AUSTIN, Texas (AP) — Texas Gov. Rick Perry has spent a record 14 years in office vanquishing nearly all who dared confront him: political rivals, moms against mandatory vaccines for sixth graders, a coyote in the wrong place at the wrong time.

But with eight months left on the job and a decision to make about the 2016 presidential race, the long-serving governor known for his Texas swagger is now the focus of a grand jury investigation that could cause more difficulty than any adversary has.

What should have been a political victory lap for Perry could now wind up in a final tussle that has implications for his political future.

“Gov. Perry is used to being challenged every step of the way in almost every issue. In that sense, this is not significantly different,” said Ray Sullivan, Perry’s onetime chief of staff and a former spokesman. “This just comes with the territory.”

A judge seated a grand jury in Austin this week to consider whether Perry, who is weighing another run for the White House, abused his power when he carried out a threat to veto $7.5 million in state funding for public corruption prosecutors last summer.

Aides to Perry say he legally exercised his veto power. Others say Perry was abusing his state office and is finally getting his comeuppance.

The state Public Integrity Unit operates under Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg, a Democrat who has been the subject of Republican grumbling that the office investigates through a partisan lens. Lehmberg, who took office in 2009, was convicted of drunken-driving last year and filmed in a jailhouse video berating officers following her arrest.

Perry called on Lehmberg to resign and torpedoed the funding when she didn’t.

Craig McDonald, whose public watchdog group filed a complaint that a Texas judge took seriously enough to hire a special prosecutor, said the veto embodied a brash governor who’s gotten too accustomed to dictating to others.

“He threatened her in broad daylight just like it was high noon,” said McDonald, the executive director of Texans for Public Justice. “I think it’s indicative of perhaps someone in the office a little too long.”

Lehmberg, who served about half of a 45-day jail sentence, has called Perry’s attempts to remove her partisan. The public corruption unit, which prosecuted former Republican U.S. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay in 2010 on charges of laundering campaign funds, now runs on a smaller budget with local taxpayer funds and a scaled-back staff.

Special Prosecutor Michael McCrum has said he has specific concerns about the governor’s conduct but refused to elaborate. Perry’s office has hired a high-profile defense attorney, David Botsford of Austin, who is being paid $450 hourly and with public funds.

The grand jury is impaneled for three months. In the original complaint, McDonald accused Perry of breaking laws related to coercion of a public servant and abuse of official capacity.

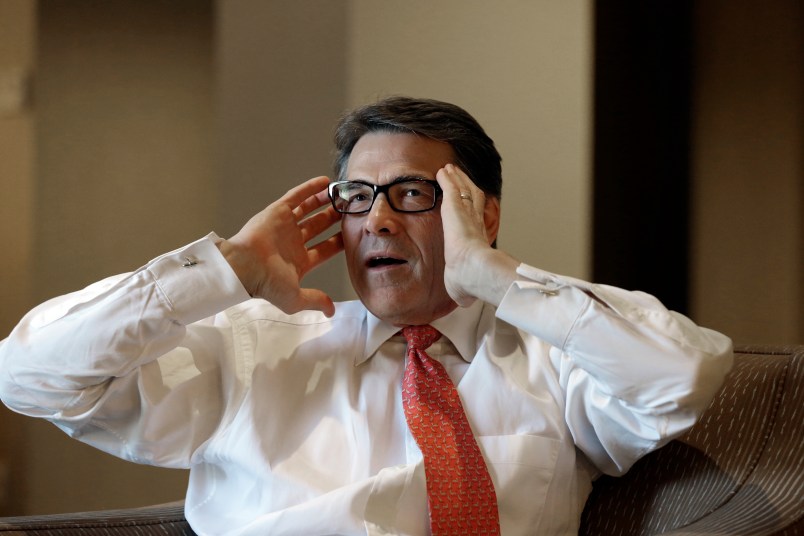

Perry never lost an election until his run for the Republican presidential nomination flamed out in 2012. If he makes another bid upon leaving office in January, he’s positioned to boast of an even more robust Texas economy and to project a slightly toned down image: he now wears a pair of thick-framed glasses and seldom slides on his cowboy boots anymore.

But the grand jury probe could draw attention back to more contentious issues, even if Perry is not indicted. And if the panel does pursue charges, “that would be very, very hard to overcome, particularly because voters already have a perception of him in their mind, and right now he’s been busy cleaning that perception up,” said Ford O’Connell, a Republican strategist in Washington. “It would put him on life support as a presidential candidate.”

A Texas governor hasn’t been indicted since 1917. Democrat James E. Ferguson was eventually convicted on 10 charges, impeached and removed from office for vetoing funding for the University of Texas after objecting to some faculty members.

Some legal experts see the allegations against Perry as shaky.

“If the governor were to pressure someone to not prosecute someone, that would be some violation of some clear legal duty. Pressuring them to quit? That’s a little less clear,” said David Kwok, a law professor at the University of Houston.

___

Follow Paul J. Weber on Twitter: www.twitter.com/pauljweber

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.