“What a crazy week,” said Eric Gundersen, CEO of MapBox, a cloud-based digital map publishing company, in an interview with TPM.

Gundersen’s point is well taken, given his small 25-person startup, based in Washington, D.C., just won a $575,000 grant from the journalism innovation nonprofit the Knight Foundation.

The grant was awarded to MapBox specifically to allow the company to focus most of its resources over the next few months on improving its own main source of map data, OpenStreetMap, a free crowdsourced world map created by volunteer cartographers. It’s helpful to think of OpenStreetMap (OSM) as the “Wikipedia” of digital maps (although it’s not actually tied to Wikipedia). MapBox is an outside private company that uses the OSM data to build maps and mapping software, much of which it makes open source, for anyone to use for free, but some of which is proprietary and which it charges high prices to other companies and government agencies to access.

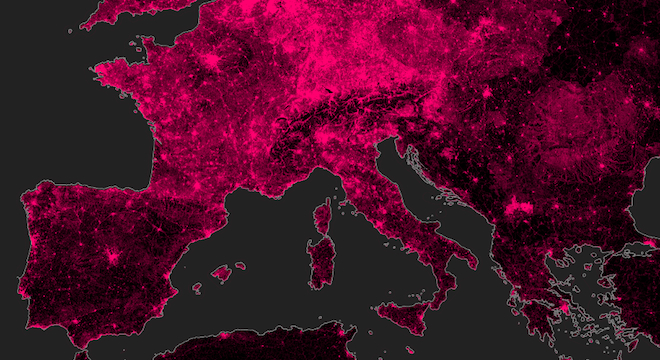

Here’s an example of MapBox maps of an employee’s running routes, made using OSM data:

But when he said the week was crazy, Gundersen wasn’t just referring to the half-million-dollar award that will allow most of his team to take what he calls “almost a paid sabbatical” to work on improving OpenStreetMap.

Instead, he was also directly responding to two other massive developments in the digital mapping industry.

The first: Apple’s recent bungled attempt, when releasing its new mobile software update iOS 6, to replace Google Maps on the iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch with a considerably inferior, glitchier map system of its own making, a map system that uses some data from OpenStreetMap and Dutch GPS company TomTom.

The second: Amazon’s announcement on Monday that it would be launching a maps platform of its own, using data obtained from Nokia, which in turn acquired it along with a company called Navteq, which then started, as many digital map makers do, with data from the U.S. Census, known as TIGER.

All in all, as a result of these developments, Web and smartphone users’ interests have recently been piqued in the digital mapping space — a space which until this week remained primarily the providence of professional companies, trained cartographers and highly devoted amateur map-makers, the lot of whom were mostly obscure to those outside their communities.

“Weeks like this are gamechangers for the space,” Gundersen told TPM. “For many people, like ‘Holy shit, there’s more than one map in the world. Maps are different from one another. Maps matter on a really fundamental level.'”

The “one map” Gundersen thinks most people are familiar with is, of course, Google Maps, the most popular digital map website in the world according to third party tracking firm Alexa.

But Gundersen and the rest of his company, along with the nearly 800,000 volunteer cartographers from around the globe who contribute to OpenStreetMap, believe that Google Maps won’t always be the most popular, especially if they have anything to do about it.

“I have a tremendous amount of respect for Google,” Gundersen told TPM. “I like how they went ‘whole stack.’ It’s a real honor to get to compete with them.”

Going “whole stack,” in Gundersen’s world means that Google, as it developed Google Maps over the past seven years, did so by moving from the seeds of small acquisitions of other map companies to the behemoth that it is today, acquiring many technologies and personnel along the way, and creating many innovative features of its own, such as its StreetView surveying teams.

But the tide is clearly shifting away from Google Maps, at least as a go-to source of mapping data by other large tech and Web companies. In the past year alone, Apple, Wikipedia itself and Foursquare have all ditched Google Maps data in their websites and services for OpenStreetMap, in some cases the OpenStreetMap-based products provided by MapBox. When Craigslist began experimenting with maps in its local real estate listings in August, it too turned to OSM instead of Google.

The reasons for many of the defections may have been primarily business related, as Google in 2012 began charging for heavy use of its Google Maps application programming interface (API), charges that it recently slashed, but didn’t eliminate entirely, after hearing “feedback” from customers.

But following the Apple Maps disaster — its new map software has been panned around the globe for providing bad location data and directions — many individual users are questioning the worth of leaving Google Maps behind.

Here’s a screenshot of one warped Apple Maps 3D view, posted online by LinkedIn software engineer Jeremy Johnstone:

However, Gundersen sees the moment as an opportunity to help bolster OpenStreetMap and prove its worth — not only to individuals, but to other businesses as well.

“In a few years, I don’t think Apple’s going to be going to Tom Tom or that Amazon’s going to be going to Nokia and Navteq for their map data,” Gundersen told TPM. “There are certain things where there becomes a need for a common good, and mapping is one of them.”

There’s no question that now and increasingly so in the coming years, digital mapping accuracy and utility will be a major global issue, as maps and geolocation services are among the most commonly used features on smartphones, which are becoming the world’s go-to computing device (not to mention the fact that many apps rely on geolocation data from the built-in apps available on a given phone or tablet).

To help improve OpenStreetMap, MapBox will begin by improving its tracing interfaces — that is, the ability for users to trace and fix traces of publicly available satellite imagery of locations, which OSM’s wiki notes may often “have offsets to the real positions of objects on the ground.”

MapBox has already developed and published open source tools in order to improve OSM tracing (some of which use Microsoft’s Bing Maps), but now they’re going to really push even further to make it as easy as possible for newbie volunteer cartographers.

MapBox will also work to improve OSM’s community webpages, to encourage more volunteers around the globe to help the effort, and improve the OpenStreetMap application programming interface to make it easier for developers and others to tap into OSM data, add to it, or draw upon it for their own apps.

“OSM is not about the map itself, it’s about the data,” Gundersen said. “That’s where this investment is going — toward improving the collection. We’re focusing on three specific areas: making it easier to add data, building up the community, and making it easier to get data out.”

As for whether MapBox’s own increasingly lucrative, paid mapping products and services (it charges between $0 and $499 a month for hosting maps for outside apps, with the price increasing proportional to increasing number of views those maps get) will ever present a conflict of interest in its goal to improve a free source of map data in the form of OpenStreetMap, Gundersen said he doesn’t foresee any problems.

“I see OSM becoming one of the greatest open data sets for all of us around the world,” Gundersen said. “We see our success critically tried to OSM and we cant think of an example where there that wouldn’t be true.”

And as for the question of why the Knight Foundation didn’t simply award its grant to the OpenStreetMap Foundation, the nonprofit that oversees the global mapping project (similar to the Wikimedia Foundation that oversees Wikipedia), Gundersen said “we’ve got the team. We’re ready to go now.”

Gundersen anticipated spending all of the money from the grant on OSM improvements by the Spring of 2013.

MapBox was founded in 2010 as an offshoot of another digital mapping and data visualization company called DevelopmentSeed.