The backlash is already here.

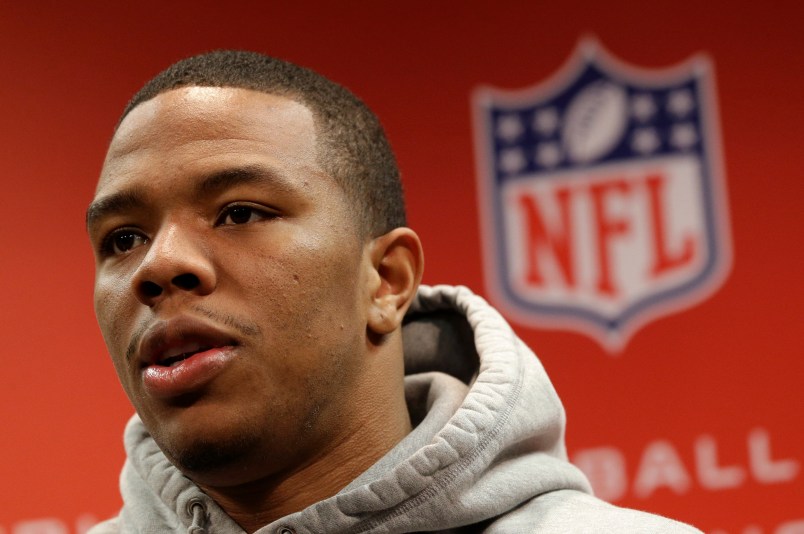

As an academic who studies domestic violence, I was surprised by the Ray Rice episode. Not because of the gruesome nature of the video allegedly depicting the former Baltimore Ravens star punching his then-fiancee out cold—24 percent of women will experience “severe physical violence” from an intimate partner sometime in their lifetime. I was surprised because it provoked universal condemnation.

Clear video evidence of domestic violence is very, very rare. People saw what happened and responded with unconditional outrage. At least most people. For now.

Once that the abuser has been thoroughly and publicly denounced, the pendulum inevitably swung back, with both cable news commentators and fans rushing to his defense.

Still, few have come to Ray Rice’s defense. His actions are indefensible. Instead, the backlash has been directed at those who call for stiffer penalties and resignations. As we saw Stephen Smith vilify the National Organization for Women and Fox News guests called those who object the so-called “anti-testicular police.” In sociology, we’ve got a name for this tactic; we call it “condemning the condemners.”

Nestled quietly in these counter attacks is the “man-hater” stereotype.

Rush Limbaugh may have popularized the term “feminazi,” but the man-hater trope has been around much longer than he has. Today, whether a woman publicly fights for equal-pay or for reproductive rights, she can soon expect armchair psychoanalysts to speculate about her true motivations.

Their diagnoses typically go something like this: “She’s just mad because men don’t find her attractive”; or “she’s just angry because some guy mistreated her.” Either way, her political appeals will likely be framed as emotional vendettas.

But what about the women accused of being man haters? How do they respond to these accusations? What do they really say about men?

Well, as expected, they talk about men quite a bit. However, what they say about men may come as a surprise. You see, women’s organizations know all too well that many presume that they are anti-men, and they’ve fashioned an unexpected public relations strategy to push back. Instead of spending their time complaining about men, they strategize ways to praise the men who “get it right.”

How do I know this? Because I have received that praise. Did I earn it? Well, sort of.

For a year and a half, I conducted ethnographic research in a setting that few men enter: an agency that assists victims of domestic violence and sexual assault.

During my time conducting this research, I was both a helper and an observer. I talked with some clients who feared for their life and others who just needed to talk. I filed paperwork and I showed clients where to go in court. I fetched take-out lunch orders and moved furniture with my pick-up truck. I did what most volunteers do. But, in the end, I got more applause and recognition than women who had been doing the same work for years.

The difference? I was a man in a setting that most men avoid.

