Chris Christie is in South Carolina this week, his first trip there in the 2016 cycle. On Tuesday he spent seventy minutes answering questions from GOP activists, road testing pro-gun, anti-Common Core, and anti-teachers’ union messages as he lays groundwork to enter an ever-widening pool of contenders for the GOP nomination.

It would seem that, for now, the postponement to mid-November of the Bridgegate trials of former Port Authority deputy executive director Bill Baroni and Christie’s former deputy chief of staff Bridget Anne Kelly works in Christie’s favor. The summer could allow him to regain national footing, and it wouldn’t be all that surprising if we see something of a Christie bounce.

But there is something going on in the pre-trial maneuvering that could turn into a real headache for the governor.

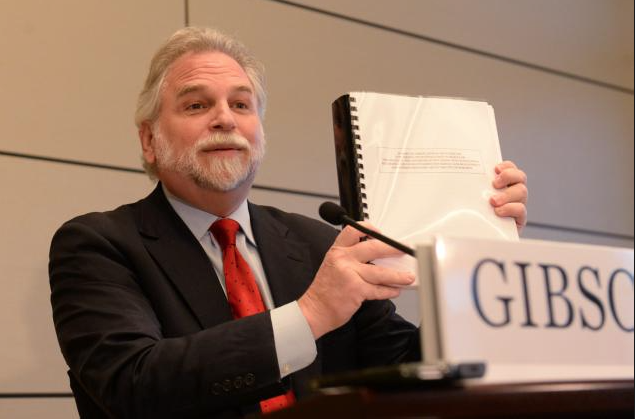

Last week, Bridget Anne Kelly’s attorney, Michael Critchley, filed a request with the presiding judge to be given the power to subpoena Gibson, Dunn, & Crutcher. That’s the law firm Christie hired last January – at public expense – to investigate his administration and produce the so-called “Mastro Report” that exonerated him from any culpability in both Bridgegate and allegations leveled against him by the Mayor of Hoboken relating to Hurricane Sandy relief aid.

Critchley wants to look at the work product – interview transcripts, notes, and so forth – to see what people actually said and whether they square with the final report. Only one problem: Gibson Dunn told Critchley those notes and other work product don’t exist.

Would that be a big deal? Yes. Yes it would. It would be a big deal for a number of reasons but the most immediate would be that Christie hired Gibson Dunn on the State of New Jersey’s dime.

The Mastro Report, which didn’t look or read like or conform to the standards of a conventional GAO-style investigative document, cost more than $3.5 million in taxpayer funds by the time it was released in March 2014. The firm billed the state more than $1 million during its first three weeks’ of work, then more than $2 million in February, causing a minor panic in the Christie administration as they saw a looming public relations disaster. The solution was to negotiate the firm’s hourly rate down from $650 an hour to $350 an hour.

But the work never ended.

So far, Gibson Dunn has been paid more than $7.75 million by the state of New Jersey to represent Christie and members of his administration in Bridgegate and related investigations. The vast majority of that money has been spent on the federal investigation led by U.S. Attorney for New Jersey Paul Fishman.

Gibson Dunn billed the state $53,824 in April, $37,731 in March, and $106,325 in February of this year. These fees cover witness interviews and document production – reviewing and handing over documents to prosecutors and investigators in response to subpoenas and less formal requests. A fuller picture of the nature of the firm’s work is obscured, however, by heavy redactions made by the New Jersey Attorney General’s office to the firm’s bills before they’re disclosed to the public each month, always late on Friday afternoons.

To put Gibson Dunn’s billings in perspective, Christie’s administration spent a total of $31 million on outside counsel in 2014. That means about 1 in 4 of those dollars went to Gibson Dunn.

If that total seems like a lot, it is; the figure is $2 million more than taxpayers spent on outside attorneys in 2013, and over $10 million more than what was spent in Christie’s first year as governor in 2010. In fact, on a year-over-year basis, Chris Christie’s administration has increased its spending on outside counsel in every year that’s passed since he assumed office.

At the time Gibson Dunn was hired to represent Christie in the Bridgegate investigation in early January 2014, the firm had already billed taxpayers $3.1 million in 2013 to represent New Jersey in a fight to legalize gambling on sporting events – a battle that is still ongoing.

