There are only a few dozen Americans who have given at least $1 million to super PACs this election cycle, and Kareem Ahmed is one of them. If you manage to talk to him, he’ll tell you a lot. He’ll tell you all about a class of pharmaceuticals, called compound drugs, which he is in the business of promoting, and which have been the subject of a contentious debate in California, where he lives and works. He’ll tell you to read ProPublica’s reporting about Big Pharma. He’ll tell you House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi is his best friend. He’ll tell you about his dream to someday take the proceeds of his business and build the largest non-profit children’s hospital in the world in Southern California’s Inland Empire. He’ll tell you how he fixed Democratic political strategist Paul Begala’s leg. He’ll tell you how much he loves President Barack Obama, whom he has met on a number of occasions.

He told me several times that he thought I’d been hired by Republicans, insurance companies, or his competition to destroy him.

“I really want to educate you, Eric, I really do,” Ahmed said in an interview over the phone in late August. “Because, you know what, because I’m prepared. My law firms are ready to go, and I’ve got PR firms retained already. They’re waiting for your article.”

Why?

“Because the message I got from you, Eric, was, you have been hired by either the Republicans or by the competition, or somebody, just out to destroy me, without even knowing the facts,” he said. “So what would you do if you were in my shoes? So I’ve got the White House on notice. I’ve got everybody on notice. That all right, I can’t wait until this thing comes out, and we’re going to go after your publication, you, and whatever, and if there’s anything that’s defamatory, that’s not factual, oh yeah, I’m ready. We’re waiting. My employees are watching. My law firms are watching. I mean, they are watching you. Like, every move.”

Part of the reason Ahmed felt the way he did was, in early August, I showed up at his office uninvited. Numerous attempts to schedule an interview had been either ignored or rebuffed, and I had been told that Ahmed was booked solid for weeks. But I was hoping to meet a man who had never given a press interview, and who has quietly come out of nowhere to become one of President Obama’s biggest individual financial backers. The same man runs a company, Landmark Medical Management, which experts and officials in California say is among several that have made millions of dollars over the past few years by capitalizing on a peculiar and newly carved-out corner of the state’s workers’ compensation system. Issues related to the drugs supported by Ahmed have already prompted California lawmakers to pass one new law, and may yet inspire more legislative action. I had questions about these topics.

The day I showed up at Landmark Medical Management’s office, on the second floor of an unremarkable two-story office building in Ontario, Calif., Ahmed agreed only to a brief, off-the-record conversation in the presence of his lawyer. In that meeting, he asked that questions be sent to him in an email, so that he could draft written responses. A few days after that first meeting, I sent Ahmed an email with several dozen queries, most concerning the activities of at least six active companies tied to Ahmed that are registered to office suites in the same building as Landmark. I received no response to that email. A few weeks later, I followed up with a phone call, and found that Ahmed suddenly had lots to say.

“So what I’m saying, my friend, is, as long as it’s honest, it’s truthful, I have no problem,” he told me. “It doesn’t make a difference. But if it’s unfactual, it’s defamatory, you are trying to destroy me in cahoots with somebody else, then there’s going to be a problem.”

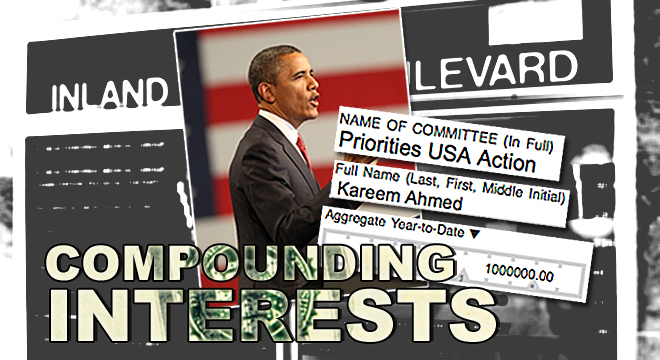

You’d be forgiven if you don’t recognize Ahmed’s name. Before this year, his political giving was limited to a few four-figure checks to California candidates. Several veteran California politics watchers contacted for this story had no idea who Ahmed was, either. But here’s the thing: so far in 2012, Ahmed’s contributions to Obama, Democrats, and the outside spending groups that support them have totaled more than $1.1 million. Ahmed’s wife, Tayyaba Farhat, has contributed another $75,000. At a time when Democrats were most worried about their ability to attract the big-dollar donors that made Republican outside spending groups such behemoths, Ahmed became a gift that kept on giving.

