In True the Vote’s complaint, it asks for review of the poll books (looking apparently for voters who both voting in the Democratic primary a few weeks earlier and the Republican primary). I agree that if the campaign (or True the Vote or someone else) could show that more than 6,700 people voted in both primaries, that could be grounds for a court to order a new election in the #MSSEN Cochran-McDaniel case. (So far I have not seen public evidence of the alleged thousands of such voters already uncovered.)

But I don’t see that True the Vote’s argument is likely to succeed for examination of poll books under the NVRA (motor voter). Here is the relevant provision:

Section 8(i)(1) of the NVRA provides:

Each State shall maintain for at least 2 years and shall make available for public inspection and, where available, photocopying at a reasonable cost, all records concerning the implementation of programs and activities conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters, except to the extent that such records relate to a declination to register to vote or to the identity of a voter registration agency through which any particular voter is registered. 42 U.S.C. 1973gg-6(i)

Here’s True the Vote’s argument that poll books count under this statute:

34. Poll books—the records at issue in this case—mirror the state’s voter registration rolls. They are records “concerning the implementation of programs and activities conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters.” 42 U.S.C. § 1973gg-6(i)(1); see Project Vote/Voting for Am., Inc., 682 F.3d at 335. Meanwhile, the process of reviewing completed voter materials, such as poll books, constitutes a “program” or “activity” evaluating voter records “for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters.” See Project Vote/Voting for Am., Inc. v. Long, 682 F.3d 331, 335 (4th Cir. 2012). Accordingly, the records made the basis of this case are subject to the NVRA.

I don’t see this as a strong argument. To begin with, textually, poll books are not records of voterregistration or “programs and activities” for insuring the accuracy of registration; they are records ofvoting. Further, examination of the poll books under True the Vote’s theory of double voting would not show if people were properly registered; it could show that people voted improperly.

Finally, the sole case that True the Vote relies on here, ironically a Project Vote case (it is ironic because Project Vote had a relationship with ACORN, a True the Vote Satan), does not contain any support for the idea that poll books are covered by this section of the NVRA. The Project Vote case concerned that group’s attempt to examine rejected voter registration applications. Here is the specific discussion from the case that True the Vote cites in its complaint:

Finally, as explained above, Section 8(i)(1) of the NVRA mandates public disclosure of voter registration activities. Id. § 1973gg–6(i)(1). It generally requires states to “make available for public inspection and, where available, photocopying at a reasonable cost, all records concerning the implementation of programs and activities conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters.” Id. This language embodies Congress’s conviction that Americans *335 who are eligible under law to vote have every right to exercise their franchise, a right that must not be sacrificed to administrative chicanery, oversights, or inefficiencies. Under the district court’s interpretation, this provision mandates disclosure of the records requested by Project Vote.

III.

A.

1 We begin by considering the Commonwealth’s argument that the text of Section 8(i)(1) does not require public disclosure of completed voter registration applications. This issue of statutory interpretation is one that we review de novo. United States v. Ide,624 F.3d 666, 668 (4th Cir.2010). The starting point for any issue of statutory interpretation is of course the language of the statute itself. United States v. Bly, 510 F.3d 453, 460 (4th Cir.2007). “[W]hen the words of a statute are unambiguous, … this first canon is also the last [and] judicial inquiry is complete.” Willenbring v. United States, 559 F.3d 225, 235 (4th Cir.2009) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Appellants assert that “[t]he plain and ordinary meaning of [Section 8(i)(1) ] does not encompass voter applications, much less the rejected applications initially sought.” Appellants’ Br. at 10. Instead, they claim, the “ ‘programs and activities’ referred to in Section 8(i)(1) of the NVRA are programs and activities related to the purging of voters from the list of registered voters.” Id. at 11.

Contrary to appellants’ insistence, the plain language of Section 8(i)(1) does not allow us to treat its disclosure requirement as limited to voter removal records. As the district court concluded, completed voter registration applications are clearly “records concerning the implementation of programs and activities conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters.” 42 U.S.C. § 1973gg–6(i)(1).

First, the process of reviewing voter registration applications is a “program” and “activity.” Under Virginia law, election officials must examine completed voter registration applications and register applicants that possess the necessary qualifications. See Va.Code § 24.2–417. This process of review is a “program” because it is carried out in the service of a specified end—maintenance of voter rolls—and it is an “activity” because it is a particular task and deed of Virginia election employees.

