Not only is the Earth warming at the high-end of predicted models, but now human produced carbon dioxide emissions are accumulating in greater amounts in the upper reaches of the atmosphere, according to the results of a new study of data captured by a Canadian satellite.

That’s the key finding of a team at the University of Waterloo in Canada and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory’s Space Science Division, relayed in a new paper published Sunday online in the journal Nature Geoscience.

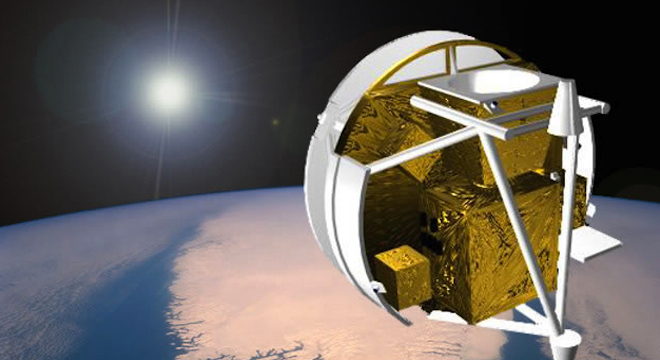

The team analyzed eight-years worth of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) data collected by the Canadian Space Agency’s Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE), a satellite launched in 2003 and bobs around the Earth in a 74 degree orbit, taking spectra measurements and images of the atmosphere.

What the scientists found from looking at the ACE’s data from 2004 through 2012 was troubling: Carbon dioxide levels in the upper atmosphere increased eight percent over the period, from 209 parts per million in 2004 to 225 parts per million in 2012.

Check out the following graph from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL):

As the NRL described in a news release on the findings on Sunday:

“The scientists estimate that the concentration of carbon near 100 km [approximately 62 miles] altitude is increasing at a rate of 23.5 ± 6.3 parts per million (ppm) per decade, which is about 10 ppm/decade faster than predicted by upper atmospheric model simulations.”

At lower altitudes, carbon dioxide emissions make the Earth warmer by trapping sunlight.

But at higher altitudes, the reverse is true: In the mesosphere (between 31 miles and 55 miles up) and the thermosphere (above 55 miles up), carbon dioxide’s density is thinner and a less effective at trapping infrared radiation. In fact, CO2 at these altitudes is something of a heat sink, allowing infrared radiation to escape back out into space.

But this isn’t a good thing. On the contrary, the thinning, cooling trend at this level due to increasing CO2 is likely to have detrimental effects on human spacefaring activity, something of a bitter irony given that a satellite was the reason we know about the increased CO2 levels in the first place. As the U.S. NRL explained:

“The enhanced cooling produced by the increasing CO2 should result in a more contracted thermosphere, where many satellites, including the International Space Station, operate. The contraction of the thermosphere will reduce atmospheric drag on satellites and may have adverse consequences for the already unstable orbital debris environment, because it will slow the rate at which debris burn up in the atmosphere.”

In other words, rather than trapping heat, the increased CO2 levels in the upper atmosphere are likely to result in longer-lasting debris, and thus, a greater proportion of debris over time as humans continue to launch objects into space.

Already, NASA’s Orbital Debris Program, which tracks the overall amount of space junk around the planet, reports that there are at least 500,000 objects orbiting the Earth between 1 and 10 centimeters in size, another 21,000 larger than 10 centimeters. Other scientists have previously warned that Earth is collectively approaching a “tipping point” when it comes to space junk, where one piece of space junk colliding into another could set off a chain reaction of cascading collisions that would make it prohibitively risky to launch anything else into space, a phenomena known as the “Kessler effect” or the “Kessler syndrome” after the scientist who first proposed it in 1978.

Space junk has become such a looming problem that the U.S. NRL has concocted a plan to reduce some of it by shooting clouds of dust into space to increase the drag on debris and bring them plummeting back to Earth, to burn up in the atmosphere. That idea remains just a proposal, for now.