Ahmed’s big checks started coming in February. The first, on Feb. 6, was for $35,800 and made out to the Obama Victory Fund, a joint fundraising committee supporting both the Obama Campaign and the Democratic National Committee. Only a few weeks later, two $250,000 donations went to Priorities USA Action, the most prominent Democratic super PAC. In March, Ahmed sent Priorities another $500,000. In April, the Obama Victory Fund got another $40,000. In May, his wife gave the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee $30,800. In June, Ahmed gave $50,000 to House Majority PAC, a super PAC supporting Democratic efforts to retake the House of Representatives. Thousands of dollars from Ahmed and his wife have ended up in the campaign coffers of Democratic state parties and candidates across the country, including Sen. Bill Nelson in Florida, Senate candidate Tim Kaine in Virginia, and Rep. Brad Sherman in California.

Ahmed’s donations have allowed him to rub shoulders with many of the most powerful people in the country. He has been to high-priced fundraisers and events with Obama and the First Lady, including a headline-grabbing May 10 dinner with the President at the California home of the actor George Clooney.

“I hang out with governors, U.S. Senators, Nancy Pelosi is a personal friend,” Ahmed said. “OK, listen, a lot of people are my personal friends.”

White House records show that a Kareem Ahmed met with White House officials as part of large groups of visitors on separate occasions in March and April, one with Ari Matusiak, director of Private Sector Engagement and executive director of the White House Business Council, and one with Victoria McCullough, a staff assistant with the Office of Public Engagement. It is unclear if it is the same Kareem Ahmed.

Ahmed’s donations to Priorities alone put him in elite company. According to figures maintained by the Center for Responsive Politics, only 55 individuals and married couples have given $1 million or more to super PACs this cycle. (Super PACs can accept unlimited donations but must disclose their donors, while donors to 501(c)4 organizations, so called “social-welfare” groups, remain completely anonymous.) As this article was going to publication, Ahmed ranked 15th on the center’s list of the top donors to outside groups who generally support liberal candidates, placing him behind Democratic heavyweights like the investor James Simons and DreamWorks Animation CEO Jeffrey Katzenberg, and ahead of other notables, like the actor Morgan Freeman and former Loral Space and Communications Chairman Bernard Schwartz.

Priorities, run by former White House staff members, raised $10 million in August, its best fundraising month so far, and recent reports have touted how big Democratic donors are “finally” opening their wallets for super PACs. But back when Ahmed’s checks were coming in, Priorities was still dealing with headlines like this one, from Politico on March 20: “Pro-Obama super PAC struggles.” During the first three months of the year, Ahmed’s checks represented more than 20 percent of Priorities’ 2012 fundraising haul.

And yet, in the super PAC era, even a publicly disclosed seven-figure donor is able to get lost in the crowd. Ahmed provides perhaps the best example of how much can remain unknown about the individuals having the biggest financial impact on the political process. Even after embarking on a political spending spree, his public profile has remained virtually nonexistent.

Before this article, Ahmed’s only comments to the media came in the form of a short statement prepared in March, a document so boilerplate it reads as if it were written by a seasoned political pro.

“President Obama is fighting to help middle class families during tough economic times, to transition our nation to a clean energy future, to fight to keep improving our health care — the list goes on and on,” said the statement, first obtained by the website California Watch. “Priorities USA Action has the President’s back, and I’m proud to have theirs.”

In media reports on major donors to super PACs, Ahmed has been mentioned only in passing as the president and CEO of Landmark, described in multiple places as a “medical billing company.” That’s true enough, but it’s not the whole story.

Ahmed is middle-aged, with a round face, thinning black hair, the vestige of an accent, and a flair for hyperbole. His office is utilitarian — he sits at a wooden desk, with numerous computer screens arranged in a grid beside him — but his business card, with Landmark’s “LMM” logo featured in silver letters, is cut from extra-thick, dark blue paper stock. During our conversations, his tone shifted often from conviviality to aggression to supplication and back again.

