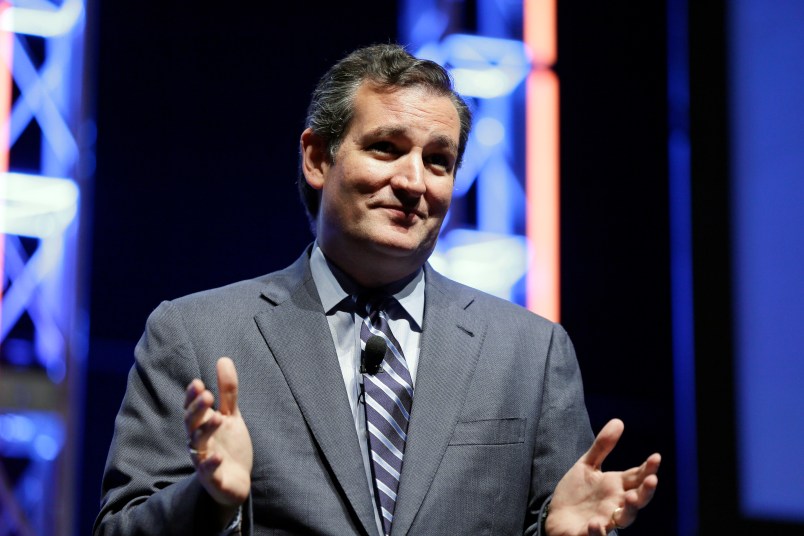

Here’s another piece of the puzzle on Ted Cruz’s eligibility. Bryan A. Garner has written a “legal memorandum” at the Atlantic on the various legal questions that come into play in determining with Cruz is a natural born citizen. As with other serious looks at the issue in recent days, I’m struck by how complicated, unsettled, and genuinely up in the air the legal question actually is.

Garner ultimately concludes that a court would find Cruz to be eligible, but it’s not an easy or straightforward call, and it’s predicated on several untested assumptions precisely because there are not prior court rulings that you can point to and say, ah ha!, this is the definitive answer. But one part of his analysis in particular jumped out as a key element.

I’m going to simplify things a little for the sake of clarity, but the basic notion in early English law was that to be considered a natural born English subject you had to be born on English soil. Period. End of sentence. (We have some more background on this from Mary Brigid McManamon, who wrote an op-ed this week on the subject in the Washington Post.) But over time, by statute, Parliament liberalized that restriction, in particular statutes passed in 1708 and 1731. Ultimately they provided that children of natural born fathers who were born extraterritorially were treated as if they themselves were natural born subjects.

So a big question in Garner’s analysis is whether America’s adoption of English common law encompasses the older understanding that natural born status was limited to those born territorially or the newer notion embodied in statute that treated those born outside England to natural born English fathers as natural born, too. Garner says, yes, America’s adoption of English law would have include those later statutes, and the Supreme Court has broadly said this already:

A further question arises: to what extent was a 1708 or 1731 statute incorporated into American law? The answer is that they are entirely applicable. According to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1831: “These statutes being passed before the emigration of our ancestors, being applicable to our situation, and in amendment of the law, constitute a part of our common law.” In his 1828 Commentaries on American Law, James Kent had used virtually the same words.

Garner’s point is that the 18th century English statutes directly inform the framers’ understanding of the term natural born as they used it in the Constitution and, perhaps more to the point, were enshrined in American law from the very beginning.

There’s quite a bit more to Garner’s analysis and almost unbelievably the fact that Cruz was born abroad to a natural born mother is a serious complication in the legal analysis since the British statues only eased the restrictions for those born to natural born fathers. Garner eventually concludes that the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clauses means no modern court would rule Cruz was ineligible simply because his mother rather than his father was the natural born citizen.

We’ll leave for another time the irony of an uber-conservative strict constructionist being rescued by application of the equal protection clause to a gender disparity.