Federal prosecutors are prepared to enter into a plea deal with President Biden’s son Hunter, according to a document released on Tuesday.

Continue reading “Hunter Biden Reaches Plea Deal On Three Federal Charges”Cannon Signals Trump To Get Speedy Trial, For Now

U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon for the Southern District of Florida set a preliminary trial date in the Trump Mar-a-Lago case for Aug. 14 in a Tuesday morning order.

Continue reading “Cannon Signals Trump To Get Speedy Trial, For Now”Don’t Lose Your Bearings In The Debate Over DOJ’s Initial Slowness In Investigating Trump

A lot of things happened. Here are some of the things. This is TPM’s Morning Memo.

DOJ Needed A Different Playbook

The big WaPo story over the weekend about the early delays in investigating the higher-ups in the conspiracy to overturn the 2020 election has set off a new round of invective and backbiting in a public debate that I ultimately find a bit dispiriting and unenlightening.

I’ll put my cards on the table so you know where I’m coming from: I do think DOJ was slow off the mark in 2021 in investigating the Jan. 6 attack as the culmination of a wide-ranging conspiracy that we date back to beginning in April 2020.

I generally don’t think the slowness was the result of malfeasance, some underground FBI effort to protect Trump, or malpractice. Rather, it was due to the same lack of imagination and understanding about the threat to the Republic that Trump and MAGA world pose that has bedeviled our politics for coming up on a decade.

I’m not going to rehash the whole debate here. But I will suggest that the arguments that don’t take into account the ticking of the clock toward the next election and the narrow window that left DOJ in which to achieve justice are not fulling grappling with the problem.

If the big criminal case against Trump had been, say, financial fraud, then the normal DOJ playbook of slow, careful, methodical working of its way from small fish up to bigger fish would have made sense. But the big case against Trump involved the threat to democracy itself, and specifically to elections. The next election, Trump’s potential and now actual candidacy, the risk that the 2020 conspiracy would continue in 2024, the real chance that Trump would use his re-election to entrench himself in power in extra-constitutional ways, those were the new, different, and unprecedented challenges that nearly everyone, including I’m afraid the highest levels of the Justice Department, have been slow to internalize.

As I’ve said before, DOJ seems fully on track now. The slowness is water under the bridge, though we’ll still be paying the price for that potentially for years to come. Onward though. It’s not worth losing ourselves in this debate.

Judge Sets Trial Date For MAL Case

A few moments ago, U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon issued a scheduling order in the Mar-a-Lago case, setting an initial trial date of Aug. 14, 2023.

First off, this is not going to trial in August of this year. Politico’s Kyle Cheney explains why.

But this still remains an important early marker. Had Cannon set the initial trial date for August 2024, for example, it would have signaled a slow-walking of the case that guaranteed it would not be complete before the election.

It’s still a very tight window, and she still will have many opportunities to slow-roll the case. But she’s not doing it here with the initial trial date.

Trump Keeps On Making Admissions

The last Morning Memo before this one was devoted to Trump’s ongoing public confessions of his Mar-a-Lago criming. He can’t stop. Won’t stop. In part one of a two-part interview, the second of which has yet to air, Trump told Fox News’ Bret Baier:

Here’s the video:

‘Even Stronger Than I Expected’

Ruth Marcus: A former prosecutor explains what surprised her most about Trump’s indictment

Someone Finally Asked THE Question

Trump Attorney Cites ‘Irreconcilable Differences’

Trump attorney James Trusty, who withdrew from his representation of Trump in the Mar-a-Lago case immediately after the indictment was handed down, has also stepped aside from Trump’s civil defamation lawsuit against CNN. Trusty cited “irreconcilable differences” with Trump as the basis for withdrawal.

What Does This Mean Exactly?

Former Vice President Mike Pence is joining with the Donald Trump and the MAGA wing of the GOP in promising to bring the Justice Department to heel. But he seems to be suggesting he would do what every president does: Select political appointees of his own choosing for DOJ.

You Thought Trump I Was Bad …

Wait for Trump II:

Mr. Trump has been selling his name to global real estate developers for more than a decade. But the Oman deal has taken his financial stake in one of the world’s most strategically important and volatile regions to a new level, underscoring how his business and his politics intersect as he runs for president again amid intensifying legal and ethical troubles.

Oh …

The Fox News producer behind the Biden is a “wannabe dictator” chyron is no longer with the network:

Almost Funny Or Actually Funny?

The RNC is waking up to the fact that being against early voting and voting by mail is electoral suicide. But its change of heart is making the My Pillow guy go apeshit, TPM’s Hunter Walker reports.

Must Read

I’m a little biased but TPM’s Kate Riga has the best explanation I’ve seen to date on how and why the risk of a government shutdown has grown in the days since a debt ceiling deal was finalized.

The mechanisms that the debt ceiling deal put in place to avert a government shutdown are more complicated than they first appeared from the news coverage. Kate digs in to what the debt ceiling deal provided and how the various stakeholders are interpreting and responding to them.

It’s worth a read to get yourself grounded in the underlying dynamics.

‘I Just Need A Camera For Streaming’

The FBI has arrested a Michigan man for allegedly planning a mass shooting at a synagogue in East Lansing.

The Dobbs Anniversary

WaPo: How Democrats will highlight abortion restrictions this week

Think Big

Smithsonian: “Scientists have detected the presence of the sixth and final essential ingredient of life in ice grains spewed into space from the ocean of Saturn’s moon Enceladus.”

