There is no democracy without the vote. There is no democratic legitimacy. There is no rule of law. And yet the vote has been contested throughout our country’s almost 250 year history. We think most often of the march toward universal suffrage rights for all adult citizens: the vote for all white men in the 1820s and 1830s, the extension of voting rights to African-American men in 1870 (15th Amendment) and women in 1920 (19th Amendment). But these de jure enactments have never been the whole story.

By the late 1870s the federal government had withdrawn support for African-American voting rights in the South. By the 1890s African-American voting rights had been all but extinguished throughout the former rebel states through a mix of paramilitary violence, an accommodating federal judiciary and national indifference. But this wasn’t the only change in late 19th century America. Both at the level of politics and elite ideology there was a retreat from democracy. We know this from the attack on the voting rights of so-called “freedmen,” but we also see it in resistance to voting rights for the rapidly rising immigrant population, often made up of newcomers from alien-seeming cultures in Eastern and Southern Europe. As one of the early articles in our series explains, much of the apparatus of voter registration which we now largely take for granted was created in part not to make voting possible but to limit it.

Through much of the middle decades of the 20th century, the battle over voting rights was part of the broader effort to dismantle the system of apartheid which had prevailed in the South since the 1880s and 1890s. Laws like poll taxes, grandfather clauses and the like were struck down in court battles. Congress put the federal government on the side of black suffrage when it passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But the real work of enfranchisement, before and after 1965, happened on the ground in voter registration drives in the South as African-Americans sought to vote in the face of decades of extra-judicial violence which had undergirded and enforced the Jim Crow system.

Today we are kicking off a major project that will continue through the second half of 2018: a ten-part editorial series on voting rights and democracy. I wanted to take a moment to cover some of the history that brought us to today and the reasons why we are undertaking this series. These mid-late 20th century battles over voting rights were not limited to the South nor did they end in 1965. A decade before he was confirmed to serve as an associate justice on the Supreme Court in 1971, William Rehnquist — later Chief Justice from 1986 to 2005 — was challenging the voting eligibility of African-American and Latino voters in Phoenix, Arizona.

In 1982, the Republican National Committee was compelled to enter into a consent decree to allow a federal court to review any “ballot security” measures after it was caught “caging” predominantly African-American and Latino voters in New Jersey.

In 1985, future Attorney General Jeff Sessions, then United States Attorney in the Southern District of Alabama, prosecuted three African-American civil rights activists for voter fraud. Sessions’ chief target was Albert Turner, one of those voting rights activists who ran voter registration drives in the Deep South in the 1960s. Starting in 1965 he was the state director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and an advisor to Martin Luther King Jr. Sessions lost that case and it was the controversy stemming from it more than anything else that doomed his nomination to become a federal judge the following year.

But Sessions’ came amidst a larger transformation of the South from Democratic to Republican dominance. When Sessions’ nomination came up for a vote in 1986, Alabama still had one Democratic senator, Howell Heflin. Later that year, Democrat Richard Shelby defeated Jeremiah Denton, the first Republican Senator elected from Alabama since Reconstruction. But eight years later, when Republicans took control of both houses of Congress for the first time since 1948, Shelby switched parties to become a Republican. Two years later, when Heflin retired, he was replaced by Jeff Sessions.