This is the bizarre consequence of the man-hater stereotype: it creates an incentive for women’s organizations to refurbish their reputation by finding ways to celebrate men. In this strange turn of events, members of the same group (men) who created the mess (violence against women) also receive the loudest applause for offering to help clean it up.

This isn’t limited to the organization I worked with. Across the country, there are over 2,000 of these kinds of agencies — often known as “rape crisis centers” or “battered women’s shelters” — that know a lot about the man-hater stereotype. They fight it everyday.

They fight it not for themselves, but for the women who seek their services. They fear that if cops, lawyers, judges — or even victims themselves — see staff members as mere man haters, they won’t believe their claims about their clients.

Victim advocates and counselors know that the opinions of judges and police officers matter. Whispers of “man hater” in a courtroom hallway can tarnish their trustworthiness; and if they can’t vouch for their clients, they can’t help them. This can mean the difference between getting a restraining order signed for their client or leaving court empty handed. Thus, pushing back against the man-hater stereotype is an (indirect) way to help victims.

So how do they prove they aren’t man haters?

Here’s an example: After the end of my training on how to answer the crisis hotline and process walk-in clients, I was pulled aside by an elderly woman who was a regular donor to the organization. She profusely thanked me for “being interested.” None of the other women in my volunteer class (I was the only man) got the same extra praise. At the time, I thought it a little strange. But after I watched the same thing happen time and time again to other men affiliated with the organization, I came to see a pattern.

My presence inside these agencies offered something potentially even more valuable than the quality of services I delivered: As a man, I became a public relations tool. And what made my presence so valuable? Strangely enough, the man-hater stereotype.

I wasn’t the only guy to receive this kind of special treatment. During that year and a half I spent with the organization, I saw that granting men extra credit took a variety of forms. They featured stories of male volunteers in their fundraising letters. They boasted about how many men sought their services. They publicized the activities of any “men against domestic violence” organization in a 50-mile radius.

In other words, staff at these agencies try to prove they aren’t feminazis by recruiting men to work with them and patting them on the back when they show the least bit of effort.

This means that men who take a stand against abuse get disproportionate amounts of accolades for offering the smallest gestures of support. For men, just “being interested” earns extra praise. Meanwhile, the work of women who do just as much — if not more — goes largely unnoticed.

The idea that men can essentially benefit from the man-hater stereotype is a cruel irony. On average, women earn less than men at work (about 77 percent), hold less positions in congress (roughly 20 percent), and constitute only a scant amount of Fortune 500 CEO’s (4.8 percent). However, when it comes to domestic violence, women comprise 80 percent of all victims. In their lifetimes, one in five women will experience rape compared to one in seventy-one men.

Empirically, these statistics can make anyone furious. And for complaining about this state of affairs, what do women get? They get called man haters. And if men repeat these same statistics? They get a special feature in the next agency newsletter. In the end, it’s a win-win — for men.

So the next time someone condemns the condemners of domestic violence by insinuating that they are a bunch of vengeful man haters, remember this: The women who staff battered women’s shelters and rape crisis centers don’t hate men, they desperately need men. They are actively searching for more ways to get men involved. What they hate is abuse, no matter who does it.

Kenneth Kolb is an associate professor of sociology at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. He is the author of Moral Wages: The Emotional Dilemmas of Victim Advocacy and Counseling, University of California Press (2014).

“What they hate is abuse, no matter who does it.” Perhaps this is the way it should be presented. People against violence, violence against someone else, violence against children, wives, husbands and pets (this type of violence seems to hit a higher outrage scale than that against wives/women).

It isn’t that women want to be singled out as victims, they want to be treated as humans. Because our culture/media/activities are depicted from a strong male point of view and always have been, it isn’t any wonder that the men feel threatened and uncertain. If you have been told and presented in one way for most of history it isn’t any wonder they feel like the rug is being pulled out from under them and by those “others” who have been and are depicted as weaker, less intelligent, subservient sex objects. Even with all of the dialog and open discussion of the issues, still our commercials and advertising of women is mostly sexual in nature.

