This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published in 2015.

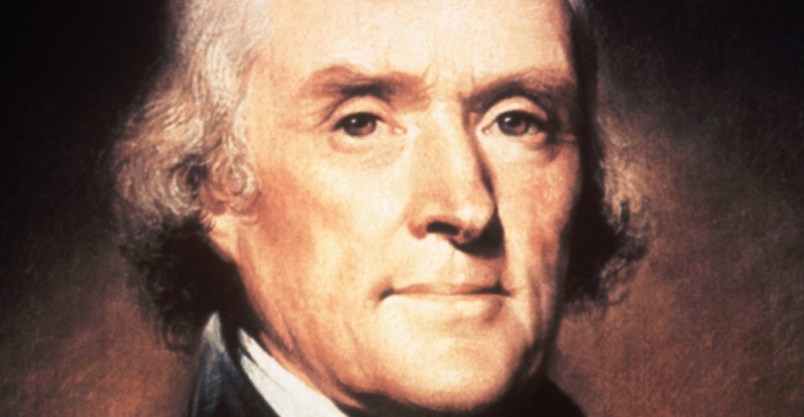

As with so many debates in our 21st century moment, the question of race and the Declaration of Independence has become a divided and often overtly partisan one. Those working to highlight and challenge injustice will note that Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration and its “All men are created equal” sentiment, was like many of his fellow founders a slave-owner, and moreover one who might well have fathered illegitimate children with one of his slaves. In responses, those looking to defend Jefferson and the nation’s founding ideals will push back on these histories as anachronistic, overly simplistic, exemplifying the worst form of “revisionist history.”

If we push beyond those divided perspectives, however, we can find a trio of more complex intersections of race and the Declaration, historical moments and figures that embody both the limitations and the possibilities of America’s ideals. Each can and should become part of what we remember on the Fourth of July; taken together, they offer a nicely rounded picture of our founding and evolving identity and community.

For one thing, Jefferson did directly engage with slavery in his initial draft of the Declaration. He did so by turning the practice of slavery into one of his litany of critiques of King George:

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation hither … And he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he had deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

Like so much in the American founding, these lines are at once progressive and racist, admitting the wrongs of slavery but describing the slaves themselves as “obtruding” upon and threatening the lives of the colonists. Not surprisingly, this complex, contradictory paragraph did not survive the Declaration’s communal revisions, and the final document makes no mention of slavery or African Americans.

Yet the absence of race from the final draft of the Declaration did not keep Revolutionary-era African Americans from using the document’s language and ideals for their own political and social purposes. As early as 1777, a group of Massachusetts slaves and their abolitionist allies brought a petition for freedom based directly on the Declaration before the Massachusetts legislature. “Your petitioners … cannot but express their astonishment,” they wrote, “that it has never been considered that every principle from which America has acted in the course of their unhappy difficulties with Great Britain pleads stronger than a thousand arguments in favor of your petitioners.”

When Massachusetts drafted its own state constitution in 1780, that document’s extension of the Declaration’s sentiments added more ammunition to such slave petitions. And so between 1781 and 1783, a number of court cases, including a trio focused on escaped slave Quock Walker, led Massachusetts courts to declare slavery illegal under that state constitution. With the Revolution and America’s political future still unfolding, these slaves and cases made clear that, elisions from the Declaration notwithstanding, the new nation’s ideals and actions would influence all of its communities.

The nation as a whole did not follow Massachusetts’ example in the aftermath of the Revolution, of course. Indeed, the Constitution solidified the legality of slavery by defining slaves as 3/5ths of a person for the purposes of state populations and political representations. Yet the debate over race and the nation’s founding ideals did not cease, and more than 75 years after the Declaration Frederick Douglass gave voice to the most impassioned and potent argument in that ongoing debate.

In his speech “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” delivered at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall on July 5th, 1852 and later renamed “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” Douglass lays into the hypocrisies and ironies of the occasion and holiday. “Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?” he inquires, adding “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

Yet as he did throughout his long career, Douglass weds such biting critiques to powerful arguments for the urgency of moving toward a more perfect union, one inspired by our national ideals. “I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope,” he concludes. “While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age.”

Those tendencies did indeed result in the abolition of American slavery, an abolition begun by the same president who once more called upon the Declaration’s moment and history in his famous “Four score and seven years ago” opening to the Gettysburg Address. Yet as recent events and tragedies have so fully reminded us, the debate over race and American identity and ideals, and the role of slavery within those histories, continues. As we celebrate the Fourth of July this year, we would do well to remember not only Jefferson and his cohort, but Quock Walker and his, each in their own vital ways part of the nation’s Revolutionary founding. And as we recite the Declaration’s opening, we should quote Douglass’s speech as well, and engage with what the holiday has meant and means for all our fellow Americans, past and present.

But happily [snark], they left IN the bit about the “merciless Indian savages.”

The line, “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration was taken from the Enlightenment’s Immanual Kant’s line about the rights all men have, “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of property.” Jefferson changed the line because, in 1776, the term “property” also meant slaves.

The Declaration of Independence was just that, a declaration, with symbolic but no binding legal value. That there was anti-slavery sentiment prior to the Revolution is not news. In fact, the Constitutional Convention a decade later was at loggerheads over the issue until the northern reps backed down for the sake of geographical unity of with the southern states in one nation. Hence, the slavery related clauses in the Consitution. Would have, could have, etc., don’t count in defining the social foundation of America as the home of slavery.

Actually “life, liberty, and the pursuit of property” comes from John Locke.

Especially considering that by 1772, Chief Justice Mansfield had declared slavery illegal in England and Jefferson and the founding fathers would surely have been aware of that.

In 1783 The English House of Commons debated a bill to abolish the human trade on moral grounds, and in 1833, Parliament outlawed slavery throughout the British Empire.