Like Morning Memo? Let us know!

Why the 9/11 Families Are So Angry With the PGA Tour

This story first appeared at ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

When the PGA Tour announced a long-term partnership with LIV Golf, the upstart organization bankrolled by Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, no one sounded angrier than survivors of the 9/11 attacks and the families of those who were killed.

The pact on June 6 marked an abrupt reversal for the PGA, which had fought LIV Golf since it emerged in 2021. The rival league courted star golfers with vast payouts that were widely seen as part of a global public-relations campaign by the Saudi government.

“All of these PGA players and PGA executives who were talking tough about Saudi Arabia have done a complete 180,” one spokesperson for the families, Brett Eagleson, said in an interview. “All of a sudden they’re business partners? It’s unconscionable.”

Before the new alliance, PGA officials had highlighted the Saudi government’s alleged role in the 9/11 attacks, along with the kingdom’s record of human rights abuses, as important reasons for their opposition to LIV Golf.

The Saudi government has long denied that it provided any support for the attacks. But, over the past few years, evidence has emerged that Saudi officials may have had more significant dealings with some of the plotters than U.S. investigations had previously shown.

Since 2017, the 9/11 families and some insurance companies have been suing the Saudi government in a Manhattan federal court, claiming that Saudi officials helped some of those involved in the Qaida plot.

The Saudi royal family was a declared enemy of al-Qaida. In the early 1990s, it expelled Osama bin Laden, the son of a construction magnate, and stripped him of his citizenship. At the same time, the kingdom funded an ambitious effort to propagate its radical Wahhabi brand of Islam around the world and tolerated a religious bureaucracy that was layered with clerics sympathetic to al-Qaida and other militant Islamists.

From the start of the FBI’s investigation into a possible support network for the 9/11 plot, one of its primary suspects was a supposed Saudi graduate student who helped settle the first two hijackers to arrive in the United States after they flew into Los Angeles in January 2000.

The middle-aged student, Omar al-Bayoumi, told U.S. investigators that he met the operatives by chance at a halal cafe near the Saudi Consulate in Culver City, California. The two men, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, were trained as terrorists but spoke virtually no English and were poorly prepared to operate on their own in Southern California.

Bayoumi insisted he was just being hospitable when he found Hazmi and Mihdhar an apartment in San Diego, set them up with a bank account and introduced them to a coterie of Muslim men who helped them for months with other tasks — from buying a car and taking English classes to their repeated but unsuccessful attempts to learn to fly.

As ProPublica and The New York Times Magazine detailed in an in-depth report on the FBI’s secret investigation of the Saudi connection in 2020, agents on the case suspected that Bayoumi might be a spy. He seemed to spend most of his time hanging around San Diego mosques, donating money to various causes and obtrusively filming worshippers with a video camera.

Yet both the FBI and the bipartisan 9/11 Commission accepted Bayoumi’s account almost at face value. In a carefully worded joint report in 2005, the CIA and FBI asserted that they had found no information to indicate that Bayoumi was a knowing accomplice of the hijackers or that he was a Saudi government “intelligence officer.”

But FBI documents that were just made public last year sharply revised that assessment.

While living in San Diego, one FBI document concludes, Bayoumi was paid a regular stipend as a “cooptee,” or part-time agent, of the General Intelligence Presidency, the Saudi intelligence service. The report adds that his information was forwarded to the powerful Saudi ambassador in Washington, D.C., Prince Bandar bin Sultan, a close friend to both presidents Bush and their family. The Saudi Embassy in Washington did not immediately respond to questions about Bandar’s alleged relationship with Bayoumi.

As Bayoumi was helping the hijackers, FBI documents show, he was also in close contact with members of a Saudi religious network that operated across the United States. He also dealt extensively with Anwar al-Awlaki, a Yemeni American cleric who the documents suggest was more closely involved with the hijackers than was previously known. Awlaki later became a leader of al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula and was killed in a 2011 drone strike ordered by President Barack Obama.

One of the Saudi officials with whom Bayoumi appeared to work, Musaed al-Jarrah, was both a key figure in the Saudi religious apparatus in Washington and a senior intelligence officer. After being expelled from the United States, Jarrah returned to Riyadh and worked for years as an aide to Prince Bandar on the Saudi national security council.

Another Saudi cleric with whom Bayoumi worked, Fahad al-Thumairy, was posted to Los Angeles as both a diplomat at the Saudi Consulate and a senior imam at the nearby King Fahad Mosque — a pillar of the global effort to spread Wahhabi Islam that had opened in mid-1998.

According to another newly declassified FBI document from 2017, an unnamed source told investigators that Thumairy received a phone call shortly before the two hijackers arrived in Los Angeles from “an individual in Malaysia” who wanted to alert him to the imminent arrival of “two brothers … who needed their assistance.”

In mid-December 1999, according to the 9/11 Commission report, a key Saudi operative in the plot, Walid bin Attash, flew to Malaysia to meet with Hazmi and Mihdhar. Although the men were kept under surveillance by Malaysian security agents, they were allowed to fly on to Bangkok and then Los Angeles, using Saudi passports with their real names. The FBI source said that Thumairy arranged for Mihdhar and Hazmi to be picked up at the Los Angeles International Airport and brought to the King Fahad Mosque, where they met with him. Thumairy and Jarrah have both denied helping the hijackers.