Over the phone in August, he talked about coming from a family of doctors, and also of once working at a Jack in the Box. He described himself as a “small guy” fighting the influence and power of the major pharmaceutical companies. He also gabbed about spending time with big shots like DreamWorks’ Jeffrey Katzenberg, the director Steven Spielberg, and the Democratic political operative Paul Begala at a function in Beverly Hills, and arranging for Begala to treat a leg injury with compound drugs. (Begala confirmed the gist of Ahmed’s story in an email, and said that the treatment “seemed to help.”) Â Â

After spending more than two decades in workers’ compensation-related fields — “small stuff,” Ahmed called it — he hit upon the idea for Landmark Medical Management, which was formed in 2007, and which has quickly grown to 180 employees. Landmark occupies a suite in a building called The Inland Atrium in Ontario, a sprawling city of subdivisions, office parks, mini-malls, and chain restaurants an hour’s drive east of Los Angeles. Other tenants in The Inland Atrium include a law office, a physical therapy office, and a company called Pac-Bridge Merchandise, Inc. (When I visited, a Landmark employee told me the company soon planned to move to a different building in town.) In two years, Ahmed hopes to take Landmark public.

“And then I’ll be able to take on the pharmaceutical giants head on,” he said.

Landmark purchases account receivables from medical providers who prescribe compound topical analgesics — pain creams — to workers’ compensation patients, and makes its money by collecting from the insurance companies who owed on those accounts. The workers’ compensation system in California is so choked up with payment disputes that it can take months for a provider to be reimbursed by insurance companies for a service. The way Ahmed sees it, his company creates “liquidity” in the system by purchasing account receivables from doctors and getting them paid quicker. By his own account, he has also taken on a role promoting the medical practices he profits from.

Ahmed was reluctant to discuss the specifics of his business, particularly when it comes to the activities of his non-Landmark companies. There are at least six companies tied to Ahmed that are registered to various suites in the same building as Landmark: HNW Consulting Inc., Healthcare Finance Management LLC, Med-Rx Funding LLC, Physician Funding Solutions LLC, Pharmafinance LLC, and RX Funding Solutions LLC. The functions of these companies are unclear. All were formed since 2005, and not one currently has a website (neither does Landmark). Landmark is the only one of Ahmed’s companies that appears on the The Inland Atrium’s wall directory. A former Landmark executive suggested to me that several of the companies are used as holding companies for liability and tax reasons.

“My problem is, I don’t want competition,” Ahmed said. “I like to have a private life. I don’t want people to copy my business model, which I have wasted millions on, with legal opinion letters, from whatever, perfecting it over years. I don’t want people to take it for free, and start giving me competition. I’m a businessman, too. That is why I’m hesitant on answering all these things, because you’re going to expose my entire business model, and everyone’s going to say, ‘Oh, thank you, Mr. Lach, now let’s go compete, and give Mr. Ahmed and Landmark competition.’ I don’t want that.”

On the other hand, Ahmed told me that he would “love” me if my article could “get a point across that, why does everybody fight against compounds?”

“Forget about me for a moment, man,” Ahmed said. “You’re obligated, now that you know about it, and you’re a reporter, I think that you have every obligation in humanity to do that, to save millions of lives around the country. Let people know what compounding really is.”

At their most basic, compound drugs are those where ingredients have been combined, mixed, or altered by a pharmacist to meet the particular needs of an individual patient. If, for example, a patient is allergic to an ingredient in a commercially available drug, a pharmacist can compound a similar drug without the offending ingredient. According to the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists, an industry group that promotes the practice, compound drugs now make up between one and three percent of the nation’s $300 billion prescription drug market, and the practice occurs in some form in many pharmacies and hospitals. Compound drugs are not FDA-regulated. And pharmacies are not required to report adverse events associated with compound drugs to the federal agency. Instead, regulation of compound drugs falls to each state’s pharmacy board.

The compound drugs promoted by Ahmed are topical analgesics. Whereas the idea behind pharmacy compounding is to tailor drugs to a patient’s particular needs, Ahmed argues that creams are, in general, preferable to pills for treating pain, because creams avoid the side effects associated with orally taken opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (like ibuprofen), and other common pain drugs.

“I’m saving lives, by promoting compounds,” Ahmed said. “[I’m] telling doctors, ‘Look, why are you killing people with morphine and OxyContin and narcotics? Come on, go easy on the patients.'”

Ahmed, though not a doctor himself, said that he came to the conclusion that compounds save lives because there are “millions of studies” on the topic.

California’s Division of Workers’ Compensation guidelines, though, state that (PDF) topical analgesics are “largely experimental in use with few randomized trials to determine efficacy or safety.” The guidelines add that for many commonly compounded ingredients, there is “little to no research to support the use of many of these agents.”