Here’s where Bridget Anne Kelly’s lawyer wanting to subpoena Gibson Dunn comes into play.

With all that work under its belt, we can assume the firm was already familiar with the state’s manual of guidelines governing the standards and conduct of firms hired by the Office of the Attorney General as outside counsel.

This is important, because what Bridget Kelly’s attorney is asking the judge to subpoena are the notes and transcripts that Gibson Dunn’s attorneys used to draft the “Mastro Report,” the report which exonerated the Governor and tossed the now-indicted former associates under the proverbial bus. The report is named after the firm’s high-profile partner, Randy Mastro, who led the team that produced the document.

In the first months of 2014, Mastro and his team interviewed 75 witnesses, the vast majority of whom worked in the Christie Administration, to produce a 344-page report that, notably, went out of its way to awkwardly suggest that Bridget Kelly could have supported closing lanes on the George Washington Bridge because Bill Stepien, Christie’s former campaign manager, had broken off a relationship with her.

Now, Bridget Kelly’s attorney wants to see who said what in the interviews that were used by Gibson Dunn’s team to draw that conclusion, one of several in the report that insulated the governor while discrediting Kelly. According to Critchley, several witnesses questioned by Gibson Dunn reported that a paralegal or stenographer was present in the room “‘feverishly’ typing verbatim or near verbatim notes of everything that was said” during their interviews.

Yet according to Critchley’s filing with the court, the U.S. Attorney’s Office has told him that when they asked Gibson Dunn for those interview transcripts, they were told by the firm that none exist.

Now, there are three possibilities here. The witnesses could be lying. That doesn’t make sense. But it’s possible.

What’s more likely are one of two things: either Gibson Dunn has the notes, or they opted to destroy them at some point.

Both would be a real problem for Gov. Christie.

Let’s take the first.

During the legislative hearings that were held last spring and summer, several witnesses who’d been interviewed by Gibson Dunn told state lawmakers, under oath, that the Mastro Report mischaracterized what they recalled telling Gibson Dunn attorneys. Some even objected to conclusions drawn in the Report.

In one instance, Kevin O’Dowd, Gov. Christie’s former chief of staff and onetime nominee to be the state’s attorney general, faulted Gibson Dunn for failing to fully respond to a legislative subpoena in advance of his public testimony. He came to the hearing with his own personal attorney in attendance, but Gibson Dunn had been responsible for handling his document production in response to legislative subpoenas. And they didn’t turn over text messages to lawmakers that were mentioned and included in the Mastro Report, and which fell squarely within the scope of the legislature’s subpoena for Bridgegate-related text messages.

Did Gibson Dunn massage evidence to support a pre-determined conclusion that exonerates Christie?

If interview transcripts exist and repeatedly diverge from the narrative that was eventually laid out in the Mastro Report or the interview summaries, it raises the question of what Gibson Dunn has been doing with all that public money and why they were hired by Christie’s team in the first place.

Bringing in Randy Mastro in January 2014, after all, was hardly an effort to be cooperative with investigators. Mastro was brought in to both advocate on Christie’s behalf and also render a verdict on his guilt.

Before joining Gibson Dunn, Mastro was an Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Southern District of New York, serving under then-U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani. When Giuliani was elected mayor of New York in 1994, Mastro followed him, first as a deputy mayor tasked with driving the Mafia out of the Fulton Fish Market, and then as chief of staff in City Hall. When Mastro returned to Gibson Dunn he became the head of the firm’s litigation practice, handling a high-profile roster of corporate clients in big money cases.

[Not one for modesty, Mastro’s official biography page on Gibson Dunn’s website features an unattributed quote saying “You do not want to meet Randy down a dark alley. But you REALLY don’t want to meet him in a lighted courtroom.” (Emphasis in the original (!))]

Not long after Mastro and Gibson Dunn were hired by the administration, John Wisniewski, the co-chair of the special legislative committee probing Bridgegate, predicted that the firm would “be very careful about biting the hand that feeds them” so much legal work. Will the Report’s already-strained credibility come under further questioning and seem like a part of the same cover-up that Bridget Anne Kelly and Bill Baroni are answering for in court? Could the legislature decide to probe how Gibson Dunn has spent that $7.75 million? They sure could.

