Numerous stories over the past months have reported that the Israeli government is indirectly negotiating a long-term ceasefire agreement with Hamas, the Islamist militant group that rules the Gaza Strip. First reported in May by leading Israeli security journalist Amos Harel, last week it was revealed that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who recently stepped down as Middle East “Quartet” envoy, had served as a point of contact for the talks. In exchange for a long-term truce, Israel would significantly ease the siege that has strangled Gaza for nearly a decade, which has been a key demand of Hamas and a condition of past cease-fire agreements ending previous rounds of fighting, though one that has never been implemented.

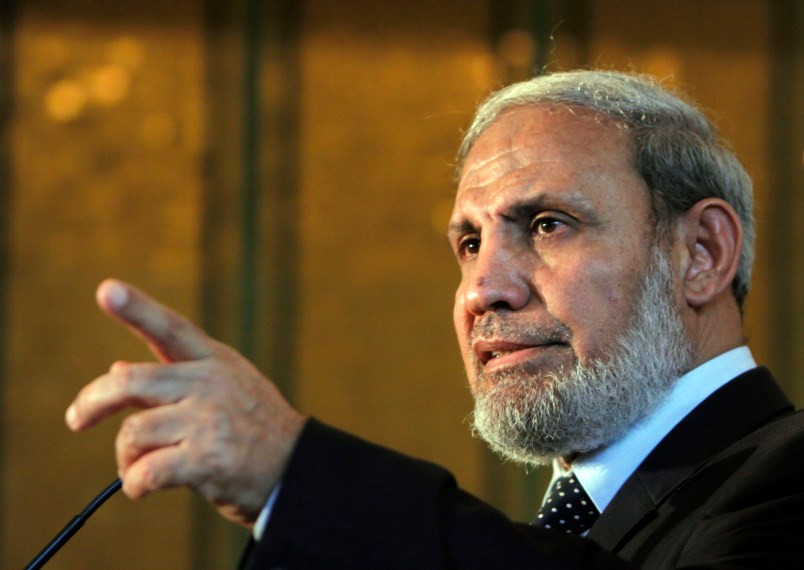

The Israeli government has consistently denied that any such negotiations were taking place. Hamas leaders have given contradictory statements; Hamas political chief Khaled Meshaal said last week that the negotiations looked “positive,” whereas Hamas co-founder Mahmoud Zahar has denied the negotiations existed at all.

It’s important to understand these statements in light of Meshaal and Zahar’s positions within the broader Hamas movement. Meshaal is the head of the group’s political wing, seen as a relative moderate within the group, and based outside of Gaza, in Doha, Qatar. Zahar, on the other hand, is based in Gaza, and therefore more exposed to the political pressures that such an agreement could create. He is seen as a hardliner, much closer to Hamas’ military wing, the Qassam Brigades, anhas also been a key point of contact with the Iranian government, which has given support to Hamas over the years. The Hamas-Iran relationship soured over Hamas’ decision to cut ties with Syria’s Bashar al-Assad government, a key Iranian ally, back in early 2012 in response to Assad’s violent suppression of demonstrations.

Within Gaza itself, there’s been an ongoing competition between the political and military wings, with the latter steadily increasing its power on the ground. When I visited Gaza in March of this year, the overwhelming consensus among those I spoke with was that the Qassam Brigades are essentially calling the shots there now.

Then there is the competition between Hamas and its Palestinian rival Fatah, which dominates both the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the internationally recognized body of the Palestinian national movement, and the Palestinian Authority, which exercises a small measure of autonomy in the West Bank under Israeli occupation. Having won the 2006 Palestinian elections, Hamas took control of Gaza in a short but violent civil war in 2007. (Hamas caught wind of a Bush administration-backed Fatah coup attempt in the works, and struck first.)

An agreement with Israel, then, would benefit the Hamas political leadership in two ways: first, against the increasingly powerful military wing, and second, against the moderate leadership of Fatah in the West Bank, where Hamas continues to be severely repressed. The first of these would probably be beneficial to the prospects of long-term peace and security. The second would almost certainly not be.

The deal as reported would significantly ease the blockade on Gaza, possibly by providing for the opening of a seaport, which has long been a key Hamas goal. The group has been under intense internal pressure since last summer’s devastating war with Israel in which more than 2,000 Palestinians were killed, the large majority of them civilians. Reconstruction has been almost nonexistent. As the New York Times reported last week, not a single one of the nearly 18,000 homes destroyed or damaged in the 51-day conflict is currently habitable.

Gazans blame both Fatah and Hamas for the lack of reconstruction. Fatah, under the leadership of President Mahmoud Abbas, has sought to address his political deficit through (largely symbolic) efforts in the international arena, such as UN recognition and membership in the International Criminal Court. He is not at all anxious to retake control of Gaza — an Israeli condition for reconstruction aid — and reproduce the situation he currently has in the West Bank, which is a lot of responsibility without any real power.

But any agreement that further solidifies the division between the West Bank and Gaza—which has been one goal of the Israeli blockade policy—would have hugely negative implications for prospects of ending the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israeli analyst Gershon Baskin, who helped negotiate with Hamas the release of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, sees an Israel-Hamas agreement as disastrous for Israeli-Palestinian peace. “Hamas is prepared to maintain a long-term ceasefire with Israel in exchange for Israel opening up Gaza and ending the economic siege. All that Hamas is willing to give in exchange is that it will not shoot rockets at Israel,” wrote Baskin. “At the same time, Hamas will continue to work against Palestinian moderates who are willing to negotiate with Israel. It will work to take over the West Bank.”