The FBI revelations were especially stinging for the 9/11 families because previous administrations made extraordinary efforts to keep them under wraps. President Donald Trump, who promised to help the families gain access to FBI and CIA documents, instead fought to shield them as state secrets. (Trump has been a vocal supporter of LIV Golf, hosting several of its tournaments at his golf courses and saying after the merger, “The Saudis have been fantastic for golf.”)

The more recent disclosures — which came in documents declassified under an executive order that President Joe Biden issued just before the 20th anniversary of the attacks — are now at the center of the federal litigation in New York. While the families are pressing to reopen discovery in the case based on the new FBI information about Bayoumi and others, lawyers for the Saudi government continue to insist there is no evidence of the kingdom’s involvement in the plot.

To prove their case, the families must show that people working for the Saudi government either aided people they knew were planning a terrorist action in the United States or helped members of a designated terrorist organization like al-Qaida. At the time that Bayoumi aided Hazmi and Mihdhar in California, officials have said, the CIA and Saudi intelligence had identified the two as Qaida operatives.

The two federal judges overseeing the Manhattan litigation have yet to rule on requests from the families, based on the newly declassified FBI documents, for further inquiries to the Saudi intelligence service.

The PGA official who brokered the new alliance with LIV Golf, James J. Dunne III, told the Golf Channel he was confident that the Saudi officials with whom he negotiated were not involved in the 9/11 plot. Dunne, an investment banker, added, “And if someone can find someone that unequivocally was involved with it, I’ll kill him myself.”

Eagleson, whose father, John Bruce Eagleson, died in the same south tower of the World Trade Center where 66 employees of Dunne’s bank were killed, suggested that he read the declassified FBI documents about Bayoumi, Thumairy and other Saudis. “It’s the same government,” Eagleson said.

Wisconsin Republicans Sowed Distrust Over Elections. Now They May Push Out the State’s Top Election Official.

This article first appeared at ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Meagan Wolfe’s tenure as Wisconsin’s election administrator began without controversy.

Members of the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission chose her in 2018, and the state Senate unanimously confirmed her appointment. That was before Wisconsin became a hotbed of conspiracy theories that the 2020 election had been stolen from Donald Trump, before election officials across the country saw their lives upended by threats and half-truths.

Now Wolfe is eligible for a second term, but her reappointment is far from assured. Republican politicians who helped sow the seeds of doubt about Wisconsin election results could determine her fate and reset election dynamics in a state pivotal to the 2024 presidential race. Her travails show that although election denialism has been rejected in the courts and at the polls across the country, it has not completely faded away.

One of the six members of the election commission has already signaled he won’t back Wolfe. That member is Bob Spindell, one of 10 Republicans who in December 2020 met secretly in the Wisconsin Capitol to sign electoral count paperwork purporting to show Trump won the state, when that was not the case.

If retained by a majority of the commissioners, Wolfe would have to be confirmed by the state Senate. But the Wisconsin Legislature is dominated by Republicans who buttressed Trump’s false claims about fraud in the 2020 election. The Senate president has in the past called for Wolfe’s resignation after a dispute over how voting was carried out in nursing homes. Some other senators have registered their opposition to reappointing Wolfe, as well.

Republicans and Democrats have fought to a power stalemate in Wisconsin in recent months. Voters reelected a Democratic governor in November of last year and this year elected a new Supreme Court justice who tilts the court away from Republican control.

A December 2022 report by three election integrity groups looking at voter suppression efforts nationwide concluded that in Wisconsin the threat of election subversion had eased. “The governor, attorney general, and secretary of state, all of whom reject election denialism, were re-elected in the 2022 midterm election,” they wrote.

Still, the groups warned, Wisconsin continues to be a state to watch, noting “the legislature now has an election subversion-friendly Republican supermajority in the senate and a majority in the assembly.”

“We are in a better place,” attorney Rachel Homer of Protect Democracy said of the national landscape in a recent press conference following an update to that study. “That said, the threat hasn’t passed. It’s just evolved.”

There are fears that the state Senate could refuse to reappoint Wolfe and instead engineer the appointment of a staunch partisan or an election denier, tilting oversight of the state’s voting operations.

“It could be a huge disruption in our elections in Wisconsin,” said Senate Democratic leader Melissa Agard. “If you have someone who has this pulpit using it to spew disinformation and harmful rhetoric, that is terrible.”

As for Wolfe, she mostly only speaks out about election processes and stays out of the political fray.

Through a spokesperson, Wolfe declined to comment in response to ProPublica’s questions. In a public statement issued last week, she said she found it “deeply disappointing that a small minority of lawmakers continue to misrepresent my work, the work of the agency, and that of our local election officials, especially since we have spent the last few years thoughtfully providing facts to debunk inaccurate rumors.

“Lawmakers,” she continued, “should assess my performance on the facts, not on tired, false claims.” The commission created a page on its web site to address rampant misinformation.

Wolfe has maintained the support of many election officials throughout the state.

She has been “a great patriot” for not quitting despite the attacks and for being willing to be reappointed, said the executive director of the Milwaukee Election Commission, Claire Woodall-Vogg. “I think she understands the pressure and understands the peril that the state could face if she’s not in that position.”

A Honeymoon, Then Trouble

The state commission was created in 2016 by Republican state officials unhappy with the independent board of retired judges that then oversaw elections. They created a panel of three Democrats and three Republicans, advised by an administrator with no political ties.