Be that as it may, it still that women and many men as well are against violence of any kind against another human/creature. I doubt you will find men who are against domestic violence but find it OK to torture animals and the same with women. This isn’t a us against just domestic violence it is us against violence period.

Just like pro-choice isn’t about being pro-abortion, women against domestic violence and rape are not pro-violence against men.

What might help is if we could move people like Fox news pundits that have become prostitutes Mr. Ailes and his anti-women and children and freedom messages. We need to move people like Rush Limbaugh out of the spotlight. We need to move him to the dark and not highlight every gum ball that comes from his mouth. The same with all of the extreme right wing anti-humane pundits. Right now they are at the top of every blog, news outlet, and journalists “go to” articles and topics. What would happen if we highlighted more rational analysis and analysts.

It’s all about perspectives and right now we only see the commercial negative perspectives, and we only have ourselves to blame because we click on, pass on, and buy this violence in our lives.

Hi Folks,

My name is Ken and I am the author of this piece. I’ve been a TPM Prime member from the very beginning.

I’m happy to answer any questions about the piece, or my research in general.

Thank you Ken for this piece.

Thank you also for articulating the kind of experience which resonates with me because of the echoes it evokes of my own experience, beginning as a volunteer at a women’s shelter/rape crisis center 24 years ago, and evolving into a career both in agencies, and now in private practice, trying to help people on both sides of the issue deal with the tragic reality and consequences of interpersonal violence in their own lives.

It is understandable that members of society who are socialized to include power and control, and aggression, in their toolkit of acceptable responses to perceived danger, kind of automatically assume that if someone opposes their chosen methodology of responding to perceived danger then that response is going to involve power and control, and aggression, being aimed at them.

But I like to think that the more enlightened advocates of non-violence, equality, and respect for others, understand that power and control and aggression are unacceptable choices for us also, if only because they are fundamentally counter-productive.

It has been that issue of counter-productivity which has served me well as a key in helping me to understand that the best response to intimate violence is not retribution or revenge, but helping aggressors alter their behavior so as to make the future better than the past.

Several experiences have contributed to reinforce that approach. I came to understand that most thoughtful victims are not seeking revenge or retribution as their primary goal, post-victimization, but are seeking a sense of safety in their future, a safety which is not ensured by retribution, revenge, or punishment, but only is realizable when their aggressor understands the full dimensions of their abusive behavior, understands how counterproductive it was when measured against the underlying intent of their actions, and thus come to regret their actions for the harm it has caused to both their victim and themselves, then, finally resolve to make the future better than the past.

As I came also to understand that every aggressor I have ever worked with, sincerely, and, on a superficial level at least, understandably, considered themselves to be not just a victim but the victim, I began to look a little more closely at their experience.

I came to understand that their historical experience as victims has meshed with their expectations of how society would respond to their behavior and thus blinded them to opportunities for positive change, as they steeled themselves against the hostility and danger that they had learned was the usual response to any of their actions, and instinctively reached into their toolkit of aggression as they sought to protect themselves against their perceived danger.

Ironically, that helped me come to understand that the opportunity for positive intervention came through helping aggressors feel safe with me and see me as someone who respected their fundamental humanity enough to want to help them make their lives better.

That has helped enormously to make it possible for many, though admittedly not all, to listen to me when I speak truth to them, help them gain a clearer perspective on both their intent and the counter-productivity of their action, then find ways of responding to the future better than they have the past.

It has no doubt helped me to become more effective because this has not just been an academic exercise for me but a journey which I have personally shared with all of my clients, largely because it has mirrored my own struggles with my past and present feelings, thoughts, and behaviors.

Ultimately though, it has been a rewarding experience for me, and I have reason to believe it’s been beneficial for a few others also.

Thank you, David, for your thoughtful comments.

Your dedication to the cause is admirable.

Ken

CLK,

I agree with your suggestion that agencies that assist victims should continue to oppose all forms of violence. I think that is the direction they are currently heading. As more men each year admit to being victims of sexual violence (most often, from other men) there will be a greater need for services to help them.