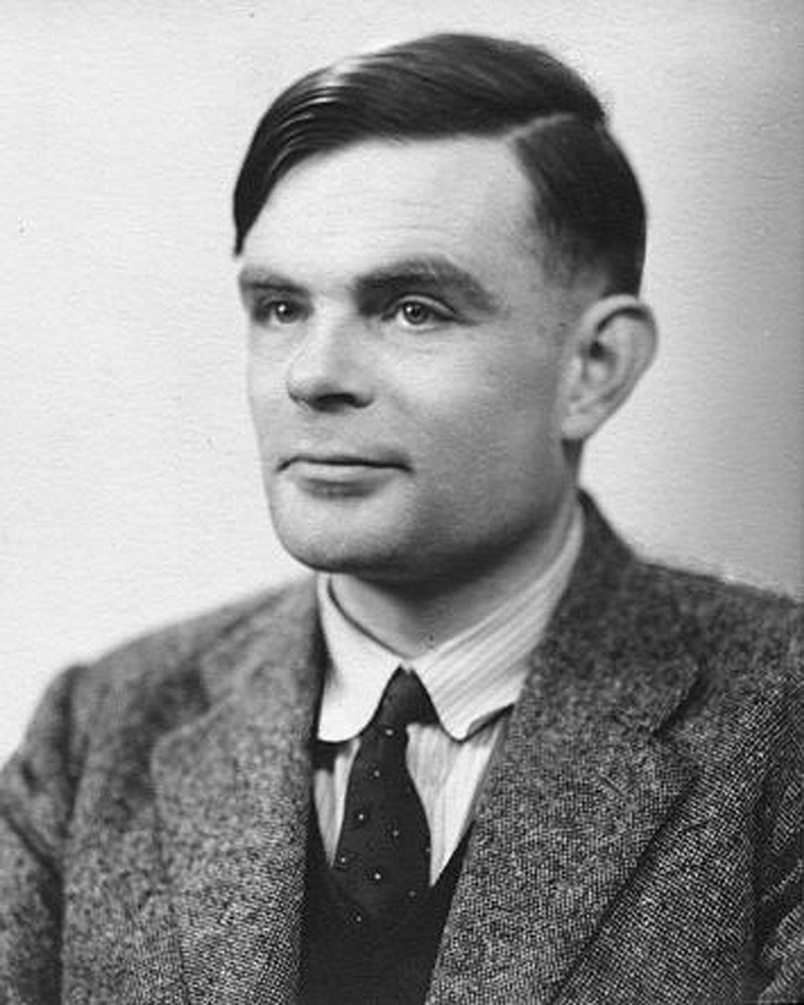

LONDON (AP) — His code breaking prowess helped the Allies outfox the Nazis, his theories laid the foundation for the computer age, and his work on artificial intelligence still informs the debate over whether machines can think.

But Alan Turing was gay, and 1950s Britain punished the mathematician’s sexuality with a criminal conviction, intrusive surveillance and hormone treatment meant to extinguish his sex drive.

Now, nearly half a century after the war hero’s suicide, Queen Elizabeth II has finally granted Turing a pardon.

“Turing was an exceptional man with a brilliant mind,” Justice Secretary Chris Grayling said in a prepared statement released Tuesday. Describing Turing’s treatment as unjust, Grayling said the code breaker “deserves to be remembered and recognized for his fantastic contribution to the war effort and his legacy to science.”

The pardon has been a long time coming.

Turing’s contributions to science spanned several disciplines, but he’s perhaps best remembered as the architect of the effort to crack the Enigma code, the cypher used by Nazi Germany to secure its military communications.Turing’s groundbreaking work — combined with the effort of cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park near Oxford and the capture of several Nazi code books — gave the Allies the edge across half the globe, helping them defeat the Italians in the Mediterranean, beat back the Germans in Africa and escape enemy submarines in the Atlantic.

“It could be argued and it has been argued that he shortened the war, and that possibly without him the Allies might not have won the war,” said David Leavitt, the author of a book on Turing’s life and work. “That’s highly speculative, but I don’t think his contribution can be underestimated. It was immense.”

Even before the war, Turing was formulating ideas that would underpin modern computing, ideas which matured into a fascination with artificial intelligence and the notion that machines would someday challenge the minds of man. When the war ended, Turing went to work programing some of the world’s first computers, drawing up — among other things — one of the earliest chess games.

Turing made no secret of his sexuality, and being gay could easily lead to prosecution in post-war Britain. In 1952, Turing was convicted of “gross indecency” over his relationship with another man, and he was stripped of his security clearance, subjected to monitoring by British authorities, and forced to take estrogen to neutralize his sex drive — a process described by some as chemical castration.

S. Barry Cooper, a University of Leeds mathematician who has written about Turing’s work, said future generations would struggle to understand the code breaker’s treatment.

“You take one of your greatest scientists, and you invade his body with hormones,” he said in a telephone interview. “It was a national failure.”

Depressed and angry, Turing committed suicide in 1954.

Turing’s legacy was long obscured by secrecy — “Even his mother wasn’t allowed to know what he’d done,” Cooper said. But as his contribution to the war effort was gradually declassified, and personal computers began to deliver on Turing’s promise of “universal machines,” the injustice of his conviction became ever more glaring. Then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued an apology for Turing’s treatment in 2009, but campaigners kept pressing for a formal pardon.

One of them, British lawmaker Iain Stewart, told The Associated Press he was delighted with the news that one had finally been granted.

“He helped preserve our liberty,” Steward said in a telephone interview. “We owed it to him in recognition of what he did for the country — and indeed the free world — that his name should be cleared.”