An Israel-Hamas agreement would also further reveal the emptiness of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s rhetoric about Hamas. A year ago, in the wake of last summer’s devastating war on Gaza, Netanayahu attempted to rally international opinion by insisting “Hamas is ISIS, ISIS is Hamas.” The comparison was dismissed by serious Middle East analysts, but dutifully echoed by Netanyahu’s supporters in Washington. Netanyahu and his allies also viciously attacked Abbas when he signed an agreement with Hamas earlier in the summer creating a transitional consensus government, saying that Abbas could have peace or an agreement with Hamas, but not both. “Whoever chooses the terrorism of Hamas does not want peace,” Netanyahu said at the time.

It’s also important to understand Gaza as an arena in which broader regional conflicts are being played out. The last few years have been pretty devastating for Hamas, especially compared to how they assumed it would go for them. When I visited Gaza in February 2012, Hamas leaders who I spoke to were confident that the Arab Spring would create an “Islamic awakening” that would usher them into power.

The next few years proved otherwise, as regional authoritarian regimes cracked down hard on Islamist groups, culminating in the July 2013 Egyptian coup, in which the military removed President Mohammed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, from power and undertook a series of violently repressive measures which have continued to today. The Egyptian government has destroyed the vast majority of smuggling tunnels on Gaza’s southern border with Egypt, removing a major source of tax revenue for Hamas and putting them in dire financial straits. This was a major factor in Hamas decision to seek reconciliation with Fatah in April 2014, in the hopes that Fatah would provide a source of revenue for civil workers. That agreement now appears to be going nowhere, like many before it.

Meshaal’s recent visit to Saudi Arabia, however, indicates that a shift in Saudi policy may be underway, part of a broader Saudi effort to bring Islamist groups under its Sunni umbrella in the regional struggle against Shia Iran. “[The Saudi] strategy is to unite as much as possible of the Sunni Middle East (excepting extremists like the Islamic State and Al Qaeda),” wrote analyst Hussein Ibish. “Riyadh may be right that this is the best way to strengthen its hand against Tehran’s cohesive Shiite bloc. But it also means consolidating already sharp sectarian divisions in the Middle East.”

With all of this in mind, some analysts remain deeply skeptical of the prospects of an agreement between Israel and Hamas. “I think the reports [of an agreement] are exaggerated, frankly,” said Mark Perry, a foreign affairs analyst with many years of experience in the Middle East. “There’s a real gulf between statements from Hamas and the Israeli government on this. My sense is that the hardliners in Gaza don’t have an indefensible position. Why are the Palestinians negotiating the end of the siege with Israel? It’s starving people, and the Gaza leadership just doesn’t trust Israel to keep any of its agreements, and they are justified in that. Meshaal understands that, but he also thinks that if he can come to agreement with Israel without compromising his long-term goals, then he’s fine with that.”

A new report from the widely respected International Crisis Group is also skeptical of the prospects for a longterm cease-fire (the report sees a new outbreak of violence as more likely). If an agreement were in the offing, however, it recommends including steps to address the Gaza-West Bank division. “To alleviate concerns about the consequences for Palestine writ large, any future Hamas-Israel agreement should include declarative statements that Gaza remains an integral part of a future Palestinian state and measures that strengthen currently weak Gaza-West bank connections, including more exports from Gaza to the West Bank and increased Gaza-West Bank travel.”

One drawback of an Israeli agreement with Hamas is that it would likely affirm, in the minds of both Hamas leaders and many Palestinians, Hamas’ use of violence, and further discredit Fatah’s nonviolent diplomacy. Many Hamas leaders remain convinced that their violence is what forced Israelis to withdraw from Gaza in 2005, a belief reinforced by Israel’s decision not to coordinate the withdrawal with Abbas. While Israel certainly has a legitimate interest in stopping rocket fire from Gaza, it’s hard to see the wisdom of furthering such a conviction among Hamas leaders that such violence works.

One thing Hamas’ political leadership craves, perhaps more than anything, is international legitimacy. A longterm agreement with Israel could give them that, and could provide Israel with calm, but very likely at the cost of pushing a final, conflict-ending agreement much farther down the road.

Matthew Duss is the president of the Foundation for Middle East Peace. His writing has appeared in numerous publications, including the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, the Nation, Foreign Policy, Politico, the American Prospect, and Democracy. He appears regularly as a commentator on radio and television.

What’s the typical historical evidence on whether official renunciation of violence precedes successful negotiations or follows them?

Israeli negotiation tactic: “The beatings will continue until moral improves.”

Yeah. That will work.

Thought-provoking information. Thanks for the article.

So it’s okay for Netanyahu to negotiate with Hamas but not okay for Obama to talk to Iran? Got it.

what a goddamn clusterfuck. It drives me up the wall whenever some Israel fanboy or fangirl starts pushing the “Israel good, Palestinians bad” propaganda. The entire thing is hopelessly complicated, carefully-nurtured grudges going back years and decades all around, radicals on all sides who are all too happy to destroy any sort of peace agreement for their own exceedingly narrow aims, and absolutely nobody is honorable nor has clean hands in the whole mess. At least the Israelis have proven they can govern themselves while the Palestinians probably couldn’t get their shit together long enough to govern so much as an HOA properly.