The commission provides education, training and support for the state’s roughly 1,900 municipal and county clerks, who in recent years have faced cybersecurity threats, budget woes, shortages of poll workers and other challenges. The commission also handles complaints, ensures the integrity of statewide election results and maintains Wisconsin’s statewide voter registration database. The administrator manages the staff, advises commissioners and carries out their directives.

At first the newly established commission had someone else at the helm: Michael Haas, who had served the prior agency, the Government Accountability Board, which had investigated GOP Gov. Scott Walker for campaign finance violations. (The state Supreme Court halted the probe in 2015, finding no laws had been broken.) As a result, Haas did not win state Senate confirmation and stepped down.

The six commissioners then unanimously promoted Wolfe, the deputy administrator, to the top post in March 2018. She won unanimous confirmation in May 2019 in the Senate, which then-state Senate majority leader Scott Fitzgerald said looked to her to “restore stability.”

“I met with Ms. Wolfe last week and was impressed with her wide breadth of knowledge regarding elections issues,” Fitzgerald, now a U.S. representative, said at the time. “Her experience with security and technology issues, as well as her relationships with municipal clerks all over the state, will serve the commission well.”

The bliss did not last.

Wisconsin was one of the first states to put on an election following the start of the pandemic in 2020, amid lockdowns, fear and uncertainty. The primary that April was chaotic, with legal fights over whether to even hold the contest. Local officials closed some polling places. There were long lines in Milwaukee, Green Bay and elsewhere. The governor deployed the state National Guard to assist, and mail-in voting soared.

Later in the year, after it became clear that Trump had lost Wisconsin to Joe Biden in the election the previous November, state Republicans blasted the elections commission for accommodations made during the pandemic, such as the wider use of ballot drop boxes and unmonitored voting in nursing homes. Critics claimed the moves increased the likelihood of fraud and tainted the election.

U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wisconsin, proposed dissolving the commission and transferring its duties to the GOP-controlled Legislature. Talk of that ended with the reelection last year of Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. The Legislature would need his approval to disband the commission.

“What’s happened over the last six years, in particular since the Trump years, is there’s been a systematic attempt to undermine the work of the Wisconsin Elections Commission,” said Jay Heck, executive director of Common Cause in Wisconsin. “Because it’s apparently not as responsive in a partisan way to the Republicans as they would like.”

Wolfe became a target. Many Republicans accused her of facilitating the awarding of private pandemic-related grants to election clerks that those critics claimed fostered turnout in Democratic areas, though the money was widely distributed.

They also criticized Wolfe for allowing the commission to vote in June 2020 to send absentee ballots to nursing homes during the health emergency rather than have special poll workers visit to assist residents and guard against fraud. Republicans discovered that some mentally impaired people in the facilities who were ineligible to vote cast ballots in Nov. 2020, though the numbers were small and not enough to change the election results. Municipal clerks had received only 23 written complaints of alleged voter fraud of any type in the presidential election, the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Audit Bureau found.

Wolfe was the target of lawsuits and insults. Michael Gableman, a former state Supreme Court justice and Trump supporter tapped by the Assembly Speaker to lead a 2020 election investigation, mocked her attire: “Black dress, white pearls — I’ve seen the act, I’ve seen the show.”

One conservative grassroots group, H.O.T. Government, has been sending out email blasts urging Wolfe’s ouster, referring to her as the “Wolfe of State Street.”

Wolfe does have champions, but they are not as vocal as her critics. “I think she’s done an outstanding job with running the Wisconsin Elections Commission here,” said Cindi Gamb, deputy clerk-treasurer of the Village of Kohler. “She’s been very communicative with us clerks.”

Gamb is the first vice president of the Wisconsin Municipal Clerks Association, but she said the group’s rules bar it from making endorsements.

Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell finds the assaults on the once-obscure bureaucrat troubling. “What has Meagan done to deserve the abuse she’s gotten?” he said. “Nothing.”

Wolfe did receive the support of 50 election officials nationwide who called her “one of the most highly-skilled election administrators in the country” in a 2021 letter to the Wisconsin Assembly speaker. Wolfe is a past president of the National Association of State Election Directors.

And she has had the backing of a bipartisan business group that in February of last year sent a letter of appreciation to her and the commission. “Although the 2020 elections were among the most successful in American history thanks to your efforts, we recognize election administrators nationwide are facing increasing unwarranted threats and harassment. We hereby offer our sincere gratitude and full support,” said the letter from Wisconsin Business Leaders for Democracy.

The 22 signers included the president of the Milwaukee Bucks, the former CEO of Harley-Davidson and two top members of the Florsheim shoemaker family.

An Undecided Fate

Wolfe’s term expires July 1.

To avoid a showdown, some legal experts are exploring whether the commission could take no action and just allow Wolfe to continue past June 30, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. They’ve pointed to the example of Fred Prehn, a dentist appointed to the state Natural Resources Board who refused to leave after his term expired in May 2021, preserving GOP control over the board.

The state Supreme Court ruled last year that Prehn had lawfully retained his position, finding that the expiration of a term does not create a vacancy. And because there was no vacancy, the governor could not make a new appointment unless he removed Prehn “for cause.” Prehn ultimately resigned last Dec. 30.

That scenario now is unlikely. Commission chair Don Millis, a Republican attorney, told ProPublica Wednesday that “there will be a vote” in the near future to consider the appointment of an administrator.

