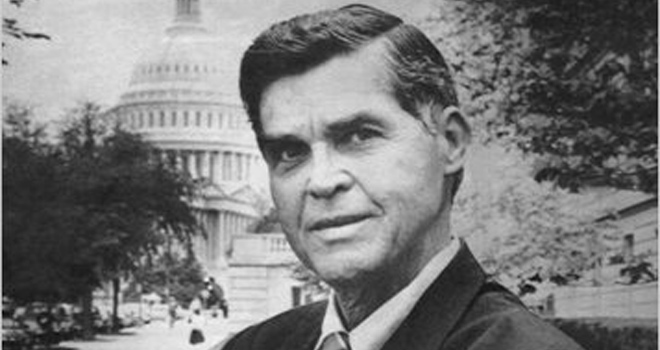

Ever wanted to know who to thank for House Speaker John Boehner’s congressional career? The late Ohio Republican Rep. Donald “Buz” Lukens was your man.

It was 1990. Lukens was in his second term in Congress. The year before, the 58-year-old congressman had been caught on a television network’s hidden camera in a McDonald’s restaurant speaking with the mother of a 16-year-old girl he was allegedly sleeping with.

Lukens was soon convicted of paying the teen $40 to have sex with him and wound up serving nine days in prison and paying a $500 fine. That would be his first of two stays in prison, and his second of three sex offense allegations.

Despite the scandal with the 16-year-old, Lukens ran for reelection. He declared his bid for reelection on May 2, 1990, calling the whole debacle a “dumb mistake.”

Boehner, who was at the time was president of a packaging sales company, saw his chance. He crushed Lukens in the Republican primary, launching the congressional career that has brought him to the position second in line to the presidency.

Now, thanks to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, TPM has obtained the agency’s 1,627-page file on Lukens. The file reveals more details about the various scandals of the congressman, who died last spring.

According to the FBI report, Lukens told his staffers that the underage girl had given him a fake I.D. that said she was 20 years old. The staffer said Lukens maintained the attitude that there was nothing wrong with what he did. Lukens felt he could have won the election if he had come forward and apologized.

“10,000 people voted for a convicted sex offender,” one staffer told an FBI agent, referring to the 20 percent of the vote Lukens received in his race against Boehner.

His FBI file also notes a 1954 arrest for “investigation of molesting.” Lukens had just graduated and was working at Procter & Gamble when he allegedly went to an ex-girlfriend’s home while she wasn’t there. Her two small children were, however, and he was detained the next day. All charges were dropped eight hours later, after cops found “no case.”

While attempting to finish his term as representative, Lukens was accused of fondling a young House elevator operator. After the House Ethics Committee decided to pursue an investigation, he resigned from office with two months left in his term.

Lukens appears to have been hard pressed for money towards the end of his career in office. According to the report, when asked why the Congressman was having financial problems, an unnamed staffer replied that the talk around the office was that Lukens spent a great deal of money on prostitutes. The source stated that women would regularly call the office asking for Lukens. On one occasion, another staff member, took a call from a woman who stated she had been “waiting at the Madison Hotel for Congressman Lukens for 45 minutes.”

Another staffer suggested Lukens’ “generosity and/or ignorance might have contributed to his financial woes”; Lukens would buy rounds of drinks for lobbyists instead of having the lobbyists pay for his drinks, as the system usually works, says the report.

It was that apparent need for money that led to his relationship with Henry Whitesell and subsequent inclusion in his thoroughly tangled murder investigation that dominates the vast majority of Lukens’ FBI file.

Before he was found murdered with three bullet holes in his body, Whitesell and John P. Fitzpatrick co-owned a for-profit trade school in Ohio called Cambridge Technical Institute (CTI). According to the FBI file, the school administrators “stalked the poor, the homeless and the unstable,” at welfare centers and soup kitchens, paying enrollment “bounty hunters” cash bonuses for every new student they snared for CTI.

They made a killing — $1 million yearly salaries — by allegedly falsifying records and continuing to collect the government grants when the students, often emotionally addled and illiterate, dropped out.