The FDA, too, has raised concerns in the past about pharmacy compounding. In 2007, a consumer update from the agency titled “The Special Risks of Pharmacy Compounding” said the practice was coming under scrutiny. Asked for comment on topical analgesics, an FDA spokesperson pointed to the agency’s general guidelines concerning compound drugs, which state that while the FDA “will continue to defer to state authorities regarding less significant violations” related to compound drugs, the agency “believes that an increasing number of establishments with retail pharmacy licenses are engaged in manufacturing and distributing unapproved new drugs for human use in a manner that is clearly outside the bounds of traditional pharmacy practice.”

Meanwhile, people who know the workers’ compensation system best in California argue that compound drugs became popular only after a profit opportunity was identified.

“[Landmark is] just one of a big chunk of operations that find manipulable loopholes,” Mark Rakich, a staff member for the California Assembly Insurance Committee, said in an interview. “One could debate whether some of the arrangements violate existing provisions of law.”

Several years ago, the workers’ compensation system in California experienced a sharp increase in the amount of compound drugs, primarily topical analgesics, prescribed to injured workers. In 2010, the California Workers’ Compensation Institute, an insurance-industry-backed group, published a study (PDF) looking at the period between 2006 and 2009. The study found that over that period, the percentage of California workers’ compensation prescription dollars that paid for the drugs associated with compounding rose from 0.8 percent to 6.4 percent. The State Compensation Insurance Fund, a quasi-governmental body and a big player in the system, saw billings for a range of items that were rarely billed before 2007 — including compound drugs — reach $58 million in a 16-month period. It was during this period that Landmark was founded.

“Unfortunately, a certain percentage of physicians are actively willing to enter into clever arrangements with various kinds of service providers for things that are just more expensive than they need to be to effectively treat injured workers,” Rakich said.

Ahmed said that Landmark was not involved with some of the marked-up products associated with the compound drug surge in California that have been of most concern to officials. Still, he did acknowledge that compound pain creams, on the whole, are more expensive than more commonly-prescribed pain drugs.

“Yes, they’re expensive, of course, because you’re curing people, and it can’t be done on a mass scale, because the FDA does not approve of that,” Ahmed said.

In early 2011, the RAND Corporation published a paper (PDF) that looked at compound drugs, along with other newly popular medical products, at the behest of California’s Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation. The paper noted that “some parties face significant financial incentives to promote use of these products in questionable situations.” It also noted that the compound drug surge was limited to the workers’ compensation system.

“Other health programs have adopted policies that provide more assurance that drugs are medically appropriate and payments are reasonable,” the paper said. “As a result, they are not experiencing comparable issues related to use of these products.”

Critics say the timing of the compound drug surge was not an accident. In 2007, California’s Division of Workers’ Compensation revised a pharmacy pricing system to discourage physicians from directly dispensing marked-up “repackaged” drugs to workers’ compensation patients. (The New York Times recently covered the issues surrounding repackaged drugs.) People who know the California system suggest that those who were taking advantage of the repackaged drug loophole moved on to compound drugs, among other things, when it was shut. And it was around the time of the repackaged drug clampdown that Ahmed learned about compounding.

Ahmed said a “marketer” introduced him to the concept of compound drugs in 2006 or 2007, and convinced him of their benefits. Ahmed then suggested the idea of prescribing compound drugs to doctors he knew.

“I … talked to some of my doctors, I said, ‘You know, why don’t you try it?'” Ahmed said. “And they tried it on themselves and the doctors loved it. They said, ‘Oh, we’re going to start using this.’ And that’s how I got involved.”

Billing companies like Landmark also benefited from a 2006 decision to repeal a $100 filing fee for workers’ compensation liens — the formal process by which disputed payments are sought in the California system. Gideon Baum, a staff member for the California Senate’s Committee on Labor and Industrial Relations, explained in an interview that “as soon as you got rid of the filing fee, well then you can file a lien on anything.”

“Let’s say someone liens for $70,” Baum said. “You can buy that lien for maybe a dollar or two, and then if you settle it for $10 or $15 or $20, you’re up. And then if you multiply that over thousands of dollars, you suddenly see how it is that these guys are just — I mean, they are printing money.”

Last year, lawmakers in California made a push to remove some of the financial incentives associated with compound drugs in the workers’ compensation system. The bill was known as AB 378.

“Drug compounding — a legal but rarely necessary practice — has exploded as a physician profit-center in Workers’ Comp,” Assemblyman Jose Solorio, then chairman of the Assembly Insurance Committee, said in a statement released in September 2011, a month before the bill he sponsored was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown (D). “That practice must be stopped.”

