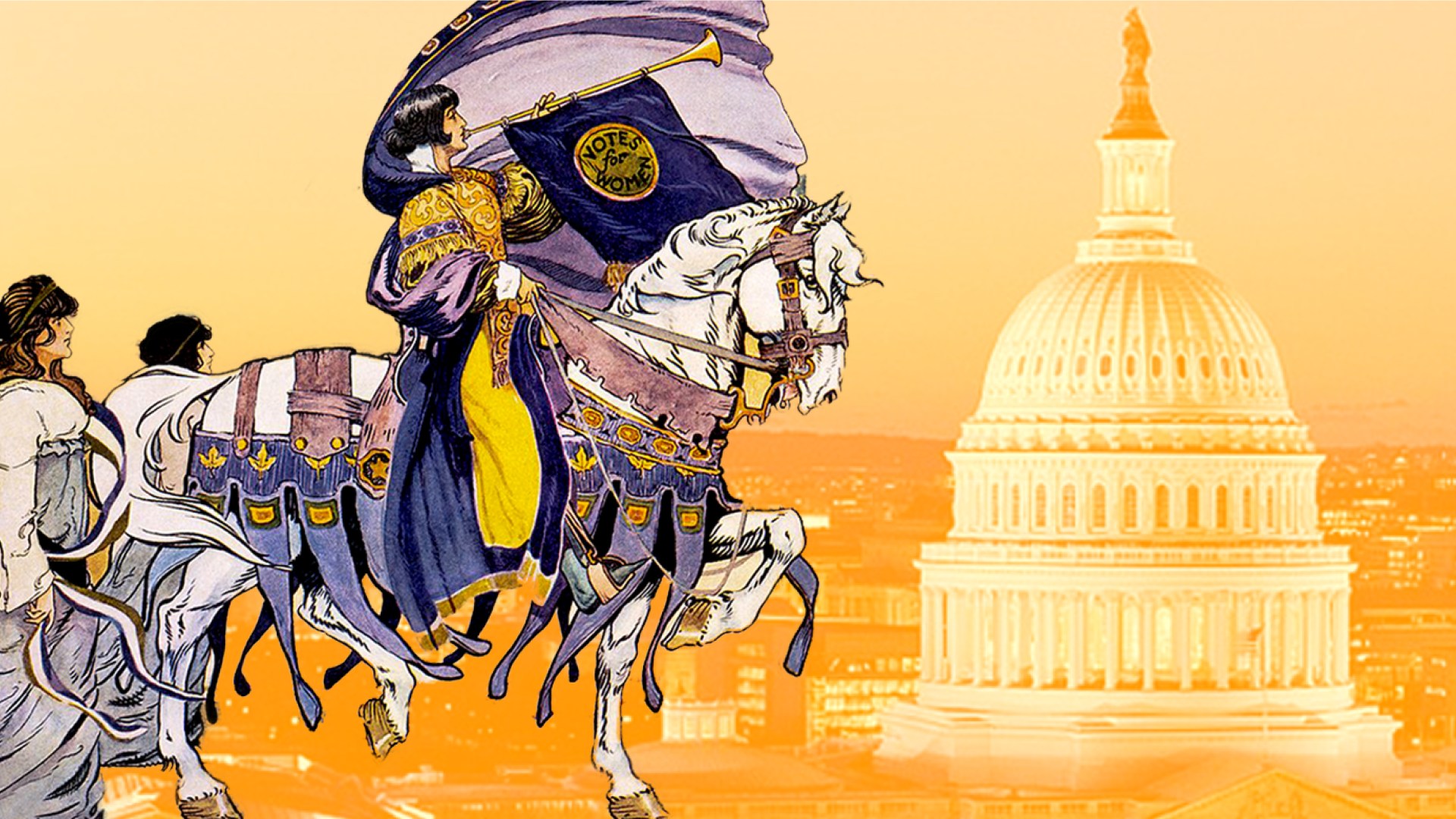

The white horse she straddled stamped impatiently in place as Inez Milholland, cloaked in a white cape that draped over the animal’s broad back, awaited the signal to start the march on the afternoon of March 3, 1913. When the bugle blew, her horse “Grey Dawn” trotted off so quickly from the Capitol Building that the five thousand costumed women marching along Pennsylvania Avenue in the first national suffrage parade lagged several blocks behind. The “beautifulest” suffragist did not know a howling mob awaited her around the corner. Characteristically, she charged into the fray, awing reporters who proclaimed her the suffrage Joan of Arc. No one watching the robust young lawyer would have predicted that just a few years later she would die fighting for votes for women, making her the nation’s sole suffrage martyr.