It was when the school came under investigation by the Legal Aid Society and the Department of Education (DOE) in 1990 that the former congressman came up in the murder investigation. A cooperating witness on the case described Whitesell and Fitzpatrick as being chummy with Lukens. The pair often turned up in the congressman’s office, and were regularly greeted with VIP White House passes, the source said.

With the DOE audit looming, Fitzpatrick allegedly told Lukens to “Get the sons of bitches” — the DOE auditors — “off my back.” Whitesell paid him $7,500 in May of that year.

The congressmen reportedly warned Whitesell there wasn’t much he could do. Yet this was just weeks before the May 8, 1990 primary and it appears Lukens needed money for his campaign. Luken’s reelection bid consisted almost exclusively of a last-minute media blitz which, according to several sources, appeared to have been funded wholly by the four subsequent CTI bribes totalling $20,000. According to a staffer, Lukens was hoping his appeal for the sex offense conviction would come through before the primary. If the appeal was granted, he thought he could win reelection.

Whitesell was found dead in the phonebooth with potentially falsified student documents in the trunk of his car. The DOE audit had just ended, and there were rumors that Whitesell was involved in a drug deal to pay off his gambling debts.

Some pages later, however, the FBI recorded that Fitzpatrick was “known to carry a .45 caliber handgun and is considered to be a prime suspect in the unsolved murder of his partner, Henry Whitesell.” He was described as “5’5″, 150 pounds, allegedly wears a hairpiece.” Fitzpatrick was still hanging out with Lukens. Fitzpatrick pleaded guilty to conspiring to defraud the United States by impairing the lawful functions of the government in 1997. As of 1999, the Associated Press reported, the murder case remain unsolved.

Lukens’ long fall from grace oscillated from scandal to scandal. In November 1994, Rosie Coffman sued Lukens for $750,000 for paying her for sex as a teenager. The same year, a federal grand jury charged Lukens with taking a $5,500 bribe from an Ohio company to help it win an extension of a government construction contract. Though he wasn’t indicted and both the company and its president were exonerated in the trial, the F.B.I. file still reeked of suspicious activity.

Lukens received and cashed four checks from employees of Holk Development Inc., totaling $5,500 between 1989 and 1990. Investigations indicated the checks were written with the hopes that Lukens would be able to help Holk reclaim the enormous government contract it once held to refurbish Pentagon offices.

A witness in the case described “illicit non-campaign contribution payments” made to Ohio senator John Glenn and then-Congressmen Lukens. Holk also appeared to be running an “illegal gambling and loansharking” operation being conducted out of Holk’s contruction trailer at the Pentagon. Holk maintained and operated a yacht on the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., which was used to entertain U.S. military and government officials.

During the F.B.I. investigation, a Holk employee admitted to being instructed to pay a $11,000 bribe to a Pentagon official, and the Army Procurement Fraud division stated that Holk’s president showed up with two thugs “purporting to be Holk employees, in an obvious attempt to intimidate the Army’s contracting official.”

On Feburary 23, 1995, Lukens was arrested in Kent, Ohio, and indicted on five felony counts including bribery in the U.S. District Court for Washington, D.C.. That same day Fitzpatrick was taken into custody and was indicted on eight felony counts alleging bribery, conspiracy to defraud the United States, and giving false testimony before the grand jury.

Lukens tried, and failed, to appeal two of the charges in 1997. He served a two-year sentence in a low-security federal prison in Texas, while suffering from an advanced case of throat cancer.

Lukens moved to Dallas, where the Cincinnati Enquirer checked up on him some years later. A neighbor described him as “a sad old man who shuttered his windows whenever he goes out.” He never mentioned his former career in congress.

Lukens died on May 25, 2010, in a Texas nursing home. His New York Times obituary included this detail: in 1987, while Lukens was in his first year in the House, he “joined Representative Newt Gingrich and other congressmen to pay for a book lambasting the House titled The House of Ill Repute.”