Landmark fought Solorio’s bill. The company paid tens of thousands of dollars to a lobbying firm to oppose it and dispatched Bruce Curnick, who until recently worked as a Landmark vice president, to the state capital.

One of Landmark’s earliest employees, Curnick is a former attorney who was disbarred in 2000, after the State Bar Court found that he had committed 18 violations of professional rules, including the misappropriation of about $40,000 of client funds, making misrepresentations to clients, disregarding the welfare of seven clients, and acts of moral turpitude. During its coverage of his disbarment, The North County Times newspaper reported that Curnick had received three years probation in 1998 “after pleading guilty to battery and disturbing the peace in a plea agreement stemming from his arrest for allegedly trying to have sex with his 17-year-old baby-sitter in December 1997.” In an interview with TPM, Curnick spoke about his past in general terms, and acknowledged that he had made some “bad decisions,” but said he had put those days behind him. He said he was hired by Ahmed several years ago, after Ahmed offered him enough money that Curnick’s friends started to tell him, “‘Hey Bruce, that’s pretty good money. You ought to go.'”

Curnick claimed credit for organizing the opposition to Solorio’s bill. He spent a year in Sacramento working on the issues related to the legislation, meeting with officials, and being quoted in the industry press that covered the debate.

Like Ahmed, Curnick has spent several decades in fields related to workers’ compensation, and he too believes in the widespread advantages of compound drugs. In a 2010 op-ed written for the website Workers’ Comp Executive, Curnick wrote, “We should congratulate our medical profession on taking the time to place patient care first and become innovative in the practice of medicine,” while acknowledging that “[s]ome legitimate cost controls need to be implemented to prevent opportunists from trying to capture excess profits from this practice.”

According to Curnick, he and his allies helped force a renegotiation of Solorio’s bill when it reached the state Senate.

“We were able to convince the entire Republican bloc in the Senate to not vote on the bill,” Curnick said. “There wasn’t enough Democratic votes to pass the bill. And that forced everybody back to the negotiating table, and then we were able to work something out.”

It is unclear what effect Solorio’s bill has had on the compound drug trends in the workers’ compensation system, or how exactly Landmark’s business was affected. Curnick suggested that doctors had already found a way around the restrictions the law tried to put on the direct dispensing of compound drugs from doctors to patients.

“The bill didn’t really affect the compounders as much as [the insurance industry] thought,” Curnick said. “They couldn’t legislate against administration of the medication. So now all the doctors had to do is administer the compounds in their office, and all of that law didn’t apply anymore.”

Lachlan Taylor, acting executive officer for California’s Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation, said in an interview that it was too soon to tell.

“We will need to come back and look at the situation again to determine whether AB 378 actually accomplished its purposes or if there’s more that needs to be done to finish that job,” Taylor said.

And Rakich, the Assembly Insurance Committee staff member, sounded a more pessimistic note.

“As likely as not, we may have put a crimp on some of the more rampant abuses and sent the clever folks to find a new avenue,” Rakich said. “And that’s constantly our fear, but you know, there’s not much we can do about that until we see something happening.”

Critics of compounding saw, and continue to see, companies like Landmark as unnecessary additional stakeholders in the workers’ compensation system.

“The third-party providers put the whole program together, and make it a little turnkey process for the physician,” Rakich said. “The physician really doesn’t have to go through a tremendous amount of effort, they just have to implement the program, that they probably wouldn’t be able to put together all on their own. Without the third-party arrangers and suppliers, it probably wouldn’t happen on this same level.”

And California lawmakers continue to target other factors that allowed companies like Landmark to boom. The state legislature recently passed a big workers’ compensation reform bill, which, among other things, will affect how liens are filed, and will reinstate a filing fee.

How does someone come to write a six- or seven-figure check to a super PAC? Ahmed’s political awakening occurred at a time when many big Democratic donors still harbored strong reservations about the super PAC era. Democrats, as has been widely noted, were slow to embrace outside spending efforts in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision. Obama actively spoke out against super PACs during the 2010 election cycle. Even after two former White House staff members — Bill Burton, who had been deputy press secretary, and Sean Sweeney, who had been a senior aide to Rahm Emanuel — formed Priorities in April 2011, money was slow to come in. And it was only in February 2012 that the Obama campaign announced it would “do what we can, consistent with the law, to support Priorities USA.” The group made news on its own terms with its anti-Romney ads this summer, and has since even convinced notable super PAC holdout George Soros to give money. But when Ahmed was writing his checks, the summer was still a long way off for Priorities.

