This week, local and national media have been stunned by the revelation that Missouri state Rep. Rick Brattin (R-Harrisonville) filed H.B. 131, a bill that would change the state’s informed consent requirements for an abortion to mandate that the pregnant person obtain written consent from the “father of the unborn child.” The only thing surprising about Missouri’s proposed “father’s consent” abortion bill? That it took so long for it to get filed.

“Spousal consent” as a concept has always been floating around the periphery of the abortion debate, usually in op-eds bemoaning the man’s lack of say in a woman’s decision to terminate, or in false-equivalency arguments that if a man can’t determine whether or not a woman carries his child to term, then she shouldn’t have the right to demand child support if she does decide to give birth. As an abortion restriction, however, many people wrongly consider it a settled issue, citing the 1992 Supreme Court ruling of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, in which spousal notification was one of the many new restrictions proposed by the state of Pennsylvania. Spousal notification was the only restriction in the bill that the justices felt placed an undue burden on the right to an abortion (the others were a 24-hour wait and parental consent), setting the new standard that restrictions should be allowed as long as they didn’t infringe too far on a person’s right to terminate a pregnancy.

Only three justices from that court are still on today’s Supreme Court bench, and of those three, two of them ruled against the majority opinion. The third? Justice Anthony Kennedy, often considered the swing vote in every abortion litigation that court has seen since, and the vote that many believe could eventually overturn Roe v. Wade.

With abortion opponents eagerly looking for just the right test case to bring to the highest court in order to potentially overturn Roe in the near future, it’s hard to image anyone interested in promoting a bill that could endanger that goal. Perhaps for that reason alone, spousal consent bills since 1992 have been largely non-existent.

Of all the states in the country, only Ohio has introduced similar legislation with a “father’s consent” bill in 2007 and 2009. Neither managed to pass in the state legislature. While proposed bills disappeared thereafter, the issue itself has always been on the backburner.

National Pro-Life Association, an anti-abortion group best known for its support of a federal Life at Conception Act (a bill that would grant “personhood” to a fertilized egg and end abortion and potentially many forms of contraception), has been surveying candidates for years to find out if they would support spousal consent if they were elected. NPLA is best known currently for their unswerving support of Kentucky Senator Rand Paul, who is believed to be considering a 2016 Republican presidential run.

If a bill to mandate consent of the man who impregnated the woman was going to pop up anywhere, it makes sense that Missouri did it first. The state is now down to just one clinic providing abortions, and in recent sessions has passed a mandatory 72-hour wait, mandatory ultrasounds, even more expansive “conscience” objections to abortion and birth control and a ban on later abortions. Even with all of these restrictions in place, the state still has multiple bills on tap for next session.

Missouri also has had a model consent bill floating around the state legislature since at least early 2013, although no one was willing to sign on as a sponsor before now. In February of 2013, Missouri state Rep. Keith English, a Democrat, told me that there was a “spousal consent” bill, but that he chose not to sign on as the primary sponsor because it had too many “loopholes.”

“You and I can both sit here and say that if there was some law that said that the father gets a choice that any woman could bring any man to sign in and say he was the father,” Rep. English told me in an interview back in 2013. “What do you want to put in there? That there is going to have to be some sort of DNA test done before she can have an abortion? There are so many loopholes in that idea and so many financial constraints on both sides.”

“Loopholes” don’t appear to be completely closed in Rep. Brattin’s bill, either. As he told Molly Redden at Mother Jones, those who claim to have been impregnated by rape will have to prove it was a “legitimate” rape by having a police report to back it up, and the doctor will require a written, notarized affidavit if the pregnant person claims the man who impregnated her is now deceased. That doesn’t address Rep. English’s previous concern that she could pass any person off as the fetus or embryo’s father, however, leaving that avenue wide open.