“If someone didn’t think we should have a vote, and we should rely on the Supreme Court decision in the Prehn case, they could move to adjourn,” he said, but added: “I’m not excited about that. To me it would be avoiding our responsibility if we didn’t act.”

Millis declined to say if he would back Wolfe but said he feared that if the commission did not take a vote “that would only add fuel to the fire of the conspiracy theories that we get hit with.”

He warned, “If we decide no vote is required and Meagan Wolfe keeps her position after July 1, I can guarantee you we’ll be sued and the courts will decide.”

Arguing that Wolfe does not have the confidence of Republicans, Spindell said, “I did tell her that I’m not going to vote for her.” He stressed, however, that he thought she was unfairly blamed for long-standing policies set by the commission.

In a letter Wednesday to clerks statewide, Wolfe acknowledged that “my role here is at risk” but said she preferred that the Legislature act quickly to confirm someone, even if it isn’t her. Still, she made it clear she considers herself the best choice to serve the commission. “It is a fact that if I am not selected for this role, Wisconsin would have a less experienced administrator at the helm,” she wrote.

And she also made clear what she thinks is driving the questions about her future, writing that “enough legislators have fallen prey to false information about my work and the work of this agency that my role here is at risk.”

If the commission does vote on Wolfe, Agard said, she expects Wolfe will secure at least one Republican vote, moving her nomination on to the Senate — and what could be a hostile environment.

Senate President Chris Kapenga, a Trump loyalist, told the Associated Press this week that “there’s no way” Wolfe will be re-confirmed by the Senate. “I will do everything I can to keep her from being reappointed,” he said. “I would be extremely surprised if she had any votes in the caucus.”

In the Senate, the matter could first be considered by the Committee on Shared Revenue, Elections and Consumer Protection — chaired by GOP Sen. Dan Knodl. In the weeks after the 2020 election, Knodl signed on to a letter calling on Vice President Mike Pence to delay certifying the results on Jan. 6.

Spindell already is envisioning a future without Wolfe. He said there is talk of conducting a national search for a new administrator, but Millis said there doesn’t appear to be an appetite among the commissioners for this approach. He noted the commission is pressed for time: Come July 1, the state will be only about 16 months away from a presidential election.

State law restricts who can be appointed as election administrator. Appointees cannot have been a lobbyist or have served in a partisan state or local office. Nor can they have made a contribution to a candidate for partisan state or local office in the 12 months prior to their employment.

If the position is vacant for 45 days, the Joint Committee on Legislative Organization, chaired by Kapenga and GOP Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, can appoint an interim commissioner.

As for Wolfe, Spindell said: “She’s experienced. She’s been on all the various boards. I’m sure she would have no problem getting a job anywhere else.”

Must Read Article on the Jan 6th Investigation

Here’s a really must-read article out this morning from the Post, “FBI resisted opening probe into Trump’s role in Jan. 6 for more than a year.” Unless the reporting comes under serious question, and given who the reporters are I doubt that will be the case, it should be one of the canonical articles required to understand this story. And that story is how it is we only got to the present point in the investigation more than two years after the events of January 6th, 2021.

The key mystery to me is the headline. Unless my brain isn’t working this morning there’s very little in the piece to in any way back it up. FBI Director Chris Wray definitely took a hands-off approach. But the article is quite clear that the main reason for the delay came from top-level appointees at the DOJ — specifically Garland and Monaco and those working under them.

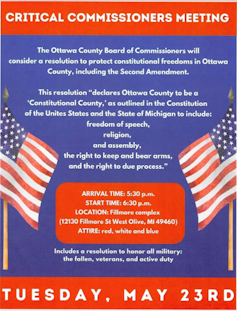

Continue reading “Must Read Article on the Jan 6th Investigation”Conservatives Are Now Trying To Create ‘Constitutional Counties,’ Which Happen To Be Unconstitutional

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

Declaring its community a “constitutional county” on May 23, 2023, the Board of County Commissioners in Ottawa County, Michigan, voted 9-1 not to enforce any law or rule that “restricts the rights of any law-abiding citizen affirmed by the United States Constitution.”

Nor will the county provide aid or resources to any state or federal agency that county officials judge to be infringing on or restricting those rights.

Ottawa is not the first county in Michigan to declare itself a refuge from what its leaders say are anti- or unconstitutional actions undertaken by an overzealous state or federal authority.

Livingston County, also in Michigan, passed a similar resolution in April 2023.

It is not clear how many there are, exactly, but there are also self-designated constitutional counties in Virginia, Texas, Nevada and New York. As a scholar of constitutional theory, I believe more will follow, especially in the roughly 1,100 counties of the nation’s 3,200 counties that have already declared themselves Second Amendment sanctuaries.

But where Second Amendment sanctuaries aim to create havens for gun rights allegedly under siege, the constitutional county movement has a broader agenda.

One of the drafters of the Ottawa Resolution, for example, explained, “As we wrote this resolution … we recognized the need to protect not only Second Amendment rights but all constitutional rights. … We wish to highlight freedoms and constitutional rights which have been violated over the past few years, as well as those currently at risk due to societal and political pressures.” https://www.youtube.com/embed/y2mTYe3qdvA?wmode=transparent&start=0 A news report about the Ottawa County, Michigan, vote to declare itself a ‘constitutional county.’

Why constitutional counties are unconstitutional

Although the two Michigan county resolutions are chiefly symbolic and do little more than encourage – rather than order – local law enforcement authorities and local officials to disregard federal laws they claim are unconstitutional, the dangers they pose to the U.S. constitutional system are substantial.