Nearly forgotten today, Vassar College-educated Milholland—suffragist, lawyer, journalist, socialist, athlete, free lover, pacifist, atheist, labor activist—was the most controversial and celebrated proponent of women’s suffrage during her lifetime.

In the 1910s she was the media’s poster girl for the New Women, the first feminists of the twentieth century, according to historian Nancy Cott. The New Women loathed limits and cherished choice, seeking professional fulfillment and personal pleasure. They were a seminal link between the earnest nineteenth-century woman’s rights activists and the free-spirited women’s liberationists of the late 1960s. It is difficult today to conceive how Milholland dazzled the press and her followers. Princess Diana comes to mind, although Gloria Steinem during the women’s lib years comes closer.

The centennial of Inez Milholland’s death at age thirty in November 1916, right after a woman was almost elected president for the first time, is a fitting occasion to remember that millions of American women labored for seventy years just for the right to vote.

Doing Good and Living Well

Much of Milholland’s character was shaped by her supportive and socially conscious parents. Her father, John Elmer Milholland was a soft-hearted, vocal crusader who had risen from the Adirondack Mountains cabin where he was born to become chief editorial writer in the 1880s for Whitelaw Reid’s New York Tribune. In 1897, Milholland launched a firm that lay miles of pneumatic tube lines beneath Manhattan that he rented to the U. S. Postal Service, betting the federal government would eventually buy the subterranean mail system that was the Email of the Gilded Age.

Stock speculation and the tubes’ financial promise had made him wealthy enough to help launch the very early civil rights movement. Milholland created the virtual one-man Constitution League, which was the forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. When the NAACP was founded, he became its treasurer.

In 1899, Milholland whisked his wife, Jean, and three children to a four-story townhome just off posh Kensington High Street in London. John and Jean continued to shuttle back to New York to attend his business, but they lived much of the time in London until the Great War. At the time of their arrival, Inez was thirteen; her sister Vida, eleven, and her brother John Angus just seven.

In London, Jean hosted the city’s first parlor meeting of Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, which cost her friends even though the militant suffragettes had yet to chain themselves to Parliament. The Milholland home become a way station for political activists passing through London. African American civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell came to tea at the Milholland home, along with Irish revolutionaries and Boer War dissenters.

Inez attended a progressive private girls day school that required students to serve the poor. She later said that volunteering at a soup kitchen where she saw the connection between poverty and female subjugation helped to awaken her feminist conscience. Jean Milholland encouraged her daughters to defy convention, ignoring onlookers’ gasps when the girls galloped their horses along Hyde Park’s Rotten Row astride their steeds instead of sidesaddle. Inez’s London experience exposed her to people and ideas that gave her a broader perspective on the world than most American teenagers.

But besides a social conscience, Inez’s supportive parents also gave her a thirst for luxury and attention. The precocious teenager unabashedly batted her big blue eyes and tossed her chestnut curls to charm hovering male admirers during London’s social season. Milholland’s contradictory inclinations to do good and live well tussled all her life.

In 1905, Inez journeyed back across the Atlantic Ocean to Vassar, where she excelled everywhere except the classroom. Inez played basketball and tennis, captained the field hockey team, and set the school shot-put record. She cut a handsome figure as Romeo in tights in a production of Shakespeare’s play and joined the Current Topics Club, German Club, debating team, and College Settlement. She also volunteered as a city probation officer, sparking her interest in law.

Despite Vassar’s array of empowering extracurricular offerings, the first U.S. college for American women banned any talk of votes for women. The U.S. suffrage movement, in fact, had slumbered since 1896, when Wyoming became the fourth state to grant votes for women.

It began to awaken when Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of woman’s rights pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton, embarked in spring 1908 on an audacious suffrage soapbox tour across upstate New York. Vassar President James Monroe Taylor refused Milholland’s request to invite Blatch to campus.