Ohio did in fact try to address issues of masquerading fake fathers and the “what if I don’t know the father?” arguments during their own bill debate. Their solution? A list of potential men who may have impregnated a person, and paternity tests all around. Should a man be caught trying to pass himself off as the father in order to help a pregnant person get an abortion, he would be charged with “abortion fraud,” as would anyone who assisted in the deception.

Is consent from the person who impregnates someone ever going to be law? Hopefully not. If it was going to be, however, Missouri is probably the likeliest to pass it. The state currently has an anti-abortion majority so large it can override any veto that Democratic Governor Jay Nixon offers. Meanwhile, its anti-abortion activist community is so powerful that even self-proclaimed pro-life Republicans are complaining that the “constant purity exams” they are being forced to undergo are almost impossible to maintain.

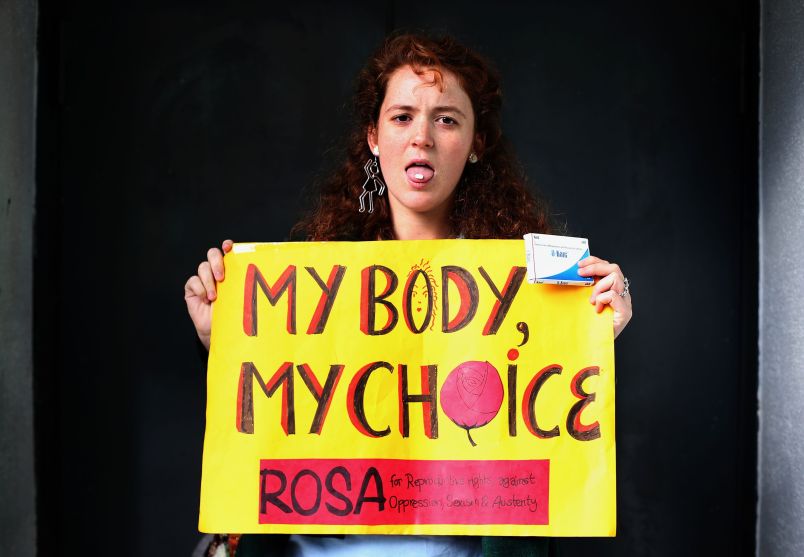

Even if it never makes it into law, or gets blocked by the courts if it does, H.B. 131 will inevitably serve its real purpose— which is to reinforce the idea that women cannot be entrusted with ownership over their own bodies. Requiring consent from a male partner legally infantilizes the woman, marking her as not mentally and emotionally mature enough to decide to terminate a pregnancy on her own. Just as parental consent is a means of telling a teen that she is too immature to know what is in her own best interest if she wants an abortion (but not, of course, if she wants to remain pregnant and give birth), spousal or partner consent gives a man that same authority over the person who is pregnant, with the implied belief that he—not she—should get final say in whether she carries a pregnancy to term.

Rep. Brattin’s bill is about more than just consent. It is about demoting women to a subservient role that comes under the authority of a man, just as a minor is the “property” of her parents and cannot act without their permission, either. Should H.B. 131 pass either chamber, much less both, the state of Missouri will have made it clear exactly how they view the women in the state—immature, indecisive, and needing the guidance of a man to make their pregnancy decisions for them.

Robin Marty is a freelance writer, speaker and activist. Her current project, Clinic Stories, focuses on telling the history of legal abortion one clinic at a time. Robin’s articles have appeared at Cosmopolitan.com, Slate, Rolling Stone, Bitch Magazine, Ms. Magazine and other publications.

(((Speechless)))

when a man ‘gives it’ to a woman, i believe she can do whatever she wants with ‘it’. there has clearly been a transfer of ownership.

Read Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” where women are forced to bear children and have no choice in the matter. No longer in the realm of science fiction…

DID you GET Your HUSBand OR a MALE relaTIVE to APPROVE thIS EXtreMELY oFFEnsIVE anti-AMericaN cOMMENt. LIBtard CULTure of DEATH!!1!!!one!!11!!11!!!

Might as well make women slaves as in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia to name a couple. The south is great!!!