This way of thinking is profoundly mistaken and undermines Americans’ collective commitment to constitutional democracy.

Declaring oneself a constitutional county undermines the authority of officials authorized to act under the Constitution. I believe it ultimately subverts the authority of the Constitution itself.

When these resolutions instruct county police not to enforce certain laws, such as red flag laws that allow the confiscation of firearms from certain people, they violate Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution. Article 6 declares that the Constitution itself and federal laws are “the supreme Law of the Land” and cannot be overruled or superseded by state laws or laws at lower levels of government.

So any county that claims to nullify federal laws it finds objectionable raises constitutional problems. So, too, do assertions of a right to obstruct federal law or to impede the exercise of federally guaranteed rights and liberties.

In both scenarios, local authorities claim they are under no constitutional obligation to enforce, or to help state or federal officials enforce, laws and regulations that are, in their view, plainly unconstitutional.

On the other hand, if the point is simply to refuse to assist federal officials in enforcing federal law, then that probably is not unconstitutional.

In Printz v. United States, the Supreme Court held in 1997 that federal officials cannot force state and local officials to enforce federal law.

Constitutional principles – or politics?

Among the constitutional liberties Ottawa County officials think are at risk is freedom of religion, which they say is threatened by state and federal diversity requirements in schools. Other rights they say are threatened include those granted by the Second Amendment and parental liberties; they also cite certain kinds of threats to individual liberty, such as COVID-19 mask requirements.

Notably absent were concerns about threats to reproductive autonomy, sexual and gender identities, or public safety endangered by firearms violence. Professions of constitutional fidelity by constitutional county advocates are more often about politics than real concern for the Constitution.

These declarations can be used – and I believe will be used – for pretty much any political agenda and to evade federal laws that some citizens find objectionable.

In doing so, they become little more than political excuses to end-run Article 6 of the Constitution whenever it suits.

Taking the Constitution seriously

It is tempting to applaud any effort by citizens to take the Constitution seriously. As I wrote in my book “Peopling the Constitution,” a healthy and vibrant constitutional democracy requires citizens who understand its promises and take some responsibility for making those promises a reality.

A resolution that simply makes a symbolic claim about federal law or about what the Constitution truly means, and does not order authorities to ignore or violate federal law, does not itself violate the Constitution. Such claims are a vital part of civic and constitutional debate in a healthy constitutional democracy.

But constitutional populism is a double-edged sword. The line between principled constitutional differences of opinion and partisan politics pretending to be a constitutional argument will not always be obvious or easy to discern.

When it substitutes partisanship for discernment, and assertion for argument, the constitutional counties movement undermines the very Constitution it purports to honor.

This story incorporates material from a previous story in The Conversation by the author. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How A Grad Student Uncovered The Largest Known Slave Auction In The US

This article first appeared at ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Sitting at her bedroom desk, nursing a cup of coffee on a quiet Tuesday morning, Lauren Davila scoured digitized old newspapers for slave auction ads. A graduate history student at the College of Charleston, she logged them on a spreadsheet for an internship assignment. It was often tedious work.

She clicked on Feb. 24, 1835, another in a litany of days on which slave trading fueled her home city of Charleston, South Carolina. But on this day, buried in a sea of classified ads for sales of everything from fruit knives and candlesticks to enslaved human beings, Davila made a shocking discovery.

On page 3, fifth column over, 10th advertisement down, she read:

“This day, the 24th instant, and the day following, at the North Side of the Custom-House, at 11 o’clock, will be sold, a very valuable GANG OF NEGROES, accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED.”

She stared at the number: 600.

A sale of 600 people would mark a grim new record — by far.

Until Davila’s discovery, the largest known slave auction in the U.S. was one that was held over two days in 1859 just outside Savannah, Georgia, roughly 100 miles down the Atlantic coast from Davila’s home. At a racetrack just outside the city, an indebted plantation heir sold hundreds of enslaved people. The horrors of that auction have been chronicled in books and articles, including The New York Times’ 1619 Project and “The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History.” Davila grabbed her copy of the latter to double-check the number of people auctioned then.

It was 436, far fewer than the 600 in the ad glowing on her computer screen.

She fired off an email to a mentor, Bernard Powers, the city’s premier Black history expert. Now professor emeritus of history at the College of Charleston, he is founding director of its Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston and board member of the International African American Museum, which will open in Charleston on June 27.

If anyone would know about this sale, she figured, it was Powers.

Yet he too was shocked. He had never heard of it. He knew of no newspaper accounts, no letters written about it between the city’s white denizens.

“The silence of the archives is deafening on this,” he said. “What does that silence tell you? It reinforces how routine this was.”

The auction site rests between a busy intersection in downtown Charleston and the harbor that ushered in about 40% of enslaved Africans hauled into the U.S. In that constrained space, Powers imagined the wails of families ripped apart, the smells, the bellow of an auctioneer.

When Davila emailed him, she also copied Margaret Seidler, a white woman whose discovery of slave traders among her own ancestors led her to work with the college’s Center for the Study of Slavery to financially and otherwise support Davila’s research.

The next day, the three met on Zoom, stunned by her discovery.

“There were a lot of long pauses,” Davila recalled.

It was March 2022. She decided to announce the discovery in her upcoming master’s thesis.

A year later, in April, Davila defended that thesis. She got an A.

