NEW YORK (AP) — In the aftermath of last month’s terror attacks in Paris, New York City officials have bolstered security and quietly stepped up outreach efforts to Muslim residents, trying to calm fears of possible hate-filled retaliation while trying to extend government services to a community that often has felt neglected.

The city has increased its presence in Muslim neighborhoods, sending staffers to visit mosques and build better relationships with imams and worshippers. Police officials have briefed community leaders on new counterterrorism procedures. Other city officials have urged Muslims to report any hate crimes, the number of which — despite terror-filled headlines and the inflammatory rhetoric of some national politicians — is sharply lower in New York in 2015 than at this time a year ago.

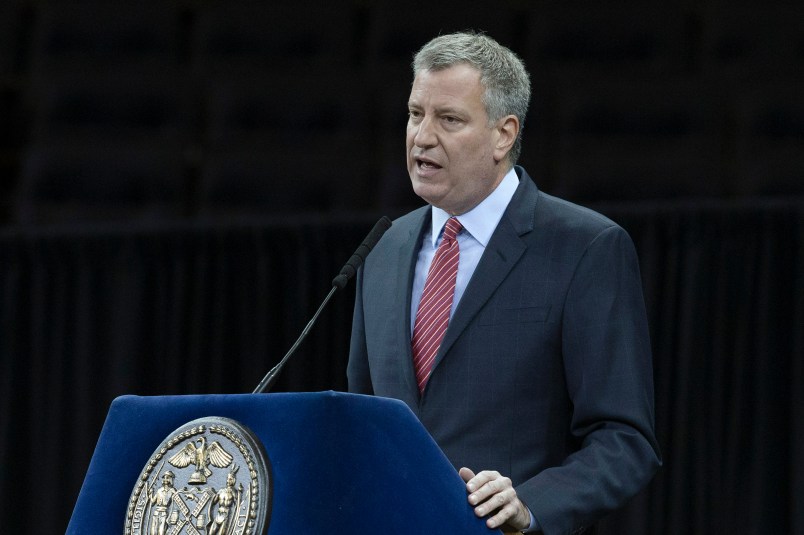

Mayor Bill de Blasio on Friday is to deliver a speech at an Islamic community center, reaffirming that the city’s 800,000 Muslims have the same rights as all New Yorkers while pledging protection from any hate crimes, the mayor’s aides told The Associated Press on Thursday.

De Blasio’s speech at the Jamaica Muslim Center, or Masjid Al-Mamoor in Queens, is the most high-profile move the administration has made to calm jittery Muslims since the Nov. 13 attacks that killed at least 129 people in Paris, and this week’s slaying of 14 people in San Bernardino, California. But it’s far from the only step the administration has taken to reach out to Muslims, some of whom deeply feared discrimination after 9/11.

Six days after the Paris attacks, the Mayor’s Community Affairs Unit organized a meeting between 40 community leaders — the vast majority from the Muslim community — and the NYPD’s Hate Crimes Unit with aims of building the trust necessary for Muslims to turn to law enforcement to report crimes.

Teams from the mayor’s office and city council have spent time at mosques and community centers, hoping to improve relations with imams who could also advocate city services, such as free pre-kindergarten and municipal identification cards, that would improve some Muslims’ level of civic engagement and potentially ward off alienation.

“This is a community that has not always had the best relationship with city government,” said Marco Carrion, head of the mayor’s community affairs unit. “Some have never seen a helpful government and welcomed us with open arms. But other times we face real resistance and mistrust.”

NYPD officials said there has not been an uptick in bias crimes against Muslims since the Paris attacks. So far this year, there have been 14 hate crimes against Muslims, a 39 percent decrease from this time a year ago, according to NYPD statistics. But officials acknowledge that some hate crimes go unreported.

The NYPD, which has 900 Muslim officers, uses its Community Affairs Bureau to foster better relationships with all of the city’s diverse communities by staffing street festivals, providing services to accident victims and trying “to make people who don’t normally talk to cops feel comfortable coming to us,” said the head of the unit, Chief Joanne Jaffe.

This summer, the unit circulated fliers offering support to Muslim-owned shops in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

After the Paris attacks, the NYPD increased security at mosques, as well as synagogues, and reached out to more than 40 Muslim organizations. On Monday, Police Commissioner William Bratton will host a conference for clergy members focusing on community involvement and the NYPD’s counterterrorism threat assessment program.

“Outreach by the city to the Muslim community is critically important, especially now,” said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union. “But there must be clear distinctions between the outreach and anti-terrorism efforts. Otherwise, it will discourage Muslims from going to law enforcement and just breed further distrust.”

After September 11, the NYPD used its intelligence division to detect terror threats by cultivating informants and conducting surveillance in Muslim communities. Over the years, the practice resulted in a handful of prosecutions of homegrown terrorists and, more recently, became the subject of a series of articles by The Associated Press revealing that the intelligence division had infiltrated dozens of mosques and Muslim student groups and investigated hundreds.

Last year, amid complaints of religious and racial profiling, the NYPD disbanded a team of detectives assigned to create databases but has continued its use of informants and undercover investigators to fight terror.

Some Muslims say they have felt harsh stares in recent weeks.

“I don’t like the idea that regular everyday Muslims are being lumped together with terrorists,” said Maryam Mohiuddin, a hijab-wearing American artist from Bangladesh who was visiting the Al Farooq Mosque in Brooklyn. “I’d like it better if people don’t look at me with suspicion. I’d rather them ask me questions.”

___

Associated Press writers Tom Hays and Rachelle Blidner contributed to this report.

___

Contact Lemire on Twitter @JonLemire

Copyright 2015 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Terrier sympathizers!