Schools throughout the country have made the musical “Into the Woods,” now a Disney movie, a perennial favorite—to the point that, according to NPR, “it’s currently the 3rd most popular high school show in the country.” They usually perform a “junior version,” though, one that that features Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, and other fairy tale favorites, and ends at intermission to avoid the potentially controversial sex and death. Yet sex and death are at the heart of the show, not merely its second act, for a reason: Stephen Sondheim, a gay man working in theater in New York City, created the show in the eighties at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

The show explores the consequences of going after, and getting, what one wants. I wondered how Disney would handle its more sophisticated elements, the losses and the betrayals. Would the family-friendly studio present the junior version, heavy on the fairy tales and light on the consequences, or would it give its audiences the grim—not to say Grimm—version Sondheim intended?

After all, long before Disney turned them into ways to sell toys, fairy tales were cautionary tales, often told by older women to younger ones to teach them about the dangers of the world. The original Grimm Brothers versions are violent, even cruel, for a reason: They are intended to instruct in a visceral way, through fear. In “Into the Woods,” Sondheim was merely matching his material to his times.

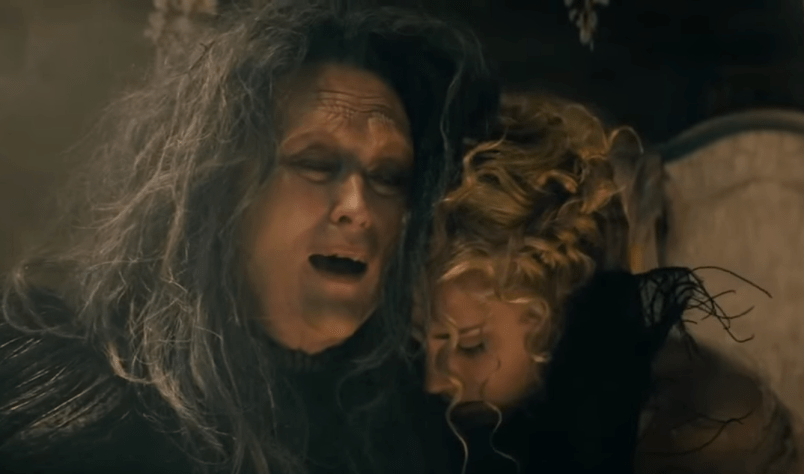

In the show’s first half, we meet our heroes—Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack (of beanstalk fame), two princes, a witch, and a baker and his wife—all of whom have a wish, and a reason to journey into the unknown to get it. The characters are plucky, independent, and appealing; although they commit various sins in order to reach personal fulfillment, we root for them and want them to succeed. And they do. They get laid, get married, get pregnant, get rich. Yet, after the curtain rises on Act Two, they (and we) learn that unintended consequences descend even on those who don’t deserve them.

The princes who secured the women of their dreams—Cinderella and Rapunzel, respectively—discover that marriage does not curtail the desire for more. The witch who got her youth and beauty back discover that they came at the expense of her powers. And the wife of the giant Jack killed returns, bellowing for blood. By the show’s end, the community has been worse than decimated. Almost no one remains, and those who do must band together, seeking strength from each other, to survive and gain the courage necessary to raise the next generation.

Some critics object to the dark turn “Into the Woods” takes after intermission. Frank Rich, reviewing the show when it originally debuted for the New York Times, called it “painful, existential” and, though promising and in parts brilliant, ultimately “disappointing.”

In Act II, everyone is jolted into the woods again—this time not to cope with the pubescent traumas symbolized by beanstalks and carnivorous wolves but with such adult catastrophes as unrequited passion, moral cowardice, smashed marriages and the deaths of loved ones.

Some institutions describe the show in straightforward terms as being “originally written in 1987 in response to the AIDS crisis.” Other critics, like Slate’s Dana Stevens, merely suggest that it reads “to many audience members as a metaphor for the AIDS crisis.” Sondheim himself has demurred, parrying the question: “We never meant this to be specific. The trouble with fables is everyone looks for symbolism.”

True—and a person as smart as Sondheim knows that fables are intentionally symbolic. If Cinderella were merely one girl, what relevance would her story have over centuries? But Sondheim has also been famously cagey about his personal life. As the New Yorker put it, “Sondheim has never wrestled explicitly with his sexuality or his upbringing. He avoided writing openly gay characters for most of his career.” He specializes instead in metaphor and symbolism: his stab at romantic memoir is “Company,” not “Angels in America,” and his meditation on life as a tortured, solitary artist is “Sunday in the Park with George,” not “Rent.”