By then Inez was president of both the junior class and the campus branch of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. One May afternoon more than twenty classmates followed her from the leafy campus to an adjacent cemetery. There they heard arguments for women’s right to vote from Blatch, novelist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, labor organizer Rose Schneiderman, and Helen Hoy, one of a new crop of young feminist lawyers Milholland admired.

Taking New York by Storm

Milholland’s illicit rally launched not only the lively last decade of the suffrage campaign but also her rise as its most glamorous and celebrated messenger. The New York City papers delighted in the defiance of John Milholland’s striking daughter. “Vassar Students Are Now Radicals,” read The New York Times headline. New York newspaper reporters who crowded around the college senior as she stepped off the Lusitania on her return from London that summer. They reported she laughed when asked if marching in the “monster” suffrage rally in which a quarter million people jammed Hyde Park had scared her.

After Milholland graduated in 1909 she moved with her parents into the brownstone they rented that fall two blocks east of Washington Square, immersing herself in Greenwich Village’s heady brew of radical politics and pleasure.

She made headlines that winter when she was arrested and briefly detained while working with the Women’s Trade Union League to protect women picketers from police harassment during the “Uprising of the 20,000” shirtwaist workers strike. The press reported sympathetically on her unsuccessful bid to become Harvard Law School’s first female student. After she graduated from New York University Law School on June 5, 1912, she clerked for prison reformer James W. Osborne. The press marveled when she interviewed Sing Sing inmates in their cells, reporting that she even had herself handcuffed to a prisoner just to see how it felt.

Her name popped up frequently in adulatory newspaper accounts of her suffrage and socialist exploits: chalking sidewalks; soap-boxing in Harlem; portraying Justice in a suffrage pageant; honking the horn as she drove her father’s car full of women in a noisy suffrage caravan; raising $2,000 by passing her hat at a rally featuring the infamous Pankhurst; performing encores of her humorous one-woman suffrage skit at a socialist gathering. She spoke at the Dartmouth Club and Yale University, at smokers and churches, theaters and state fairs, and the New York State Assembly. McClure’s anointed her “The Spokesman for Suffrage in America,” then assigned her to cover the 1912 national suffrage convention.

Newspapers also documented the ubiquitous Milholland’s suffrage activities — by all accounts she was an inspiring orator at a time when women speaking in public remained suspect. She spoke at the Dartmouth Club and Yale University, at smokers and churches, theaters and state fairs, and the New York State Assembly. McClure’s anointed her “The Spokesman for Suffrage in America,” then assigned her to cover the 1912 national suffrage convention.

Milholland made her biggest impact at the head of the large suffrage parades down Fifth Avenue in 1911, 1912, and 1913. The medieval spectacles of banners, floats, and bands won the suffrage campaign more positive publicity than it had received in the past half century, thanks in part to media fascination with Milholland. “No suffrage parade was complete without Inez Milholland,” the New York Sun asserted, “for with her tall figure and free step, her rich brown hair, blue eyes, fair skin and well-cut features, she was an ideal figure of the typical American woman.”

A White Knight

Publicity-savvy Alice Paul, returned from the militant British suffragette movement, recruited this ideal New Woman to serve as herald in the national parade she planned for the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The pair clashed almost as soon as Milholland arrived in Washington and learned that Paul had denied black Howard University students’ request to march. Paul reversed the decision when Milholland threatened to quit.

Lawyer Inez Boissevain, wearing white cape, seated on white horse at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C. via Wikimedia Commons

Milholland played the part of the suffrage movement’s white knight when a drunken mob swarmed the women marchers minutes after they left the Capitol. Police, annoyed by the parade plans, did nothing as men grabbed women on the floats and cursed and spat at marchers. Milholland was an accomplished equestrian and, in the saddle, taller and faster than the men around her. She spurred “Grey Dawn” into the crowd. “You men ought to be ashamed of yourselves,” she shouted.

