When Mohammad Abu-Salha learned that an Oklahoma man had been arrested on suspicion of fatally shooting his Lebanese-American neighbor last week, he felt a sickening sense of déjà vu.

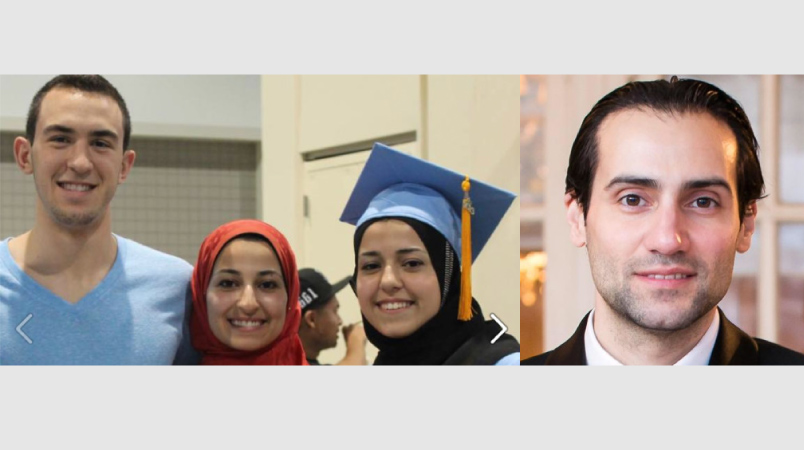

In February 2015, Abu-Salha’s daughters, Yusor and Razan, and his son-in-law, Deah Barakat, were fatally shot, execution-style, in their apartment in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Prosecutors say neighbor Craig Stephen Hicks confessed to the triple homicide.

“We felt it’s a copycat case,” Mohammad Abu-Salha told TPM in a Wednesday phone interview.

Both the Jabaras and Abu-Salhas say their slain loved ones lived in fear of volatile, violent neighbors who harassed them over their ethnicity.

“It’s the same story in detail: the angry neighbor, who is racist, bigoted, mad, picking fights for nothing, and then planning his murder on a day when there was no issue or problem or conflict with the family,” Abu-Salha said of the Aug. 12 shooting of Khalid Jabara in Tulsa.

Stanley Vernon Majors, who already faced felony charges in a September 2015 hit-and-run attack on Jabara’s mother, Haifa, pleaded not guilty Wednesday to charges of first-degree murder and malicious intimidation.

“Khalid Jabara is just like our children,” Abu-Salha said. “He is an innocent victim.”

The cases are not identical, however. Haifa Jabara had taken out a protective order against Majors, which he twice violated, and Tulsa police were aware of the stream of ethnic harassment he allegedly directed towards the family. Barakat and Yusor Abu-Salha, who were married, tried to accommodate Hicks by keeping their concerns to themselves and sharing a map with visitors showing exactly where they could park at their apartment complex in order to avoid provoking his ire.

But both families lived under a cloud of fear, waiting for something to happen.

“Despite the overwhelming evidence we marshalled of a palpable threat of danger and hate facing us on a daily basis, the existing legal mechanisms proved insufficient to protect our beloved Khalid and our mother,” the Jabara family said in a statement, calling Khalid’s murder “preventable.”

Abu-Salha said that he felt his stomach sink upon hearing reports that Barakat had been involved in a shooting in Chapel Hill.

“I knew immediately that my children were dead and that it was Hicks,” he told TPM, saying he had learned from his daughter that Hicks often came to her apartment while armed to yell at her and her husband for perceived slights.

“He told her once that he hated how she looked and how she dressed, and hated who she was,” Abu-Salha said of Yusor, who wore a hijab.

Both families feel that the authorities and the media have devoted insufficient attention to the racial bias they allege motivated their relatives’ killings.

