I want to touch on something I’ve been thinking a lot about and have alluded to a few times. Just as we’re hearing more and more about ISIS and the threat it poses, we’re actually seeing more and more evidence that it is losing ground on its own turf. Let me start with two pieces in The Washington Post in the last couple days.

First, “In campaign against terrorism, U.S. enters period of pessimism and gloom.“

The piece starts with this …

U.S. counterterrorism officials and experts, never known for their sunny dispositions, have entered a period of particular gloom.

In congressional testimony recently, Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper Jr. went beyond the usual litany of threats to say that terrorism trend lines were worse “than at any other point in history.”

Down into the piece though there’s this.

Officials emphasize that their campaign has accomplished critical goals. In particular, most officials and experts now see the risk of a Sept. 11-scale attack as infinitesimal, beyond the reach of al-Qaeda and its scattered affiliates.

This is a pretty major qualification.

Of course, there are ways in which this is not a contradiction. Terrorism poses other dangers beside mass casualty attacks within the US. And I suspect they are also saying, correctly, that it might take years or a decade or even a generation to fully incubate another cohort of fighters who might later launch such attacks.

Still it’s a very, very big qualification.

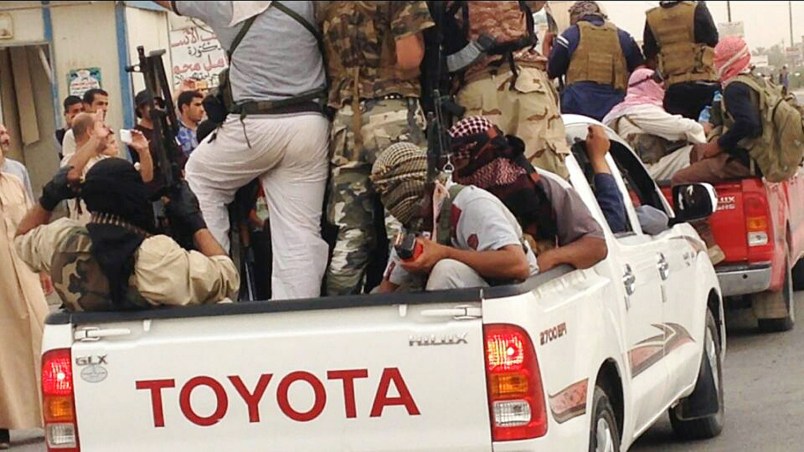

Then there’s ISIS on the ground in Iraq and Syria. We’ve seen various reports of this on battlefield reverses, but this piece (also in the Post from a day later) looks at another dimension – “Islamic State appears to be fraying from within.” It’s not a secret that ISIS has lost ground on several fronts in recent months in Iraq and Syria. This is especially though not exclusively in areas where there is religious or ethnic heterogeneity – particularly in Kurdish areas. This article explains both the battlefield reverses and internal disaffection within the area of ISIS control.

Most interesting is the feedback loop between battlefield reverses and recruitment. ISIS’s greatest propaganda tool is its own territorial existence — and its success. If it stops succeeding, if it starts giving up ground, that takes the glow off its millennial halo. Also notable in this piece are supposed fissures between native Syrians and Iraqis and foreign fighters who have rushed in from countries around the world. According to this story, a lot of the foreign fighters aren’t actually doing a lot of the fighting but are just setting up in a few ISIS-ruled cities —like a jihadist Disneyland — while the locals are out on the peripheries of ISIS control, prey to Kurdish militias, US airstrikes and defeat.

It’s hard to get a clear sense of all these particulars. But the larger point is important: We’re hearing lots and lots of information that things are not going well for ISIS. There is internal discontent. They are experiencing battlefield setbacks. Indeed, there is a good deal of evidence that upping the ante in brutality in the execution videos — which has driven so much of the perception and the politics in the US — has been geared to trying to offset battlefield setbacks. And yet — while it’s mainly in the open if you’re paying attention — little of this has made its way into the ISIS narrative.