Tuesday night’s primary election in North Carolina set up a critical Senate race this fall – one that could not only decide who controls the Senate, but offers a perfect illustration of the ideology that’s increasingly driving our political debate, even if it goes mostly unmentioned.

To explain why, let me start with Eric Cantor.

Rep. Eric Cantor (R-VA) opposes an extension of unemployment insurance benefits despite a still-rocky jobs situation, yet he wants to extend a set of expiring tax cuts. Danny Vinik at the New Republic calls this hypocritical: Cantor insisted that UI extension be paid for to eliminate any deficit impact, but doesn’t insist on the same for extending tax cuts.

But the only hypocrisy here is if you actually believe what Cantor is saying about why he opposes the UI extension.

The baseline value here has zero to do with deficits, and everything to do with who “deserves” our help. Cantor is coming from a standpoint that you shouldn’t punish the “winners” in the business community with taxes and you shouldn’t reward the “losers” with unemployment insurance.

Republicans get in trouble when they say this explicitly, because it’s not a particularly widespread worldview. So Cantor has to pretend his opposition to extending unemployment insurance is about deficits, even when the argument crumbles when you compare it to his other priorities.

The standpoint that you can divide the world into successful productive people and meritless moochers, that justice requires us to just get out of the winners’ way, and stop propping up the losers, is the underpinning to Republican economic policy, whatever their public arguments are.

Conveniently, this philosophy of upward redistribution is very appealing to the tiny sliver of wealthy people who can afford to fund campaigns, and whose priorities drive political debate.

A recent column by conservative writer Ben Domenech offers a perfect summation of this argument: “Why Inequality Doesn’t Matter.” Domenech says that the extreme economic inequality we see shouldn’t bother us, because market outcomes are determined by “your own knowledge, your own work ethic, and the quality of what you produce,” and that the only possible counter-argument to this is jealousy, or that someone is unfairly using government as an artificial means to get more than they’ve earned.

In other words, yes, lawyers are more valuable than teachers, Donald Sterling contributes more to society than a night nurse at a VA hospital, and the fact that they make more money is in itself a symbol of their greater value and merit.

(Or, as the 1990s sketch comedy show “Mr. Show” put it, “a person who makes more money than you is better than you, and therefore beyond criticism!”)

Give Domenech credit for this: he isn’t making the bad-faith argument that all inequality can be traced to government; rather, he’s making his case explicit – that any inequality, no matter how extreme, that emerges from markets is a reward for virtue and merit, and the only kind of inequality we should worry about at all is that some people get help from the government.

It’s a remarkably straightforward, honest, and clear reaction to the growing concern about extreme economic inequality in the U.S. It’s what lies beneath Eric Cantor’s apparent hypocrisy on unemployment insurance and tax extenders.

(By the way: be wary of people who claim that “government causes inequality.” They are trying to use the genuine concern about economic inequality to get you to buy into the worldview described above. It’s a less honest version of Domenech’s argument.)

Which brings us to Thom Tillis.

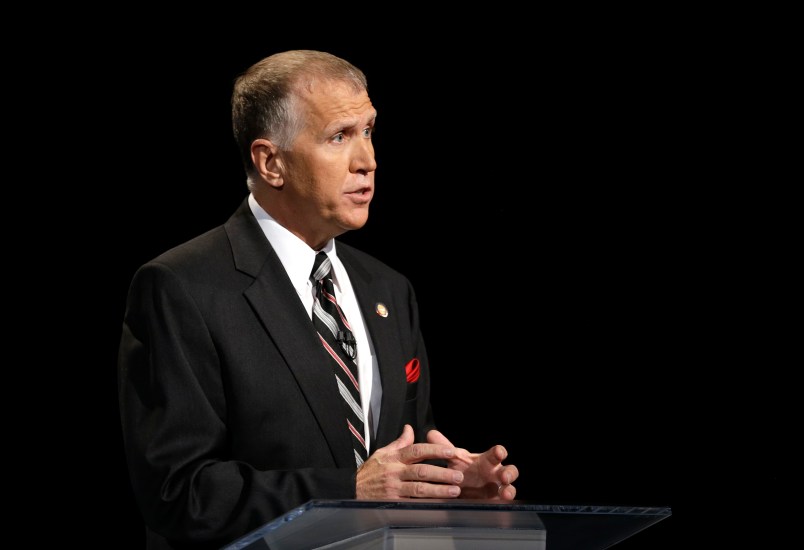

This week Tillis won the Republican primary for the right to take on Democrat Sen. Kay Hagan in what I’d argue is the key race for control of the U.S. Senate. Tillis, the speaker of the North Carolina state House, has a decent chance of becoming a U.S. senator next year – and he’s a poster boy for the policy agenda that naturally comes from the producers-versus-looters mindset.

Getting the most attention right now is a video from 2011, in which Tillis said “we need to divide and conquer people on public assistance,” drawing on the fable advanced by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) and others that most people on public assistance don’t really “deserve” the help and are choosing to become dependent on it because they are deficient culturally. Greg Sargent of the Washington Post compared these comments to Mitt Romney’s infamous “47%” video, and rightly so.

But his “divide and conquer” comments are just words. He doesn’t just talk this upward-redistribution philosophy: he lives it. As speaker of the House, he is perhaps the most important figure in turning North Carolina into a test lab for right-wing policy:

The changes to voting rights, taxes, Medicaid, and unemployment insurance are very much about who “deserves” basic things like democracy and economic security. “Winners win and losers lose” is a perfect way to justify policies that widen economic inequality. Tillis’ actions have made it very clear where he stands, more than any video could.

After his victory this week, while speaking to Chuck Todd on MSNBC, Tillis said that he regretted the wording of his “divide and conquer” remarks. I’m sure he does regret the words. It would be more meaningful if he regretted the philosophy behind his remarks, the philosophy that justifies the policies he’s pushed in North Carolina.

Now he wants to be yet another voice for that worldview in Washington.

Seth D. Michaels is a freelance writer in Washington, D.C. He’s on Twitter as @sethdmichaels.

This is a straight-up recapitulation of social Darwinism, formulated 130 years ago.

Of course - today’s Republicans deny essentially all science, and evolutionary science most of all, so they cannot use Darwinism as the foundation of their argument - so they cast it in moralistic terms.

If people are poor it is because they are immoral - lazy, wasteful, and willfully refusing to take “personal responsibility and care for their lives”. If you are rich it is because you are bursting with virtues of every sort, and for no other reason.

But back then, as now, it was all just white-wash to justify policies to enthrone the oligarchy of the rich over the economy and society as a whole.

As Eric Alterman notes in his review of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty’s book on the politics of inequality:

And rest assured that demonstrable bullshit, ideological assertion, and meaningless cliché are more addictive than crack to the villagers.

It’s a damn shame but the fact is Tillis is appealing to the worse natures of some (not all) North Carolinians by breaking down which group of poors deserves help and which does not. It makes some of those citizens feel secure and righteous that they helped the "right ones."It makes no difference whatsoever that there’s no evidence that there’s a substantial group of poors that are undeserving of help. This is a concept that some people “just know.”

“Politics of Inequality” presume we are all equal but all equal we are not.

The capitalist version of “Might Makes Right”

By this very thinking, the national IQ dropped significantly in the “Greatest Generation”. Income inequality would have been much greater had not an entire generation of Americans not been such a mediocre bunch that seemed to lack the ability to distinguish themselves in any significant way economically. If it weren’t for the rest of the world economy being in the shambles following the Great Depression and WWII, then the US would have essentially continued to be viewed as a Third World country, or a minor power at best. Assuming, of course, that the increase in income inequality can be tied to actual merit.