They fell back, and she kept moving. Within minutes, cavalry troops Paul had called in from nearby Fort Myer galloped up Pennsylvania Avenue to clear a path for the suffragists, who struggled for hours to reach the Treasury Building, where an audience awaited their arrival to start Hazel MacKaye’s epic feminist pageant, The Allegory. An anxious MacKaye finally heard bands and saw banners. “Now there appeared a gallant figure out of the pressing throngs,” she recalled, “a girl in white upon a white horse, dressed in flowing Crusader’s cloak—Inez Milholland ‘the most beautiful suffragette’—and the most courageous.”

Newspapers from the Atlanta Constitution to the Los Angeles Times described her heroism; the Chicago Tribune was among those that placed her photograph on its front page. Five days of Senate hearings condemning the mayhem boosted suffragists’ cause. Testimony and editorials asserted women’s right to public space, a key step toward recognizing their civil rights. Wilson met with Paul on March 17, and the Senate reactivated its Woman Suffrage Committee, which that June issued a favorable report for the first time in more than twenty years.

A crack opened in the door to a federal constitutional amendment that would grant all American women the vote in one fell swoop, bypassing the laboriously redundant state-by-state approach of the main suffrage organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Much credit belonged to Milholland, who by taking the reins into her own hands forced the public and politicians to take suffragists seriously.

Free Love

Life for a New Woman was not all work and no play. Milholland happily exercised her sexual power over men; she once referred to herself as a “hunting leopard.” An early admirer was twenty-nine-year-old inventor Guglielmo Marconi, who captivated the Milholland brood with his new wireless machine when they crossed the Atlantic aboard the Lucania in 1903. Seventeen-year-old Inez accepted his marriage proposal but the engagement seemed fanciful. He married a teenaged Irish baroness the next year but remained lifelong friends with Inez.

Milholland also practiced the free love that Villagers preached a half century before the sexual revolution. Besides dalliances with college men and British nobles, Milholland enjoyed romances with handsome socialist Max Eastman, when both were rising radical stars in the Village; the unhappily married Upton Sinclair; and fifty-year-old John Fox Jr., also married and the author of the blockbuster, Trail of the Lonesome Pine. Milholland kept suitors well-apprised of their rivals; unlike many other New Women, she had no trouble keeping her own needs first in these relationships. Fox complained that she was self-centered when she broke up with him soon after she had wangled him into donating a thousand dollars to ex-boyfriend Eastman’s new socialist magazine, The Masses.

Milholland shocked the nation when word leaked in the summer 1913 that she eloped in London with the scion of a Dutch newspaper publishing family and cousin of her erstwhile fiancé, Marconi. Dashing Eugen Boissevain, thirty-three, was an adventurer with a laugh and lust that matched hers. He wooed her when both shared a suite of rooms with Marconi and his wife on a ship sailing to London. Inez proposed to him three times before they docked. When they arrived at the Marconi family’s fabulous coastal estate, Eaglehurst, they made wild love in its tower.

They married quietly soon after on July 14 but declined to exchange rings, which she dismissed as a “badge of slavery,” although Inez did tack his last name onto hers. She had just begun writing a short-lived column for women in McClure’s that illuminated her frank views on women’s right to sexual fulfillment. Several readers canceled their subscriptions when she wrote that wives unfulfilled in marriage should seek sexual satisfaction elsewhere. In letters they exchanged during their frequent separations, she joked with Boissevain about “Simon,” their nickname for his penis, and she described how she came to orgasm fantasizing about him.

Career and business often separated the couple as they attempted to put into practice the egalitarian marriage reimagined by New Women like Milholland. Of course she would continue working both as a lawyer and for suffrage, she assured reporters. Privately, she acknowledged professional frustrations. She had to stay behind when her firm’s male lawyers traveled to Buffalo for a big libel trial to avoid any sexual innuendo. Law association bans against women blocked crucial networking, so New York women lawyers formed their own association whose monthly journal Milholland edited. She lost her American citizenship when she married due to a federal law that assigned wives their husbands’ nationality. No one tried to stop her from practicing law, which Milholland feared, but the overnight loss of citizenship made her even more sensitive to the importance of votes for women.

Boissevain, however, proved a model “New Husband” throughout her professional setbacks. He was unthreatened by her celebrity. “I like to look up to and admire the people I love,” he shrugged. But the marriage suffered strains. He started a Dutch Indies tobacco import business that floundered, and her father grudgingly helped pay the rent of their two-bedroom flat in midtown Manhattan. Milholland also yearned for a child. One night the couple cried together about their inability to conceive.