The parallels between “Into the Woods” and the wreckage of the gay community seem heartbreakingly clear; in some ways, the wreckage is even starker than in the explicitly AIDS-focused “Rent,” Jonathan Larsen’s 1994 rock opera about bohemians living with HIV in the East Village. “Wake up,” snaps the Witch during Act Two of “Into the Woods.” “People are dying all around us.” Mothers lose children; children lose mothers. No romantic relationship remains intact. Those characters left alive at the end of the show are stunned, disbelieving, even traumatized by survivors’ guilt, since they are no more deserving of life than those who are gone.

For all the in-your-faceness of “Rent”—later mocked with spite but also some accuracy in Team America World Police in the faux Broadway number “Everyone Has AIDS!”—“Into the Woods” is more honest about the devastating effects of the epidemic. Larson lets only one character die, allowing the rest of the ensemble their happily-ever-after. Sondheim’s characters from “Into the Woods,” by contrast, are shell-shocked by the end of Act Two and, instead of pursuing their pleasures separately, come together, out to form what would later be called an intentional or “chosen family.”

You would be forgiven, however, for not seeing these parallels in the Disney version. Although the film is satisfying as a comedy, it falls apart as a tragedy, rushing through certain deaths and betrayals and negating others entirely. The Witch’s line, “People are dying all around us,” has been cut. A famous adultery sequence is reduced to a make-out session. In consequence, even during the show’s most moving song, “No One Is Alone,” there wasn’t a wet eye in the house.

America in 2014 is a different place in regards to the AIDS crisis than it was in 1987. HIV is no longer a death sentence, at least not for those privileged and affluent enough to have access to drugs; it is now considered a chronic disease. Nor is the subject taboo. If directors want to stage a show directly about the epidemic, they can revive “The Normal Heart” (as HBO did this year) or commission something new. Perhaps Disney felt that it was no longer necessary to approach the subject obliquely. Or perhaps Disney went saccharine in its attempt to satisfy, rather than challenge, as broad an audience as possible.

Either way, the original “Into the Woods” captured the terror of that cultural moment—where people were indeed dying all around us—as well as any piece of pop culture. In bowdlerizing it, Disney cuts the show off from its history, and us from our own.

Ester Bloom is an editor of The Billfold whose work appears in Slate, Salon, Creative Non-Fiction magazine, New York Magazine’s Vulture blog, Flavorwire, and the Toast, among numerous other publications. Follow her @shorterstory.

It’s worth remembering that Reagan went out of his way to kill as many homosexuals as possible by providing no funding for research, then lying that he did.

Disney has been turning horror shows into pablum since the 1920s. Mary Poppins wasn’t meant to be Julie Andrews either.

Thank you for this wonderful article. It’s important that modern-day audiences remember the historical context of this brilliant musical. I discovered ‘Into the Wood’ months after being diagnosed with HIV and it certainly resonated with me at the time- more so than other texts that are explicitly about HIV or the AIDS crisis. Anyone that has suffered the loss of a loved one, or a personal setback, or suffered seemingly insurmountable consequences in this world will find tremendous value in this musical. We’ve all been lost in the woods at some point in our lives. Just remember, no one is alone.

I haven’t yet seen the Disney movie version as I’m too hesitant that it will dilute the raw power and personal significance of the original. I encourage everyone to seek out the original Broadway production, which is available on DVD as a wonderfully filmed live performance.

“So we wait in the dark, until someone sets us free, and we’re brought into the light, and we’re back at the start. And I know things now, many valuable things, that I hadn’t known before. Do not put your faith In a cape and a hood. They will not protect you the way that they should. And take extra care with strangers, even flowers have their dangers. And though scary is exciting, nice is different than good.” -“I know Things Now,” Into the Woods

“No more giants waging war. Can’t we just pursue out lives with our children and our wives? But 'til that happy day arrives, how do you ignore- all the witches, all the curses,all the wolves, all the lies,the false hopes, the goodbyes, the reverses, all the wondering if what’s even worse is still in store? All the children. All the giants. Just no more.” -“No More,” Into the Woods (cut from the movie)

First, thanks for the article.

Yes, America is in a much different place than it was in 1987 but taboos have simply been shuffled about on the game board to minimize the past’s centuries-old, religion-induced prejudice and just as ancient fears of disease and death.

Though Disney recognized the economic potential of the gay market and moderated Walt’s lingering fascism fairly early and while this film might more reflect Disney’s current inability to craft a good movie than any censorship of past sexual prejudice, today’s corporate state across the board and large chunks of the population have a vested interest in keeping their dark involvements in an ugly past from the happy, peppy minds of their gung-ho, young gay employees and fellow citizens and gay offspring.

The right’s relative silence since the marriage tide turned more reflects the hugeness of their own closet-inhabiting membership, a shared element not not present with these other groups and thus incapable of partially moderating their hatred of black people, foreigners and women.

Nothing personal, dontcha know. It would have been political suicide if Reagan had responded to HIV as Gerald Ford did to the outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease in 1976.

Just a matter of NOKD. Not our kind, dear.

LD