Moreover, the “program” and “activity” of evaluating voter registration applications is plainly “conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters.” 42 U.S.C. § 1973gg–6(i)(1). It is unclear what other purpose it would serve. As the district court reasoned, the process of reviewing voter registration applications keeps official voter lists both “accurate”—free from error—and “current”—most recent. See Project Vote, 752 F.Supp.2d at 706. Indeed, voter lists are not “accurate” or “current” if eligible voters have been improperly denied registration or if ineligible persons have been added to the rolls. Id. By registering eligible applicants and rejecting ineligible applicants, state officials “ensure that the state is keeping a ‘most recent’ and errorless account of which persons are qualified or entitled to vote within the state.” Id. Accordingly, the process of assessing voter registration applications is a “program[ ] and activit[y] conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters.” 42 U.S.C. § 1973gg–6(i)(1).

Furthermore, the registration applications requested by Project Vote are clearly “records concerning the implementation *336 of” this “program[ ] and activit[y].” Id. The requested applications are relevant to carrying out voter registration activities because they are “the means by which an individual provides the information necessary for the Commonwealth to determine his eligibility to vote.” Project Vote, 752 F.Supp.2d at 707.Without verification of an applicant’s citizenship, age, and other necessary information provided by registration applications, state officials would be unable to determine whether that applicant meets the statutory requirements for inclusion in official voting lists. Thus, completed applications not only “concern[ ] the implementation of” the voter registration process, but are also integral to its execution.

Finally, “the fact that [Section 8(i)(1) ] very clearly requires that ‘all records’ be disclosed brings voter registration applications within its reach.” Id. at 707–08(emphasis added). As this court has recognized, “the use of the word ‘all’ [as a modifier] suggests an expansive meaning because ‘all’ is a term of great breadth.”Nat’l Coal. for Students with Disabilities Educ. & Legal Def. Fund v. Allen, 152 F.3d 283, 290 (4th Cir.1998). Given that the phrase “all records concerning the implementation of programs and activities conducted for the purpose of ensuring the accuracy and currency of official lists of eligible voters” unmistakably encompasses completed voter registration applications, such applications fall within Section 8(i)(1)’s general disclosure mandate.

Perhaps True the Vote will have stronger arguments as they brief this case. But so far this appears weak to me.

This post was originally published at Election Law Blog.

Professor Richard L. Hasen is Chancellor’s Professor of Law and Political Science at the University of California, Irvine. Hasen is a nationally recognized expert in election law and campaign finance regulation, and is co-author of a leading casebook on election law.

—

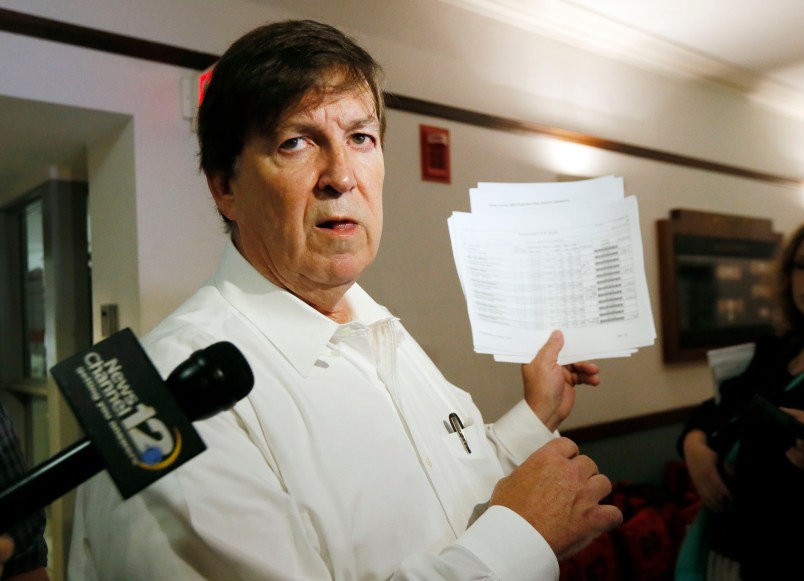

Photo: Hinds County Republican Party chairman Pete Perry holds an example of a sheet from the Democratic poll book in Hinds County that showed three voters as having voted in the Democratic primary June 3, but that notation being crossed out and the correct mark being made in the June 24 column, during a news conference at the Hinds County Courthouse in Jackson, Miss., Friday, June 27, 2014. Perry said claims of voter fraud cited by the tea party and state Sen. Chris McDaniel’s campaign for the Mississippi GOP U.S. Senate nomination are simple clerical errors that were fixed. McDaniel lost to the incumbent U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran, R-Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)