The recent attacks on military and law enforcement personnel in Canada and the U.S. raises the specter of “lone wolf” terrorist attacks, making Muslims suspect. Such thinking is superficial and reactionary. In the age of modern Islamophobia, it is a situation of owning a hammer and thinking everything is a nail. Looking at so-called “lone wolf” attacks in more detail and in a larger context reveals disconcerting issues in mental health care and media representations of Islam.

After 9/11, during the height of American anxiety about Al-Qaeda, significantly more Muslims (and people believed to be Muslim) were attacked in America than were harmed by “lone wolf” attacks in the U.S. This mirrors an international trend in which terrorists acting in the name of Islam kill more Muslims than any other group of people. Domestically, the majority of terrorist plots are thwarted by other Muslims. Even with this data from military and intelligence agencies, Rep. Peter King (R-NY) decided to hold congressional hearings in 2011 attempting to show that American Muslims were a suspect group. Now, with the rise of Daesh – ISIS/ISIL gives them a legitimacy they do not deserve — the same pattern of treating Americans as traitorous is repeating itself. This includes King, who has admitted to supporting more terrorist organizations than any Muslim he can find, once more calling mosques incubators of radicalization.

This bombast and ignorance not only demonstrates a lack of qualification to be chair of the House Homeland Security Committee, but also marginalizes a relatively well-integrated community and creates the problem he cannot otherwise find.

King’s hearings, while deeply concerning from a national security and civil rights perspective, is also emblematic of the popular media narrative of what it means to be Muslim. Edward Said, in his nearly 35-year old work Covering Islam, discussed the ways in in which which representation of Islam and Muslims in American media had nothing to do with the reality of Muslims, but with the political goals of those who deploy generic, baseless descriptions. These descriptions are damaging on multiple levels. They prevent critical examination of key issues by using simple narrative devices. They valorize the rhetoric of groups like Al-Qaeda and Daesh as being true, without any reference to what most Muslims believe and do. The rise in Islamophobia, and the concurrent rending of America’s social fabric, is another consequence. Finally, because of the power of American media, these descriptions even define the religion for Muslims. Using contemporary examples, Wolf Blitzer and Google have as much an impact as Yusuf al-Qaradawi or Ali Sistani.

We know that anti-Muslim rhetoric is correlated to hate crimes, no matter where that rhetoric is produced. With the power of voices like Sam Harris and Bill Maher supporting Daesh’s view of Islam, David Horowitz writing thank you letters to Daesh, and Pam Gellar plastering Dash messaging all over the NYC subway system under the guise of being “pro-Israel,” it should come as no surprise that viewers begin to define Islam as Daesh does. This results in “converts” seeking out information on Islam and finding a religion that is defined as violent. In this context, converts are not only those who come to Islam from a different faith, but also those born as Muslim who seek to know about their faith, so British extremists buy books like “Islam of Dummies.”

The narrative of Islam that provides structure and answers through violence meshes with the desires of individuals who are marginalized, providing meaning they are otherwise lacking. Historically, we see similar phenomenon with Christianist movements, Marxism, white power groups, movies, and video games.

Religious symbols and language have also proven to be attractive to those suffering from mental illness. In addition to the sense of control that religion may shape, the acceptability of an unseen world and disembodied voices can give meaning to things in their lives that do not otherwise make sense.

With this background, the recent spate of individual attacks do not represent a growing threat from Daesh. Instead, they show how the paucity of understanding about religion keeps us from exploring deeper social issues. The Ft. Hood and Sandy Hook shooters were flagged for needing mental health interventions and the Ottawa shooter explicitly asked for an intervention.

No serious person would suggest that converts, as a group, are definitionally mentally ill, or that people with mental health needs are mostly violent. At the same time, the media representation of Muslim belief can attract that small intersection of mentally ill and violent individuals. The narrative, overall, appeals to those at the margins — socially, medically, economically— who want to find some type of control and power in their lives.

The uncritical repetition of Daesh’s propaganda has practical implications, and masks necessary conversations around domestic security. It is time to start putting more tools in the toolbox.

Hussein Rashid is a professor of Religion at Hofstra University, a term member at the Council on Foreign Relations, a Truman National Security Fellow, and a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. He works at the intersection of religion, art, and national identity.

—

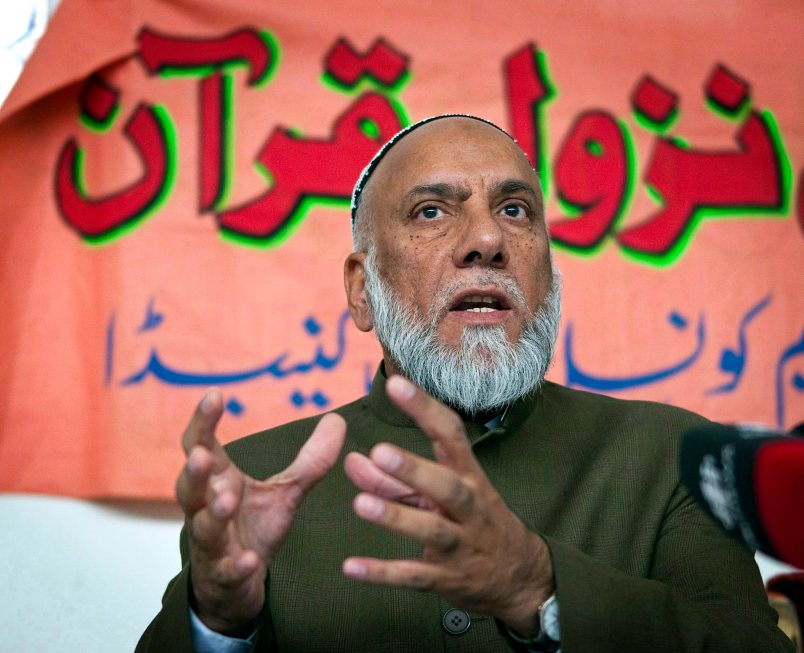

Lead photo: In this Aug. 31, 2010 file photo, Imam Syed Soharwardy, leader of The Islamic Supreme Council of Canada, speaks in Calgary. (AP Photo/The Canadian Press, Jeff McIntosh)

Very interesting. I hadn’t thought about the possibility that the American Media may be partially responsible for recruiting and radicalizing the mentally ill. But it certainly makes sense. Although a shout out to the Islamophobia channel, FoxNews might have been warranted.

Meh. I would readily aver that anti-muslim hate crimes are undercovered and wish that were not the case. But to suggest that coverage that asks whether any given new violent crime that initially has the trappings of an Islamist lone wolf might be just that is ridonculous. There is a sad but relatively un-newsworthy baseline of violent crime in this country by the mentally disturbed, just like there is a sad baseline of car crashes or gun accidents. If, on top of that, we begin to see–as we already have in Great Britain and Canada–incidents of American citizens activated to jihad by social media, sorry fella, but that’s news.

Religion is what people make it. You can use it for good, or for evil. The name of Jim Jones church was The People’s Temple of the Disciples of Christ.

The best way for the unfriendly coverage to end would be if Wahabbi sunnis did not commit acts of terrorism. It is hard to cover a beheading without social, cultural, educational and religious context.

Prof. Rashid’s argument has a corollary on the right, where they love to cite random statistics about black-on-black crime and the paucity of coverage thereof whenever a white cop or a gang of racists attack a black person.