She had discovered what appears to be the largest known slave auction in the United States and, with it, a new story in the nation’s history of mass enslavement — about who benefited and who was harmed by such an enormous transaction.

But that story initially presented itself mostly as a great mystery.

The ad Davila found was brief. It yielded almost no details beyond the size of the sale and where it was being held — nothing about who sent the 600 people to auction, where they came from or whose lives were about to be uprooted.

But details survived, it turned out, tucked deep within Southern archives.

In May, Davila shared the ad with ProPublica, the first news outlet to reveal her discovery. A reporter then canvassed the Charleston newspapers leading up to the auction — and unearthed the identity of the rice dynasty responsible for the sale.

The Ball Dynasty

The ad Davila discovered ran in the Charleston Courier on the sale’s opening day. But ads for large auctions were often published for several days, even weeks, ahead of time to drum up interest.

A ProPublica reporter found the original ad for the sale, which ran more than two weeks before the one Davila spotted. Published on Feb. 6, 1835, it revealed that the sale of 600 people was part of the estate auction for John Ball Jr., scion of a slave-owning planter regime. Ball had died the previous year, and now five of his plantations were listed for sale — along with the people enslaved on them.

The Ball family might not be a household name outside of South Carolina, but it is widely known within the state thanks to a descendant named Edward Ball who wrote a bestselling book in 1998 that bared the family’s skeletons — and, with them, those of other Southern slave owners.

“Slaves in the Family” drew considerable acclaim outside of Charleston, including a National Book Award. Black readers, North and South, praised it. But as Ball explained, “It was in white society that the book was controversial.” Among some white Southerners, the horrors of slavery had long gone minimized by a Lost Cause narrative of northern aggression and benevolent slave owners.

Based on his family’s records, Edward Ball described his ancestors as wealthy “rice landlords” who operated a “slave dynasty.” He estimated they enslaved about 4,000 people on their properties over 167 years, placing them among the “oldest and longest” plantation operators in the American South.

John Ball Jr. was a Harvard-educated planter who lived in a three-story brick house in downtown Charleston while operating at least five plantations he owned in the vicinity. By the time malaria killed him at age 51, he enslaved nearly 600 people including valuable drivers, carpenters, coopers and boatmen. His plantations spanned nearly 7,000 acres near the Cooper River, which led to Charleston’s bustling wharves and the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

ProPublica reached out to Edward Ball, who lives in Connecticut, to see if he had come across details about the sale during his research.

He said that 25 years ago when he wrote “Slaves in the Family,” he knew an enormous auction followed Ball Jr.’s death, “and yet I don’t think I contemplated it enough in its specific horror.” He saw the sale in the context of many large slave auctions the Balls orchestrated. Only a generation earlier, the estate of Ball Jr.’s father had sold 367 people.

“It is a kind of summit in its cruelty,” Ball said of the auction of 600 humans. “Families were broken apart, and children were sold from their parents, wives sold from their husbands. It breaks my heart to envision it.”

And it gets worse.

After ProPublica discovered the original ad for the 600-person sale, Seidler, the woman who supported Davila’s research, unearthed another puzzle piece. She found an ad to auction a large group of people enslaved by Keating Simons, the late father of Ball Jr.’s wife, Ann. Simons had died three months after Ball Jr., and the ad announced the sale of 170 people from his estate. They would be auctioned the same week, in the same place, as the 600.

That means over the course of four days — a Tuesday through Friday — Ann Ball’s family put up for sale 770 human beings.

In his book, Edward Ball described how Ann Ball “approached plantation management like a soldier, giving lie to the view that only men had the stomach for the violence of the business.” She once whipped an enslaved woman, whose name was given only as Betty, for not laundering towels to her liking, then sent the woman to the Work House, a city-owned jail where Black people were imprisoned and tortured.

A week before the first auction ad appeared for Ball Jr.’s estate, a friend and business adviser dashed off a letter urging Ann Ball to sell all of her late husband’s properties and be freed of the burden. “It is impossible that you could undertake the management of the whole Estate for another year without great anxiety of mind,” the man wrote in a letter preserved at the South Carolina Historical Society.

Ball did what she wanted.

On Feb. 17, the day her husband’s land properties went to auction, she bought back two plantations, Comingtee and Midway — 3,517 acres in all — to run herself.

A week later, on the opening day of the sale of 600 people, she purchased 191 of them.

More Than Names

In mid-March 1835, the auction house ran a final ad regarding John Ball Jr.’s “gang of negroes.” It advertised “residue” from the sale of 600, a group of about 30 people as yet unsold.

Ann Ball bought them as well.

Given she bought most in family groups, her purchase of 215 people in total spared many traumatic separations, at least for the moment.

As she picked who to purchase, she appears to have prioritized long-standing ties. Several were elderly, based on the low purchase price and their listed names — Old Rachel, Old Lucy, Old Charles.

Many names included on her bills of sale also mirror those recorded on an inventory of John Ball Jr.’s plantations, including Comingtee, where he and Ann had sometimes lived. Among them: Humphrey, Hannah, Celia, Charles, Esther, Daniel, Dorcas, Dye, London, Friday, Jewel, Jacob, Daphne, Cuffee, Carolina, Peggy, Violet and many more.

Most of their names are today just that, names.

But Edward Ball was able to find details about at least one family Ann Ball purchased. A woman named Tenah and her older brother Plenty lived on a plantation a few miles downriver from Comingtee that Ball Jr.’s uncle owned.