Let’s consider the second option: that Gibson Dunn deep-sixed the transcripts and notes. This may be far more problematic for the firm and Christie. Here’s why:

According to the manual for outside counsel that’s put together by the N.J. Attorney General’s office, “outside counsel shall” – not may or might, but shall – “retain pleadings, correspondence, discovery materials, deposition transcripts and similar documents and work product for a period of no less than seven years.”

Although this clipping is from the 2015 version of those guidelines, the policy isn’t a new one. Virtually identical language can be found in the state’s 2011 manual for outside counsel.

Gibson Dunn is therefore under a contractual obligation to keep any documents and notes relating to these interviews since they constitute “work product.” Moreover, they were legally obligated to keep that material since everyone in the country knew in 2015 that Bridgegate was the subject of a federal grand jury investigation. Gibson Dunn is a firm packed with former federal prosecutors. They know these rules.

And note also that if anything was to be destroyed by the firm – even if it was after the ordinary seven-year-long retention period – Mastro’s team was obligated to notify their client – the Christie Administration.

The hiring of Gibson Dunn by the Christie Administration was always problematic. One of the attorneys who worked on the Mastro Report, Debra Yang, was, like Christie, a fellow George W. Bush-appointed U.S. Attorney. She’d vacationed with the Christies and was called a “good and dear friend” by the governor in 2011. She also billed 118 hours in the first month Gibson Dunn was brought aboard to defend her friend.

If the judge agrees that the transcripts are material to Bridget Kelly’s defense, Gibson Dunn’s legal bills, interview memos, and their compliance with their state contract are all likely to become the target of scrutiny. And if it turns out that Gibson Dunn did indeed destroy documents, Critchley is asking the judge to convene a hearing so he can ask who at the firm did the shredding, when it took place, and who in the Christie administration gave their approval.

My bet is that we’re going to be hearing a lot about the Mastro Report again – a document that was supposed to distance the governor from the trials that will unfold this fall. That distance may soon become uncomfortably small.

UPDATE: 3:35 PM on Thursday June 4, 2015:

This afternoon U.S. Attorney Paul Fishman’s office sent a letter to the judge presiding over Bridget Anne Kelly and Bill Baroni’s trials supporting Kelly attorney Michael Critchley’s motion to subpoena recordings, transcripts, and notes taken during witness interviews with Gibson Dunn attorneys representing the Christie Administration.

In the letter, Fishman’s deputies wrote that “without prejudice to the United States’ ability to challenge the admissibility of any such materials at trial or to challenge any subsequent defense motion under Rule 17 to compel the pretrial production of witness statements or impeachment material, the United States does not object to the issuance of the subpoena for the materials” requested.

Brian Murphy is a history professor at Baruch College who writes about the intersection of money and politics. You can follow him on Twitter @Burrite and find him at brianphillipsmurphy.com.

I have always thought, and will continue to think, this entire case is going to blow up on Christie in a big, ugly way. Perhaps not all at once, but things continue to drip out like a leaky faucet and he has no way to contain it short of “offing” people.

A huge number of people involved in this are lawyers. Many of them active practising lawyers. I have serious doubts they are going to risk their future ability to practice law to protect Christie much longer. There are limits even to solicitor/client privilege, especially when that privilege has been paid for with taxpayer funds.

Bridget Kelly and David Weinstein have no incentive any longer to stay quiet. Neither does Stepien. While I have no respect for Kelly or what she was involved in, her lawyer is no dummy by taking this course of action. He’ll never completely exonerate his client…but he’s going to damn well make sure those who were giving the orders are going down with the ship.

I can’t WAIT for disclosure/discoveries on this one!

Do the ursine defecate amidst arboreal splendor?

The truth always has a way of coming back to bite you. I think this will be a big, big problem for Christy. Destroying records looks pretty fishy, and if true maybe we will see some jail time for somebody at this law office.

It seems that Christie and his gang of crooks are now hoisted by their own petard.

I suspect Rachel Maddow will be on the story tonight.