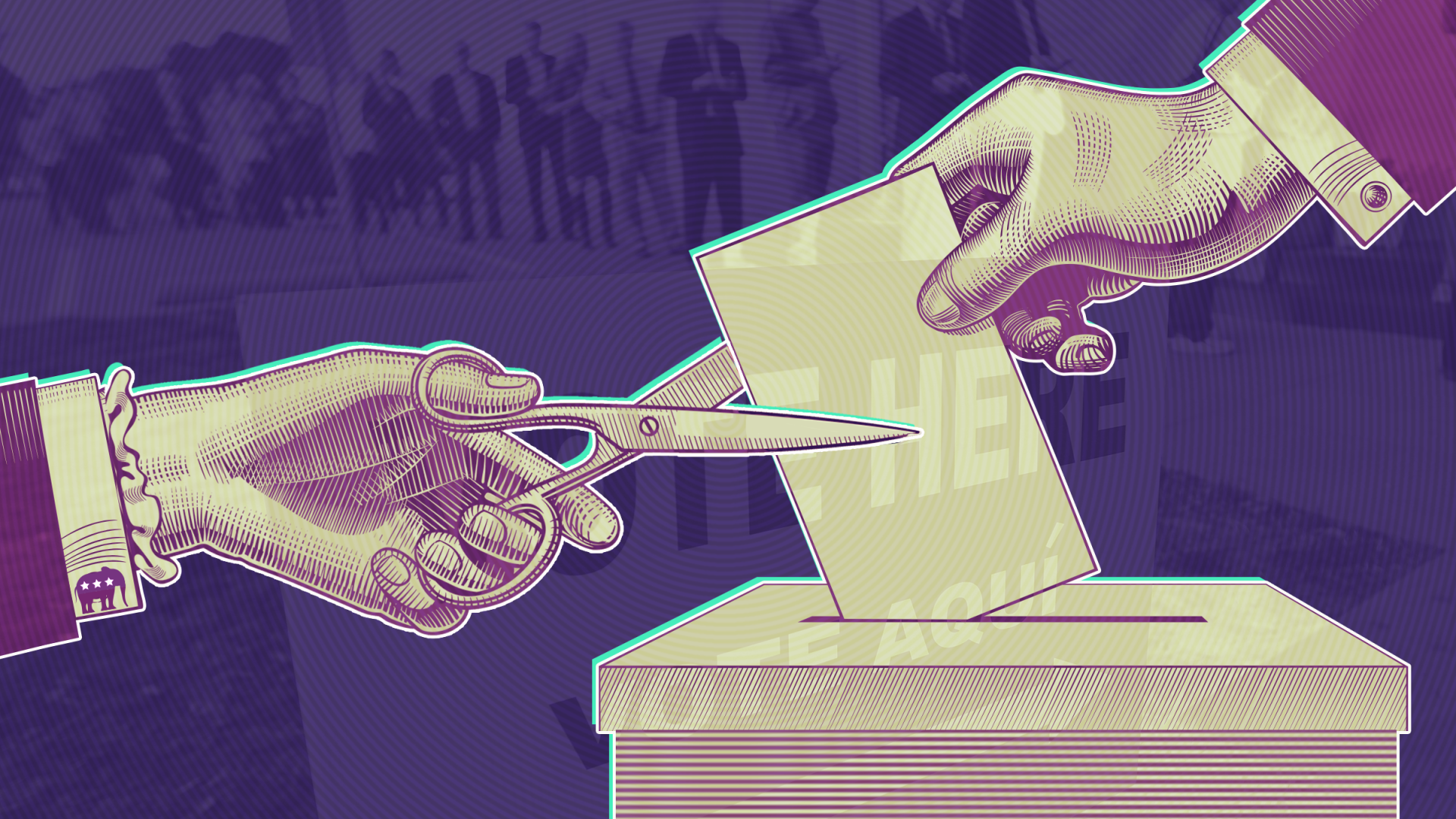

In many ways, today’s battles over voter ID, felon disenfranchisement, gerrymandering and more are simply a continuation of a struggle that has been going for more than two centuries, with a clear line of continuity stretching through the battle for voting rights in the Civil Rights Era South. But there are key differences between past battles and those today, ones we can now see coming to the fore in the last years of the 20th century. Restrictions on voting have long been most effective against the young, racial minorities and the poor — constituencies that, increasingly over the last few decades, have voted for Democrats.

For most of the century after Reconstruction, the United States was an overwhelmingly white country with a relatively small minority of African-Americans (between 10 percent and just over 12.5 percent of the population depending on definition and era). But already by the 1990s there was a rapidly growing Hispanic population as well as rapidly growing populations of people from East Asia and South Asia — changes brought in part by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 which ended racist immigration quotas that had been in place since the Emergency Quota Act of 1921.

Since the middle 1960s African-Americans had voted overwhelmingly for Democrats. But the same wasn’t true of Hispanic voters who voted disproportionately but not overwhelmingly for Democrats. As recently as the early 1990s Asian-Americans were a staunchly Republican group. By the late 1990s however both groups were becoming more solidly Democratic constituencies. In 2012 Hispanics and Asian-Americans voted for Democrats by greater than 2 to 1 margins. Taken together this was part of an increasing racialization of American electoral politics, with non-whites voting Democratic by increasing margins as their percentages of the population grew and the GOP becoming not only overwhelmingly white in demographic terms but increasingly driven by white identity politics.

Generational politics was changing as well. In 1988 George H.W. Bush won voters aged 18-29 by a slightly higher margin (53 percent to 47 percent) than he won voters over 60 (51 percent to 49 percent). That age distribution would be almost unimaginable in today’s politics. In defeat Hillary Clinton won voters under 30 by a 55 percent to 36 percent margin and lost voters over 65 by 45 percent to 52 percent. Four years earlier, Barack Obama won voters under 30 by 60 percent to 37 percent while losing voters over 65 by 44 percent to 56 percent.

These changing demographics created a simple and stark reality. Whereas attacks on voting rights did not used to clearly advantage one party over another, now voting restrictionism clearly advantaged Republicans and disadvantaged Democrats. The 2000 election with its tight margins and county officials peering at dangling chads through magnifying glasses focused Republicans on the importance of every single vote and more ominously how small shifts in the shape of the electorate could have dramatic results. In the late 1990s and early 2000s Republican politics was filled with a growing chorus of claims of “voter fraud,” usually focusing on minority and youth voting, and the need to crack down on voter fraud with new security measures (voter roll purges and voter ID) and increased prosecutions.