Edward Ball figured they came from a family of “blacksmiths, carpenters, seamstresses and other trained workers” who lived apart from the field hands who toiled in stifling, muddy rice plots. Tenah lived with her husband, Adonis, and their two children, Scipio and August. Plenty, who was a carpenter, lived next door with his wife and their three children: Nancy, Cato and Little Plenty.

When the uncle died, he left Tenah, Plenty and their children to John Ball Jr. The two families packed up and moved to Comingtee, then home to more than 100 enslaved people.

Life went on. Tenah gave birth to another child, Binah. Adonis tended animals in the plantation’s barnyard.

Although the families were able to stay together, they nonetheless suffered under enslavement. At one point, an overseer wrote in his weekly report to Ball Jr. that he had Adonis and Tenah whipped because he suspected they had butchered a sheep to add to people’s rations, Edward Ball wrote in his book.

After her husband’s death, Ann Ball’s purchase appears to have kept the two families together, at least many of them. The names Tenah, Adonis, Nancy, Binah, Scipio and Plenty are listed on her receipt from the auction’s opening day.

Yet, hundreds more people who remained for sale from the Ball auction likely “ended up in the transnational traffic to Mississippi and Louisiana,” said Edward Ball, now at work on a book about the domestic slave trade.

He noted that buyers attending East Coast auctions were mostly interstate slave traders who transported Black people to New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, then resold them to owners of cotton plantations. In the early 1800s, cotton had taken over from rice and tobacco as the South’s king crop, fueling demand at plantations across the lower South and creating a mass migration of enslaved people.

Birth of Generational Wealth

Although the sale of 600 people as part of one estate auction appears to be the largest in American history, the volume itself is hardly out of place on the vast scale of the nation’s chattel slavery system

Ethan Kytle, a history professor at California State University, Fresno, noted that the firm auctioning much of Ball’s estate — Jervey, Waring & White — alone advertised sales of 30, 50 or 70 people virtually every day.

“That adds up to 600 pretty quickly,” Kytle said. He and his wife, the historian Blain Roberts, co-wrote “Denmark Vesey’s Garden,” a book that examines what he called the former Confederacy’s “willful amnesia” about slavery, particularly in Charleston, and urges a more honest accounting of it.

Slavery was a form of mass commerce, he said. It made select white families so wealthy and powerful that their surnames still form a sort of social aristocracy in places like Charleston.

Although no evidence has surfaced yet about how much the auction of 600 people enriched the Ball family, the amount Ann Ball paid for about one-third of them is recorded in her bills of sale buried within the boxes and folders of family papers at the South Carolina Historical Society. They show that she doled out $79,855 to purchase 215 people — a sum worth almost $2.8 million today.

The top dollar she paid for a single human was $505. The lowest purchase price was $20, for a person known as Old Peg.

Enslaved people drew widely varied prices depending on age, gender and skills. But assuming other buyers paid something comparable to Ann Ball’s purchase price, an average of $371 per person, the entire auction could have netted in the range of $222,800 — or about $7.7 million today — money then distributed among Ball Jr.’s heirs, including Ann.

They weren’t alone in profiting from this sale. Enslaved people could be bought on credit, so banks that mortgaged the sales made money, too. Firms also insured slaves, for a fee. Newspapers sold slave auction ads. The city of Charleston made money, too, by taxing public auctions. These kinds of profits helped build the foundation of the generational wealth gap that persists even today between Black and white Americans.

Jervey, Waring & White took a cut of the sale as well, enriching the partners’ bank accounts and their social standing.

Although the men orchestrated auctions to sell thousands of enslaved people, James Jervey is remembered as a prominent attorney and bank president who served on his church vestry, a “generous lover of virtue,” as the South Carolina Society described him in an 1845 resolution. A brick mansion in downtown Charleston bears his name.

Morton Waring married the daughter of a former governor. Waring’s family used enslaved laborers to build a three-and-a-half story house that still stands in the middle of downtown. In 2018, country music star Darius Rucker and entrepreneur John McGrath bought it from the local Catholic diocese for $6.25 million.

Alonzo J. White was among the most notorious slave traders in Charleston history. He also served as chairman of the Work House commissioners, a role that required him to report to the city fees garnered from housing and “correction” of enslaved people tortured in the jail.

“Yet, these men were upheld by high society,” Davila said. “They are remembered as these great Christian men of high value.” After John Ball Jr. died, the City Council passed a resolution to express “a high testimonial of respect and esteem for his private worth and public services.”

But for the 600 people sold and their descendants? Only a stark reminder of how America’s entrenched racial wealth gap was born, Davila said, with repercussions still felt today.

Will Rogue House Republicans Cause A Shutdown? A Guide To WTF Is Going On In Congress Right Now

Just a couple weeks ago, President Joe Biden was signing the debt ceiling deal he’d forged with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) into law, prompting a communal sigh of relief as we skirted economic catastrophe.

The peace was short-lived.

Continue reading “Will Rogue House Republicans Cause A Shutdown? A Guide To WTF Is Going On In Congress Right Now “MyPillow Guy Fears Republican Party’s Newfound Embrace Of ‘Ballot Harvesting’ Might Be Part Of A ‘Grand Scheme’

Mike Lindell did not mince his words in a recent phone conversation with Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel.

Continue reading “MyPillow Guy Fears Republican Party’s Newfound Embrace Of ‘Ballot Harvesting’ Might Be Part Of A ‘Grand Scheme’”