Despite these domestic worries, Milholland continued her crusades for social justice. She tried to organize female retail clerks at the palatial department stores that had expanded women’s job opportunities but were paying them poverty wages. She presided at a “Free Press Protest Meeting” at Cooper Union that defended ex-lover Eastman’s Masses against a criminal libel charge brought by the Associated Press. She joined pacifist protests to keep America out of the disastrous war that had broken out in Europe in August 1914.

The day book. (Chicago, Ill.), 03 Jan. 1916. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

An opportunity to help speed the peace materialized when Italy appointed Marconi to oversee its military wireless operations. Inez quit her job and sailed with him to report on the war in Italy. She hoped bearing witness could help convince Americans to stay out of the war, but she was also drawn by the romance of foreign correspondence and by Eastman’s estimate she could earn thousands if she landed a few lucrative interviews. And her ego needed a boost. Unbeknownst to her adoring public, their “Amazon” considered herself a failure. “I have no value,” she wrote Eugen as one of her periodic bouts of depression descended.

Milholland sailed on May 22, 1915, two weeks after twelve hundred Lusitania passengers died when a German U-boat torpedoed it. Male journalists in the Dolomite Mountains acted solicitous of Inez but secretly protested her presence. “You cannot imagine the fun and excitement of being the only woman,” she teased Boissevain. When the government recalled her to Rome, she consoled herself by sleeping with an Italian officer. She revealed all to her husband, whose façade of modern indifference to her infidelity quickly crumbled. Eugen was also disappointed that she was not taking her work seriously. Before racing to her side in Naples, he wrote: “Please don’t be a dilettante at it.”

But Milholland bounced from cause to cause, from a campaign to stop the execution of a farmhand convicted of murder to programs to train rather than punish prostitutes, whom New Women believed epitomized the perils of women’s economic dependence on men. After the Italian debacle, she also threw herself back into the struggle for the women’s vote. Then Milholland left her husband again in December to join Henry Ford’s quixotic Peace Expedition. Desperate to make her mark in the world, she joined some one hundred-fifty notable Americans who at the automobile magnate’s expense sailed to a Ford-financed peace conference in Stockholm to present a European mediation plan he tasked them to devise during their voyage. Metaphorical stormy seas rocked the squabbling would-be peacemakers. Ford literally jumped ship in the middle of the night in present-day Oslo and a dispirited, freezing Milholland quite a few days later. She returned to Eugen feeling “punk.” He beseeched her never to leave him again.

Women First

As the 1916 presidential election neared, Alice Paul pressed forward with a bold plan to create a Woman’s Party to campaign for a federal suffrage amendment. Paul’s strategy was revolutionary because it asked the four million women in the eleven western states where women now voted to align themselves politically with their gender instead of with the male-led political parties. The nonplussed New York Times editorialized against Paul’s “political blackmail.” Milholland supported Paul’s slogan of “Women First!,” a reference to the new party’s refusal to let suffrage take second place to war. “Suffrage for women is a gift of no one to confer,” Milholland declared in her speech at the Woman’s Party founding convention in Chicago in June 1916. “It is a right!” As she tossed her trademark picture hat on the dais, Inez joked she was throwing her hat in the ring. The crowd responded generously when she called out for cash for the cause. Suffragist Mabel Vernon a half century later remembered Milholland’s charisma that afternoon: “Not just beautiful, but brilliant.”

Exhausted from work, worry, and a vague malaise, Milholland tried to beg off when Paul asked her to become the party’s “special flying envoy” in the West to campaign against Wilson, who had refused to come out for votes for women. Inez was also uneasy about aiding “stuffed shirt” Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes. Paul enticed her with an invitation to deliver the campaign’s keynote in Chicago. John Milholland, who harbored political ambitions for his daughter, urged Inez to go and glow in the national media spotlight. He donated five thousand dollars to the Woman’s Party and arranged for Vida to accompany her sister. Boissevain said he supported whatever his wife chose to do. Inez reluctantly agreed but warned Paul she was a queasy traveler.