During George W. Bush’s first term Karl Rove and the political office at the White House had pushed for greater vigilance for and prosecutions of voter fraud. By 2004 and 2005 the demands for aggressive voter fraud prosecutions were becoming more pointed. One of TPM’s most celebrated stories, the U.S. Attorney Firing Scandal of 2006 and 2007, for which the site became the first digital native website to win one of the country’s top journalism awards, wasn’t really about firing U.S. Attorneys. It was, properly speaking, a voter suppression scandal. Stung by the 2006 Democratic wave election in which Republicans lost control of Congress for the first time in a dozen years, Bush administration political operatives at the White House and the Justice Department concocted a plan to fire a group of United States Attorneys who had resisted the drive to concoct voter fraud prosecutions. The unfolding scandal, which led to the resignation of Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, revealed a network of young Republican voter suppression operatives building a base of political propaganda about alleged voter fraud, largely focused on “inner city” and minority communities, and a legislative agenda of voter restriction. Operatives like Hans von Spakovsky and J. Christian Adams figured prominently in the drama along with Bradley Schlozman, Tim Griffin, Monica Goodling and others.

Two years later Democrats expanded their congressional majorities and elected Barack Obama president. But the changing demographics and Democratic power that election signified intensified Republican focus on laws to restrict voting, especially for minorities and the young, as well as lock in Republican political power. When Republicans reclaimed Congress in 2010 they had even more thoroughgoing success at the state level, success which made possible an aggressive new gerrymandering of Congress and a host of restrictions on voting at the state level. Those trends would continue through 2018. When President Trump created his ill-fated Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity in early 2017 high on his list of appointees were von Spakovsky and Adams, along with arch vote suppression politician Kris Kobach — who was just starting his career in 2007 in Kansas while the U.S. Attorney Firing Scandal was erupting in Washington. All of these trends will now be intensified by what will soon be a Supreme Court with a clear 5-4 far-right majority which is likely to backstop the array of legislative and legal challenges to voting rights which the Court had up until this year at least occasionally viewed with skepticism. Major sections of the Voting Rights Act have already been overturned. The Court appears likely to approve ever more extreme forms of partisan gerrymandering. Today, as we will discuss in one article in this series, there is a move afoot to change the way congressional representation is apportioned which would dramatically reduce representation for areas with large immigrant populations (disproportionately large Democratic urban areas) while expanding the voting power of the redder parts of the country. With a new, conservative justice there is little reason to be confident that the Supreme Court won’t happily approve such a change.

We decided to commission this series on voting rights and democracy early this year because voting rights are more under siege than at any time in most of our lifetimes and because the issue of democracy and voting rights has a particularly salience during a critical election. We can’t say that voting rights today is worse than it was in, say, 1950 when African-Americans across the South were barred from voting. But we are in a period of retrogression which we haven’t seen in more than a century. And it is one that seems likely to get worse before it gets better.

The series we are beginning today is made up of ten articles. They will include historical perspective, as well as extensive reporting on the current moment and policy prescriptions for advancing and securing voting rights against a tide that appears everywhere to be flowing against them. We will have pieces on felon disenfranchisement, gerrymandering, history going back to the 19th century and up through recent decades, voter ID laws, automatic voter registration along with numerous related issues. We will also have reporters in the field covering events as they unfold over the next five months. Our goal is to survey the full breadth of this critical topic, examining the history, the current range of threats and opportunities and, to the extent possible, helping readers understand the scope of the issue, its importance and avenues for positive change over the coming years.

A project of this scope can only be produced with a substantial budget. It involves a major commitment of institutional resources (editors’ time, tech and design resources, planning, etc.) as well as a budget to commission outside writers to produce deeply reported pieces at length. I am very pleased and happy to tell you that The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) signed on to be the exclusive sponsor of this series. As is the case with all of our editorial series, the sponsor has no input or influence over the editorial content. They sign on just knowing the broad subject area, in this case voting rights and democracy. Their sponsorship not only makes this project possible. It also allows us to publish the series entirely outside our Prime paywall as well as in a cleaner, reduced-ad format.

In addition to the 10 pieces in the series, we will be publishing podcast interviews and shorter contributions as well as hosting online discussions to add a participatory dimension to the product. I hope you’ll enjoy and learn from the series and share the contributions widely. We look forward to your responses and feedback and thank you for being readers.

Josh Marshall is Editor and Publisher of Talking Points Memo

Josh Marshall is Editor and Publisher of Talking Points Memo