North Carolina and Oklahoma have relatively weak hate crime statutes. In the Tar Heel state, “ethnic intimidation” is a misdemeanor punishable by up to two years in prison and a fine, although the penalty may be raised to a felony. In the Sooner State, “malicious harassment,” with which Majors was charged, qualifies as a misdemeanor punishable on first offense by a year in county jail and a fine of up to $1,000.

Authorities say Majors openly expressed his loathing for the ethnic background of his Lebanese Christian neighbors, calling them “filthy Lebanese” who “throw gay people off the roof” in conversations with police, so it was easier for Tulsa County prosecutors to secure a hate crime charge.

In Chapel Hill, Abu-Salha said that Hicks did not harass Barakat when he lived there with a male friend. Rather, Abu-Salha said Hicks began targeting the couple once his daughter, who wore clothing that reflected her Muslim faith, started coming by the apartment. Hicks also frequently posted Facebook diatribes disparaging religion.

Because of the limitations of North Carolina law, the families of the Chapel Hill victims are pinning their hopes on federal hate crime statutes, which require proof that the defendant explicitly sought out a victim because of racial animus or another distinguishable characteristic. The FBI has not yet determined if it will pursue hate crime charges against Hicks.

Abu-Salha believes that these laws diminish the raw reality of racism and ethnic bias in the United States.

“These laws in my mind are mocking to the victim, when you kill a person and say it’s ethnic harassment or intimidation,” he said.

Regardless of the charges brought against the suspects, both families want to tell the public that the loved ones they lost never provoked their alleged aggressors.

Jabara family friend Rebecca Abou-Chedid, who is acting as their spokeswoman, told TPM she believes it’s inaccurate to characterize the conflict between Majors and the Jabaras as a “neighborly dispute,” given the years of alleged harassment from Majors that she says was one-sided.

In North Carolina, Abu-Salha says he’s still waiting for an apology from law enforcement for issuing a statement on the night of the shooting alleging that Hicks had been motivated by a “parking dispute”—before officially notifying the families of the three victims, he said. None of the victims’ cars were parked in the shared spots that Hicks obsessed over on the night of the shooting.

The Durham District Attorney did not return TPM’s request for comment by press time.

Both Majors’ and Hicks’ cases are tentatively set to go to trial in 2017. In the meantime, the grieving families wait.

“That is our life now,” Abu-Salha said. “It is all a nightmare but we accept our destiny and our fate. We live with dignity, with faith, and a lot of pain.”

Yep, it’s a hate crime even when it’s your neighbor who hates you for your ethnic group or religion or orientation. Although I can see the argument being made that if only Those People wouldn’t try and live around Real Americans there wouldn’t be a problem…

These cases are so sad, but reading the details of the one that just happened in Tulsa is truly shocking. The District Attorney argued that the defendant should be denied bail because of the ongoing violence he had perpetrated against the family and how much of a continuing threat he posed. They granted bail anyway. The family called the police soon after (like the same day) when he started threatening them yet again, and instead of arresting him for violating conditions of bail, they talked to him and left. He then shot their son after the police left. Unfortunately, this is the same pattern that you often see in other kinds of domestic/personal disputes that are handled by the police. They don’t take them seriously enough, they don’t want to get involved.

It will only get worse with the GOP right wing nut jobs and the media. This all can be laid at the feet of the GOP and Trump and the Media especially for not being a better foil against allowing the hate filled outrageous rhetoric to go unchecked. All for ratings.

We are turning into a real live Hunger Games society with the way the media is conducting itself. It is no longer there to inform us but to inflame us.

The FBI needs to do right by these families because this will actually make us unsafe because of the mistreatment and unfairness of how we treat our fellow Americans and those coming here to make a better life.

Please let’s not forget that the judge also canceled the electronic ankle monitor because he wasn’t a threat. If the ankle monitor was still on Majors then when the victim called the police to tell them that Majors had a gun they could have found him.

They sure do love their freedom in Oklahoma and NC. Freedom to be a known racist, carry a gun and threaten ppl

For not being exactly like you.

BTW, Allegra, once again, basic reporting of news without opinion or commentary. Thanks.