The sisters left New York on October 4 on the eighteen-hour train trip to Chicago. Inez, however, felt so ill she canceled a scheduled street meeting and went straight to bed at the luxurious Blackstone Hotel. She visited a doctor, who diagnosed a chronic tonsil infection but proclaimed her otherwise a “perfect specimen of physical womanhood.” He prescribed arsenic and strychnine. The sisters endured the overnight ride on a private railroad car to the first official stop in Cheyenne, Wyoming, but Inez stayed in bed all day before her joint appearance that night with Blatch. Inez rallied and wowed the Plains Hotel audience.

This pattern of spending days in bed and dazzling crowds at night before boarding trains after midnight continued through stops in Pocatello and Boise and across Oregon. Crowds adored the exotic Eastern envoy with the cultured British accent, although she did not reciprocate. “I think the American people so unadventurous and stale,” she wrote Eugen on the train from Wyoming. “I am frank to say that unless I was as busy as I am every minute I could not stand such a trip without a love adventure.” In Seattle, she visited another doctor who was so shocked by her scarlet, swollen throat that he wanted to operate immediately.

Milholland refused to quit. She needed a success to inflate her punctured self-image following the failures in Italy and on the Ford expedition. Inez also believed her appeal to sisterhood was sacred. “It is women for women now,” she entreated listeners, “and shall be till the fight is won.” That evening she enraptured her audience. A reporter wrote she was “more like a blazing spirit of freedom, than a beautiful girl with a boyish stride.” An all-night train ride to Spokane followed, then more stops across Montana. She considered quitting when she woke up in Butte unable to stand. She summoned another doctor who diagnosed severe anemia. He prescribed more strychnine and strong coffee.

“Lo and behold, I got out of bed—and worked,” she wrote Eugen. Next the sisters sped through Utah and Nevada. They arrived in Sacramento nearly totally depleted on October 21 at 5:55 a.m. After an automobile rally and women’s luncheon they boarded the crowded day coach to San Francisco, where Inez hid her illness from a steady stream of reporters at the Palace Hotel before addressing some fifteen hundred people in its ballroom. She could not sleep that night, and felt wretched the next day. Late that night Vida and a porter worked feverishly to revive Inez as she lay limp and panting in the city’s train station awaiting another train to Los Angeles. They finally arrived just a few hours before Inez’s widely publicized speech was to begin at Blanchard Hall. The sisters summoned another doctor, whom Inez instructed to “fix her up.”

Whatever he gave her worked; she seemed on fire to the standing-room-only crowd. But her head was swimming. She asked, “President Wilson, how long must this go on?” She raised her arm to make a point, then collapsed. The audience gasped as supporters carried her off to a dressing room. Revived, Inez insisted on finishing her speech, although she sat in a chair. Back at her room at the Alexandria Hotel, another doctor finally told her to stop the tour or die. The infection had affected her heart, and she needed to have her tonsils and several infected teeth removed as soon as possible. Inez refused but keeled over when she tried to stand. After she entered Good Samaritan Hospital on October 24, a blood test revealed she suffered from pernicious anemia, a serious disease in the years before researchers discovered vitamin B12 shots or pills cured it.

Doctors removed her infected teeth and instructed her to convalesce for three weeks before the throat surgery. Eugen arrived at her bedside as newspapers kept the shocked nation posted on her roller-coastering condition over the next month. Then pleurisy inflamed her lungs. On election night, Vida called her parents in Manhattan to tell them Inez was dying. She died surrounded by family on November 25 at 10:55 p.m. Her devoutly Presbyterian father and irreligious husband literally fought over Inez’s body, which Eugen insisted his atheist wife wanted cremated without fanfare. John won, and the Milhollands buried her in a quiet religious ceremony on a hill at the family’s Adirondacks estate, Meadowmount, a gentleman’s farm on the site of John’s childhood home. Tributes and editorials reflected the broad swath of her influence. Some called her a martyr.

