Mexican astronomers running computer simulations believe that rocks blasted upward by the impact of giant meteorites hitting Earth at one time may have sailed past Jupiter and out of the solar system. The astronomers speculate that some of those rocks may have carried with them samples of Earth’s lifeforms to seed terrestrial life on Mars and the moons of Jupiter.

That rocks erupting from the impacts could have made it into space is not controversial. Astronomers think some of them could have gone fast enough to leave the Earth’s gravity and even hit the moon and Venus. Meteorite impacts have occurred throughout the history of the Earth, including times when the Earth teemed with life: indeed, one of the most significant collisions, it is believed, wiped out the dinosaurs.

What is likely to be very controversial is the Mexican astronomers’ theory that life on Earth may have hitch-hiked on the rocks. The theory is based on the notion that all life shares a common origin and spread throughout the cosmos, including Earth, traveling on meteors.

Biological materials, particularly bacteria, can survive in the vacuum of space, subject only to the dangers of radiation, and could last in space a few thousand years, supporters say. According to the theory, biological materials from other worlds could have landed here and, finding hospitable conditions, began evolving.

What the Mexican astronomers propose is the opposite: life from here may have seeded life elsewhere. Debris from the impacts could reach as far as the three most likely places for life outside of Earth: Jupiter’s moons Ganymede and Europa, and early Mars.

The scientists, led by Mauricio Reyes-Ruiz of the Universidad National Autonóma de Mexico in Ensenada, used “numerical simulations” of the flying rocks. They computed the gravitational effects of various bodies in the solar system to plot the potential path of the debris, and added various possible velocities of the ejecta to see how far the rocks would go and where. Arbitrarily, they picked a date, July 6, 1998 to determine positions for the planets.

The researchers said that at the maximum escape velocity they tested, 16.4 kms per second (11 miles a second), the debris would fly out as far as Jupiter and some of it would keep going into interstellar space.

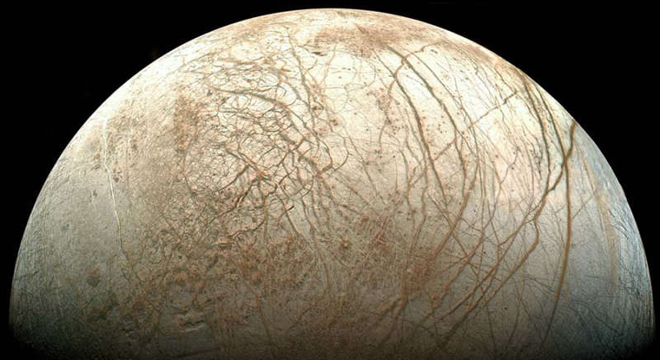

Europa, one of the four Jovian moons discovered by Galileo, is believed to have a thin oxygen atmosphere, and an ocean covered by water ice, ideal for life. Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, is believed to have a salt water ocean beneath its ice as well.

Additionally, early Mars might also have been hospitable to alien invasion, with an atmosphere and running water.

“Definite collisions with Mars and Jupiter are of astrobiological significance, owing to the possible presence of life-sustaining environments in early Mars and in Jupiter’s moons…,” the astronomers conclude.

Other astronomers are not so sure. Their skepticism is based on the speeds needed to eject debris through the atmosphere at velocities high enough to escape the gravitational pull of the sun toward Mars and Jupiter.

“We cannot exclude the possibility of life transferring from Earth to other planets totally. However, it is highly improbable,” said Natalia Artemieva at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona.