Was Abraham Lincoln, the ‘Great Emancipator’, a racist? This question is raised again by the news that a copy of a book about ‘racial science’ has been identified as having Lincoln’s handwriting in its pages.

It’s a perennial question, a deeply anachronistic question, but also a critically important one given Lincoln’s role as perhaps the most revered and significant political figure in all of American history. It’s also a question I have some level of expertise on. So without trying to answer the question in a definitive way, I thought I would provide a few factual guideposts about how to approach the issue and what we know.

The first is that there is little doubt that by judged by early 21st century standards, at least until well into his presidency, Lincoln was “racist”.

Second, you cannot take Lincoln’s public utterances on the issue of race, certainly not through 1860, at face value. Virtually everything Lincoln said on the topic was aimed at combating Democrats who wanted to paint him as being a supporter of “social equality” – the key catch word at the time – between the races. This doesn’t mean we should substitute more racially palatable views in place of things he actually said. But his public statements simply cannot be taken at face value as a reliable gauge of his beliefs.

As a side note, it’s important to remember that in the 1850s, anti-slavery sentiment was not at all inconsistent with racist sentiments, often virulent racist sentiments. As hard as it is to make sense of from our 21st century perspective, many anti-slavery Northerners saw black slaves and slaveholders as almost in league as a common threat to free whites. And that often applied to free blacks as well.

But back to Lincoln.

In the late 1850s Lincoln was a consistent though moderate anti-slavery politician. He was never an Abolitionist. It’s also clear, though, from various statements, public and private, that the injustice of slavery was central to Lincoln’s opposition to it – a fact that set him apart from many anti-slavery politicians of the era and I suspect played a critical role in his evolving views during his presidency.

By late in his presidency, Lincoln’s views about blacks, their future role in American society and the role of slavery in the unfolding of American history had changed dramatically. Whether he believed that blacks were truly equal to whites in all respects as opposed to simply entitled to equal rights seems questionable to me and probably impossible to determine, given the limited evidence available and the abrupt end of his life.

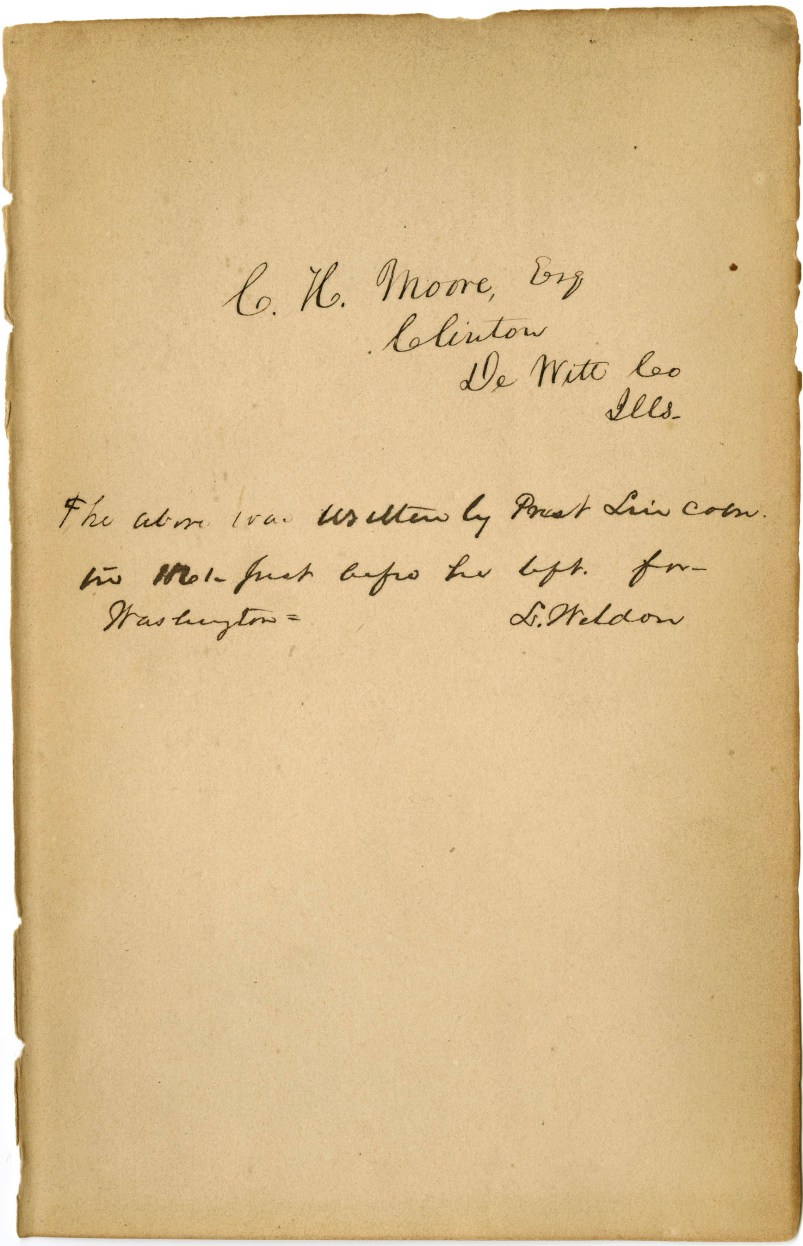

The book that has raised these questions again is Nott and Gliddon’s Types of Mankind. The essential claim of the book is that that different ‘races’ of humans lack a common ancestry. Whites and Blacks amount almost to separate species that originated separately, though obviously they had no difficulty reproducing – something 19th century Americans were of course well aware of.

The backstory of this work is important to understand. As belief in equality and opposition to slavery grew in the United States and Western Europe in the early 19th century, there was what turned out to be a rearguard effort to enlist science to defend the institution.

In the 18th century and early 19th century, most white Americans – especially but not only in the South – saw little need to justify slavery. Indeed, at least at the elite level there was a general consensus that slavery was an unfortunate reality and one that should in theory probably not exist but did exist. Something society should grow out of … but not yet.

But as opposition to slavery became more widespread and the threat to the institution more concrete, defenders of slavery began looking around for positive defenses of the institution. Not just ‘yes it’s unfortunate but that’s the way it is’ but it’s a positive good and this is just as it should be.

We see signs of this in the mid-late 1830s with arguments that white men could only be truly free and equal if there was enslaved black underclass to undergird that freedom. See Calhoun’s “Positive Good” speech from 1837. But over the course of the 1840s there was an increasing effort to buttress slavery with ‘science’.

This is the backdrop of pro-slavery ideology in the late 1840s through the Civil War. And Types of Mankind (see the text here) is part of that conversation – an attempt to enlist science in the effort to show that slavery was proper, good and inevitable. Notably, the authors rejected both the bible and evolution.

Given that backstory and the fact that this book was seen as part of the movement of pro-slavery racist pseudo-science – even denying a common humanity to Africans, it seems unlikely that Lincoln would have embraced its contents.