The critics of President Obama’s actions on Cuba are trying to fit a decades-old problem into a post-9/11 “Axis of Evil” mindset. But while conservatives are condemning Obama for “coddling dictators” (just as they once attacked him for “palling around with terrorists”), their attack requires forgetting a huge amount of history. Here is what you need to know—and what they have forgotten.

Many Americans have thought of Cuba as an enemy for more than half a century. Today’s critics of President Obama argue as if tensions began during the Cold War, when in 1960 Fidel Castro’s Cuba partnered with the Soviet Union, and have simmered ever since, almost bringing the world to war in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

A deeper view of history offers a very different picture. For more than 150 years, both American and Cuban leaders have dreamed of tying the nations together.

In the late 1840s, Cuban slaveowner Narciso López led a series of revolts in an effort to gain independence from Spain, preserve slavery on the island, and ally with the United States—specifically, with the slave South. López’s efforts failed and he was executed in 1851, but a few years later, Franklin Pierce’s pro-slavery Minister to Spain, Pierre Soulé, pursued a similar plan on behalf of the United States. Soulé and others drafted the secret Ostend Manifesto (1854), which argued for a U.S. purchase or annexation of the island and, when made public, led to a diplomatic crisis that almost erupted in war.

When military conflict came, in the Spanish American War of the late 1890s, the United States and Cuban revolutionaries allied in opposition to Spanish rule. This time, the Cuban leader was far more radical than López: José Martí, a poet, journalist, professor, and revolutionary who had spent decades as an exile in New York City and whose writings and efforts contributed greatly to the resistance against Spain. Martí’s death at the Battle of Dos Ríos in 1895 produced a surge of Cuban and American sympathy for the revolution, and thus in both life and death Martí played a prominent role in bringing the United States into the Spanish American War and into a relationship with Cuba that would last for half a century after the war’s end.

Over the course of those decades, from 1895 until 1959, the United States participated both openly and covertly in Cuba’s political evolution, helping install and remove numerous leaders. Fulgencio Batista was at the center of those histories, from the time he led a 1933 military revolt that overthrew Cuba’s president through his own 1940 election to the presidency and finally a 1952 coup that returned him to power. In his earlier days Batista was more like Martí, a revolutionary dedicated to social reform and the people. But by the 1950s, he had evolved into a strident anti-Communist with deep ties to U.S. corporate interests on the island. So when Fidel Castro and his fellow Communist rebels led the 1959 revolution that overthrew Batista, the U.S. severed its longstanding ties to Cuba.

Here is what Obama’s critics are missing: the fact that Cuban-American connections have evolved, shifted, and most of all, endured, across nearly two centuries. Pioneering Caribbean scholar Edouard Glissant described the Americas as created through a process of “creolization,” of interdependent relationships and influences across many nations. In announcing his decision, President Obama put it more simply, quoting none other than José Martí: “Todos somos Americanos.” Indeed we are, and if we start there, we can realize that 1960 to 2014 need not define the future of the U.S.-Cuba relationship. Indeed, it doesn’t even define the past.

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English Studies at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

Of course they’re tunnel-visioned about the Cold War communist era: they’ve been trying to recapture that mindset and spread it from coast to coast ever since Saint Reagan single-handedly saved the universe from communism and brought down the USSR by making a speech in Germany. A populace afflicted with that mentality favors conservative policies and ideology greatly and they’ve been in a desperate search for a replacement bogeyman ever since.

Much like with religion, Conservatives pick and choose the parts they like, and pretend the rest is bullshit or never happened.

My sense is, the Cubans of FL have been a powerful and regular ally of the GOP (and some Democrats) for many years. This alliance has kept the embargo in place, but its foundation has been electoral politics. No Cuba in exchange for your financial and electoral support.

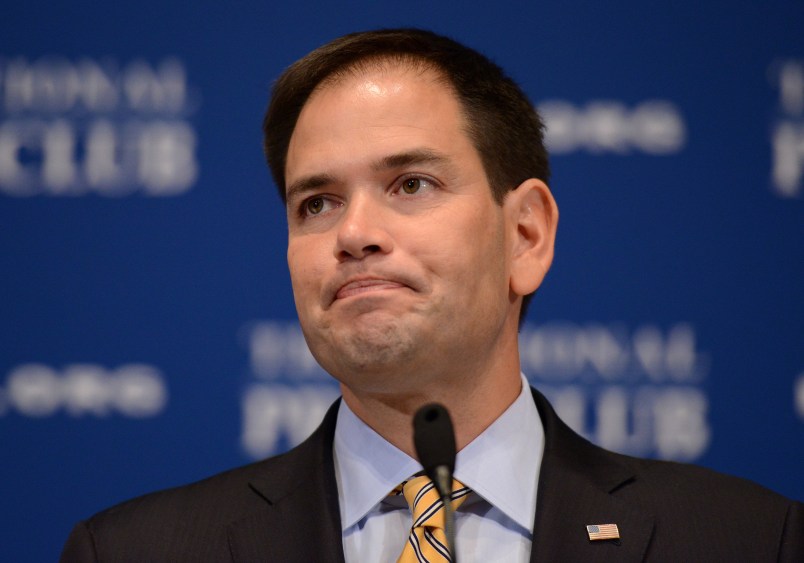

So Rubio (and Menendez, perhaps) is going back to the same well and hoping for the same electoral magic. But I think the electorate has moved on, and the old black magic won’t work anymore.

Some of it has, but some of it hasn’t. The question is whether the supporters of this move or the opponents will be more motivated to vote as a result. Even if 60% of the Cuban-American community supports it, if most of that 60% don’t vote for the Democrat, it won’t matter.

I loved Rubio comparing Obama’s negotiating skills to Carter’s, as if it was an insult.

I sincerely doubt Rubio (or any of the other current crop of moronic Republicans) will ever be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize.