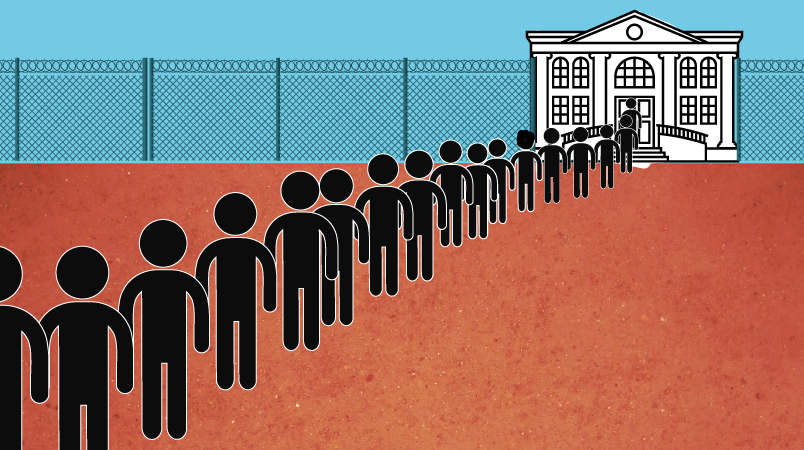

One of the policies President Donald Trump rolled out soon after entering office to chip away at the staggering backlog of cases languishing in the country’s immigration courts appears to be having the opposite effect, immigration judges, attorneys and experts say.

A January executive order directed the Justice Department to temporarily reassign immigration judges to detention facilities, many of which are concentrated in the southwest along the U.S.-Mexico border, to expedite deportations of the undocumented. Last month, Politico published an investigation that found judges were made to abandon overloaded dockets at home for details to sleepy border courts, where some had little to do. DOJ pushed back on that report, insisting that changes had since been made to the program, and earlier this month in a press release boasted that mobilized judges completed about 2,700 more cases than they would have been able to otherwise.

A DOJ official told TPM that the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR) got that figure by using historical data to compare the cases judges were projected to complete at their home courts with those they completed at the surge courts from March-September. But those numbers don’t give a complete picture of the backlog in the immigration courts, according to judges and researchers. They say the types of cases processed in the home and surge courts are entirely different, making for an “apples to oranges” comparison.

The mobilized judges were drawn away specifically from courts where they hear the cases of non-detained immigrants, who may have complex asylum relief claims that can drag on for years. In the surge courts they were assigned to, those judges heard the cases of detained immigrants, who are picked up along the border, often have no legal representation and are more inclined to waive their rights, vastly accelerating the speed at which their cases are processed.

“When you compare completion rates from a non-detained docket to a detained docket you’re going to be comparing apples to oranges,” said National Association of Immigration Judges President Emeritus Dana Marks, who serves as an immigration judge in San Francisco. “And that’s because detained dockets always have a higher volume and a greater percentage of cases where people are not eligible to seek some reprieve from removal or are not inclined to because they don’t want to remain in custody.”

The DOJ official told TPM that the program had a “positive net effect on the pending caseload,” and pointed out that the rate at which the pending caseload increases has slowed this year. Still, the total immigration court backlog grew from some 540,000 cases in January to 632,261 cases by August. According to data obtained by Politico through a Freedom of Information Act request, in the first three months of the program judges postponed around 22,000 cases across the country.

Sue Long, who oversees the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University that tracks the backlog, told TPM that total case “completions are down” and that the DOJ numbers omit critical context.

“You can’t attribute a change to simply posting of judges because a lot more is going on,” Long said. “They’ve been hiring more judges consistently, putting on more and more over the last two years. So you would expect some increase [in the number of cases being completed] because you have more judges.”

There are currently some 330 immigration judges nationwide—a number both the Obama and Trump administrations worked to bolster.

Ashley Huebner, managing attorney at the National Immigration Justice Center’s asylum project, noted that the Obama DOJ also bears responsibility for contributing to the seemingly unsurmountable number of immigration cases by prioritizing recent border crossers from Central America. That meant that immigrants who had waited years to have their cases heard found themselves facing additional months- or years-long delays.

But, anecdotally, advocacy groups and immigration attorneys handling those cases told TPM that the delays they’re seeing now are worse than anything they’ve seen previously. Months after the border surge program was rolled out and apparently tweaked, some lawyers say they’re still receiving little to no notice before the judges handling their cases are abruptly assigned to a border detail, forcing them and their clients to fight the battle to get a hearing all over again.

“We’ll sometimes get word that judge is going to be out on detail to the border or handling a detained case elsewhere in the state,” Atlanta-based immigration attorney Sarah Owings, chapter chair for the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) for Georgia and Alabama, told TPM. “But they don’t tell us the length of deployment or any specific details.”

After months of work preparing documents, obtaining expert and family witnesses, and rehearsing often traumatic narratives with their clients, attorneys say they’ll call the court to confirm a hearing or show up in person to file pre-hearing documents, only to be told by the clerk at the window that their case is no longer on the docket.

“2,700 cases and it was how many judge hours? How much did this cost?” Marks, the immigration judge union spokeswoman, asked. “Our criticism from the association’s perspective was not the sheer number of cases completed alone but also the disruption it caused to the cases left behind and the interests of individuals who’ve had their cases pending for long period of time and often have an interest in getting them resolved because they’re separated from family members or their evidence gets stale.”

Trump’s DOJ has responded to criticisms of the surge program by pointing to a significant uptick in immigration arrests in the country’s interior and in removal orders. But those just add to the overwhelming national court backlog, further burdening an overstretched system.

“In the broad scheme of things it is certainly counterproductive for an efficient running of the courts,” AILA Director of Government Relations Greg Chen said of the border detail surge. “So if the Trump administration is solely focused on deporting people, they’re actually shooting themselves in the foot.”

This post has been updated to indicate that Judge Marks is now president emeritus, rather than president, of the NAIJ.

Allergra’s great lede says it all.

I am great. All the other Presidents were incompetent. I have accomplished more in 9 months than Washington, Lincoln and FDR combined in their entire administrations. I give myself 12 out of 10.

They even suck at evil.

Typical prosecutorial strategy. Go for the low-hanging fruit and punt on the difficult ones. It gives a better completion rate. Lies, damned lies, and statistics.

And that’s what Trump’s doing every time he compares himself to past presidents. Guess who’s the orange?

Trump is totally great, bigly… at failing.