As we witness this unexpected and I think historic sea change at least in the symbolism of neo-Confederate nostalgia, it is worth remembering that the fight for equality and civil rights for African-Americans and against white supremacy in its various forms has never been a march in a single direction. If the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, it’s very much been a zigzag arc.

Even after the federal government withdrew its final support from Reconstructed, biracial governments in the South in 1876, those governments and movements didn’t collapse overnight. Biracial politics and political movements continued on in diminished but persistent forms well until the 1890s, before being finally snuffed out in a wave of Supreme Court decisions, mass disenfranchisement and violence. As Gregory Downs noted in his article on the origins of Juneteenth, in the 1890s there were some 100,000 African-American voters in Texas. By 1906 that number had fallen to fewer than 5,000. The blanket of Jim Crow absolutism that had come to rest over the South by the first years of the 20th century may have looked like some time immemorial reality. But it was actually a very new creation, finally secured only in the 1890s through an interlocking chain of Supreme Court decisions, extra-judicial violence, new legislation and the collapse of interracial political coalitions.

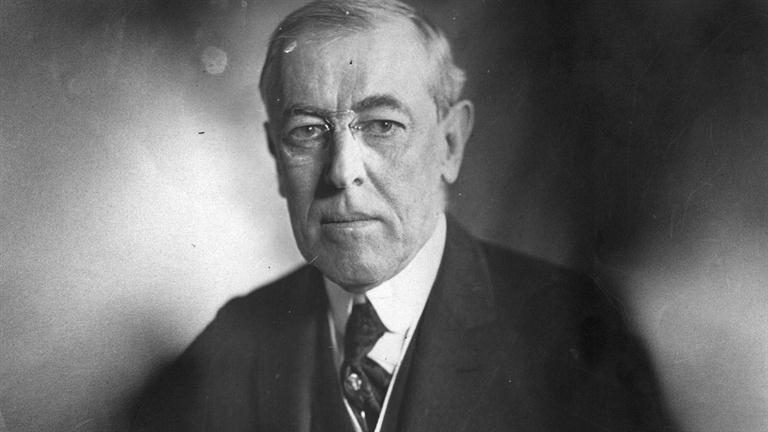

One of the legacies of the Civil War was a near unbroken Republican dominance of the presidency for a half century after the end of the Civil War – with the anomalous exceptions of two non-consecutive terms of Northerner Grover Cleveland, elected in 1884 and 1892. That dominance came to an end in 1912 when a division between establishment (Taft) and reform (Roosevelt) Republicans allowed the election of Woodrow Wilson, the governor of New Jersey who was nevertheless very much a Southerner, born and raised in Virginia.

Even after the North and the national Republican party withdrew military support for black political rights in the South it still remained supportive of black civil rights in a more limited but still significant way. Because of that, black voting support for the GOP then was as strong as it is for the Democratic party today, where black voting was still permitted. One of the key places that support evidenced itself was in federal hiring.

That brings us back to President Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States.

The 1912 presidential election featured not only a historic fissure in the Republican party, it also featured two candidates associated with the Progressive Movement, Wilson and renegade Republican and former President Theodore Roosevelt running on the Progressive Party ticket. Wilson is known and still honored as a Progressive reformer on the domestic front and his foreign policy is still referenced as the embodiment of idealistic foreign policy engagement, putting democracy rather than realpolitik at the center of policy formulation. Yet to say that Wilson was a disappointment on civil rights is a colossal understatement.

Future President Woodrow Wilson and Ellen Wilson, 1910

It’s not hard to find anecdotes about Wilson’s celebration of the racist tour de force Birth of a Nation, the country’s first cinematic blockbuster. But Wilson’s racism went far, far deeper. We rightly judge people at least in part in the context of their times, not ours. But even judged against the standards of his own day, Wilson was a racist and a throwback, committed to turning back the limited gains African-Americans had held onto after Reconstruction. As an historian and political scientist, Wilson played a part in the historiographical reimagining of the Reconstruction years as a period when half savage blacks ruled over white Southerners in connivance with corrupt Northern extremists before being overthrown by white southern “redeemers” in the last two decades of the 19th century. Nor did Wilson leave his racism in the realm of ideas.

When Wilson came to Washington he quickly instituted a purge of African-American federal workers in Washington and around the country. Where purges weren’t possible, federal workplaces were re-segregated, often with surreal and hideous results. Even more than Wilson, Wilson’s wife Ellen, a Georgia native, was a visceral racist who was shocked to see the limited level of integration then in place in the nation’s capital. She was reportedly especially disgusted to see black men and white women working in the same workplaces and took a personal role in pushing forward resegregation in Washington, DC.

Numerous African-American federal workers were fired, in many cases by white Southern Democratic appointees. The Post Master General and the Treasury Secretary both re-segregated their departments and gave supervisors free rein to fire African American employees at will. In Atlanta, 35 African-American postal workers were summarily fired. Similarly stories took place throughout the country. Wilson’s Collector of Internal Revenue in Georgia said in 1913, “There are no Government positions for Negroes in the South. A Negroes place is in the cornfield.”

Significantly, not only did Wilson’s Southern backers see his election as an opportunity to remove the little remaining federal intrusions on race relations in the South. They also saw it as an opportunity to expand them into the North, where many believed, with some reason, they would find a welcome reception among Northern whites. Federal workplaces introduced separate bathroom and eating facilities for African-American employees. But in many cases it was simply not possible to create the physical infrastructure of segregation quickly enough or at all, a fact which lead to bizarre workarounds. According to W.E.B. Du Bois, in workplaces where black employees could not be separated from white employees because of the nature of the work, special cages were built for black employees within white workplaces. Really.

The effective segregation of the federal government continued in place for two decades before the tide began to shift in the 1930s under President Franklin Roosevelt.