Photograph of Alice Paul and a group of young women in white costumes with headbands, standing at Inez Milholland’s gravesite. via Wikimedia Commons

Paul could not agree more. Milholland’s death ushered in the suffrage movement’s final, most militant phase. On Christmas Day, Paul arranged the first memorial service for a woman ever held in the U.S. Capitol Building. The solemn pageantry ended on a combative note, calling on Wilson to give Inez’s death meaning by coming out for the federal suffrage amendment. He agreed to meet the Inez Milholland Memorial Deputation of some three hundred women in the East Room on January 9, 1917, but angrily stalked out after a stream of speakers lectured him on his responsibility to stop more women from dying for the right to vote. The next day Paul’s militant suffragists initiated two years of public protests with an unprecedented picketing of the White House. A silk banner proclaimed Milholland’s final public words, slightly revised to read “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”

These protests evoking her image elevated Milholland from suffrage celebrity to feminist icon. A few of the nearly 100 jailed over the following months went on a hunger strike; guards force-fed Paul, a barbarism that backfired. The bad publicity Paul’s pesky militants stirred against Wilson in conjunction with the tamer strategy of the larger, more conventional suffrage organization—knitting socks and such for U.S. soldiers in Europe to prove women worthy of the vote—finally had an effect.

On the eve of the next session of Congress, Wilson came out for woman suffrage: the House voted for the suffrage amendment on January 10, 1918, exactly a year after picketing began. More protests followed, including the August 6, 1918, celebration of Inez’s birthday, when a hundred suffragists climbed Lafayette Monument, before Wilson signed the Nineteenth Amendment establishing women’s right to vote on August 26, 1920.

Ninety-six years later, more than 100,000 women have already signed up for the Women’s March on Washington on January 21, the day after Inauguration Day 2017. Most won’t know it, but the woman on the white horse led them there. The poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, whom Eugen Boissevain wed in 1923, wrote in a sonnet dedicated “To Inez Milholland,”

“Only my standard on a taken hill

Can cheat the mildew and the red-brown rust

And make immortal my adventurous will.

Even now the silk is tugging at the staff:

Take up the song; forget the epitaph.”

The Inez Milholland Tour

Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument

144 Constitution Avenue, NE

Washington, DC 20002-5608

(202) 546-1210

This 200-year-old Georgian house on Capitol Hill was headquarters of the National Woman’s Party, which bought it in 1929. Tours and special programs at the house, which features an oil painting of Milholland as the 1913 parade herald and hundreds of artifacts from NWP campaigns for votes for women and the Equal Rights Movement, which Paul wrote in 1921. Florence Bayard Hilles Feminist Library is open for research in the party’s extensive archives.

Meadowmount School of Music

1424 County Route 10

Westport, N.Y.

(518) 962-2400

Each summer, the jumble of mountainside buildings that comprised the former Milholland family estate houses one of the world’s foremost music schools. The public can enjoy concerts by its talented young violinists, cellists, violists, and pianists —Joshua Bell and Itzhak Perlman are among its alumni—and special guests during the 2017 concert season June 30 to August 9.

Meadowmount presents concerts Wednesday, Friday and Sunday at 7:30 p m. in the 500-seat Ed Lee and Jean Campe Memorial Concert Hall. Concerts begin Admission for regular concerts is $10 for Adults, $5 for Students and Senior Citizens.

Inez Milholland Grave

Lewis (Center) Cemetery

933 Fox Run Road

Elizabethtown, N.Y.

Not far from Meadowmount, a six-foot slab marks Inez’s grave in the family plot in a copse of pine trees at the top of the hill adjacent to the First Congregational Church in the hamlet of Lewis. The church is on the National Register of Historic Places. John Milholland’s parents are buried in a front section of the cemetery. From the hill you can see Mt. Discovery, which her father called Mt. Inez. The link above is a guide can help you find the graves.

Iron Jawed Angels (HBO, 2004)

Julia Ormond plays Inez in a few brief scenes in this star-packed film about of Alice Paul. Critics may cringe at the Hollywood makeover of Paul, played by Hillary Swank, but German director Katja Von Garnier and a rock-music score capture the suffrage pickets’ courage.

Linda J. Lumsden is an associate professor in the School of Journalism and affiliated with the Department of Gender & Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. The paperback edition of her 2004 book, INEZ: The Life and Times of Inez Milholland (Indiana University Press), was published in September. She is working on a book entitled, Journalism for Social Justice: A Cultural History of Social Movement Media from Abolition to #yesallwomen.