No one I talked to for this story suggested there was anything about compound drugs and the workers’ compensation system in California that could be directly affected by federal policy, and with the exception of Curnick, no one even had a theory for why Ahmed had started making major contributions to help Democratic efforts this year. What’s striking about Ahmed’s donations isn’t some connection between his giving and his business — but how quickly someone, anyone, with a big bank account today can go from the vast ranks of small-time givers to the upper echelon of political benefactors.

Curnick, who described Ahmed as a “very ethical business man” and “one of the better self-employed people I’ve ever worked for,” said that Ahmed had never expressed an interest in politics before California lawmakers began pushing measures that affected his business.

“He’d never been involved in politics before until these bills came alive, and then he began to learn how to influence or how to be a part of that,” Curnick said. “And he got over his fear of that, because frankly he didn’t want to get involved in the beginning but he realized he had to. Then… he has a doctor friend of his that took him to a couple of fundraisers for Obama and he got all excited, and he wrote a couple of checks and the next thing you know he feels like the most important man in the world because he’s got all these famous people calling him up.”

When we spoke by phone, Ahmed told me he was introduced to Priorities USA Action “somewhere back a few months ago” by Yolanda “Cookie” Parker, the founder and owner of KMS, a Los Angeles software company. Parker is also an Obama bundler and national finance committee member. (Parker did not respond to several requests for comment.) Ahmed said he was introduced to Parker through a friend, who he would not name. Asked if he had set out with the idea that he would contribute a million dollars, Ahmed declined to say. He did say that he was far from being a billionaire, and that a million dollars represented “a lot of money” for him. And he offered several reasons for why he decided to start giving so generously to Democrats this year.

“I believe in these people because they’re doing good for the community,” Ahmed said. “Obama just gave Americans the ACA Act. That’s my first and foremost, because now people with pre-existing conditions can have health care coverage, and I know how expensive that is. It’s why I love the man. He’s got great policies on immigration. He’s got great policies on religious freedom.”

Ahmed considers himself a philanthropist, and he said he believed Democrats also support “philanthropy.” A Landmark employee sent me a list of donations Ahmed has made, large and small, to several charitable organizations and community groups over the past few years. A short biography of Ahmed prepared by Landmark, sent to me only after my visit to Ontario, noted that he is a member of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Advisory Council, and a member of the Board of Directors of East Los Angeles Community College.

Ahmed is also a member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, an Islamic movement founded in the late 1800s in India by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who the community holds to be the messiah. Ahmed expressed great pride in having helped organize a visit of the Ahmadiyya community’s current spiritual leader, Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, to Congress in late June, when Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA) recognized Ahmed by name during remarks from the House floor.

“You know, I am supporting the Democrats, I support President Clinton, President Obama, you know, Nancy Pelosi, all these other people, because they support philanthropic work, and they give religious freedoms,” Ahmed said. “Look at the respect they gave to His Holiness. … That is my main angle. That is why I’ve been supporting the Democratic community, because I believe they do more than the Republican side.”

Curnick, the former Landmark vice president, returned to his thoughts on Ahmed’s entry into politics at a different point in our interview.

“I think he just kind of got wrapped up in the fervor of the whole thing, and he’s met a lot of very persuasive people and wants to try to fit in, so to speak,” Curnick said. “And [he] has given some pretty hefty sums, which to you and me, it’s a lot of money. To him, it maybe isn’t so much.”

In mid-August, a few days after my first, off-the-record, conversation with Ahmed, and the day after I sent him an email with my questions, as he had requested, I received a phone call from Bill Burton, the co-head of Priorities. Burton told me he had heard I was being “extraordinarily harassing to the people who you’re trying to get to talk to you.”

“Not every person who is interested in investing in the direction of the country is looking to make themselves famous by doing it,” Burton said.

Once IÂ had spoken with Ahmed on the phone, I contacted Burton again, and asked if he could tell me about the start of Priorities’ relationship with Ahmed, and talk about what process Priorities has to evaluate potential donors. Should the medical practices promoted by Ahmed be associated with the Obama reelection effort? Burton declined to answer my questions directly. Instead, a few days later, he sent me a statement by email that didn’t even mention Ahmed.

“Americans who support Priorities USA Action do so because they know that a strong America depends on a President who will fight for the middle class,” the statement said. “While Mitt Romney would certainly cut taxes for wealthy people, supporters of Priorities realize that America’s economy does best when the middle class is doing well.”

I replied with more specific questions, hoping for more direct answers. Burton never responded.

—

Research assistance by TPM’s Casey Michel