North Carolina has had a difficult few years in the media. Maybe back in 2014, the headlines about the state’s refusal to expand Medicaid to 500,000 low-income North Carolinians caught your eye. Maybe you heard about the state’s ruthless Voter ID law that, according to a federal appeals court, targeted “African Americans with almost surgical precision.” Or maybe you know of the state’s shameful “bathroom bill,” House Bill 2, that eliminated anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ citizens and mandated that in government buildings, individuals may only use restrooms that correspond to the sex on their birth certificates.

North Carolina’s General Assembly has spent the last six years painting the state such a bright shade of Republican red that it’s difficult to see the vivid shades of Democratic blue that lie in the state’s past and could very possibly resurface in this year’s election, giving the state to Hilary Clinton and electing a new Democratic governor, senator, attorney general, and state supreme court justice. North Carolina was once a leader in the South in its liberal approaches to civil rights and labor disputes, and a national leader in access to and quality of public higher education. But the state remains deeply torn between conservative traditions and progressive ideals. To understand where these progressive ideals originated, there is one man whose story speaks volumes.

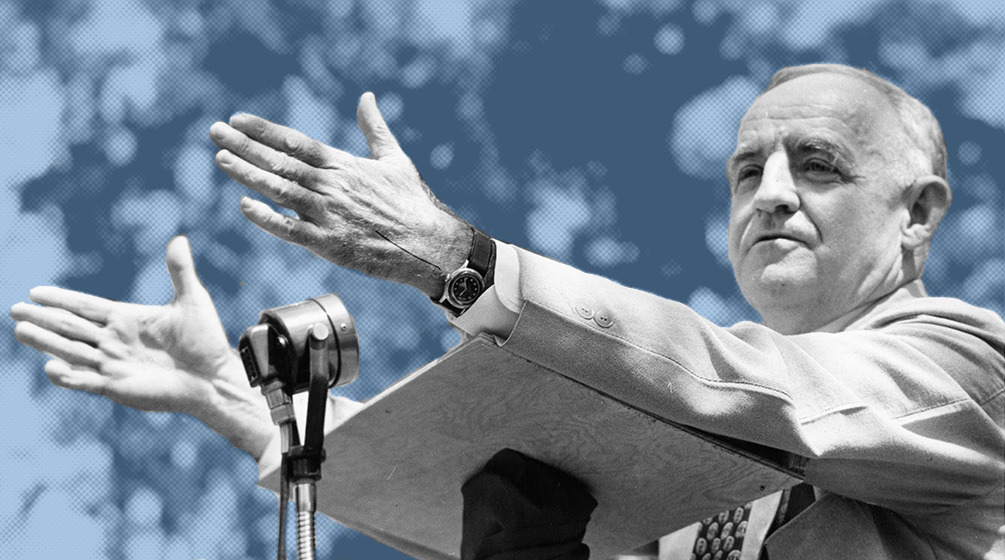

Frank Porter Graham was president of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) for almost twenty years. Graham was an active advocate for civil rights, poverty alleviation, public service, and access to higher education. His liberal reputation bled into that of the university he led, which had been transformed, under his leadership, from a provincial state college into the leading institution in the South.

In 1949, North Carolina’s governor tapped Graham to fill an empty seat in the U.S. Senate, and in the next year, Graham attempted to win election to the seat. Initially favored, Graham was set back by a growing controversy over civil rights and was defeated by an ugly, race-baiting campaign. Over the next 66 years, liberals in the state, including Democratic governors Terry Sanford and Jim Hunt, have continued to battle Republicans like former Senator Jesse Helms and the current governor, Pat McCrory, for the state’s future. But it began with Frank Porter Graham.

Democracy and Education

The child of generations of educators, Graham was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina in 1886 and raised in Charlotte. His father, Alexander Graham, superintendent of the Charlotte Public Schools, brought up his son to value education, not just as a way to improve his own lot in life, but as a way to better society. The Grahams’ family friends were university presidents and professors, school superintendents and state politicians. In this environment, Frank was raised to see the strong connection between democracy and education, public service and higher learning. Though always quite small in stature with extremely poor eyesight, Graham found his first love in baseball and implored his parents up until he left for college to be allowed to pursue the sport professionally (His older brother, Archibald “Moonlight” Graham, briefly played for the New York Giants and was the inspiration for the 1989 film, starring Kevin Costner, Field of Dreams).

Graham entered the University of North Carolina in 1905 as a 5’4’’, 125 pound freshman. He immediately fell under the tutelage of his older cousin, Edward Kidder Graham, a history professor and later president of the university, who was traveling the state promoting the idea that the university had a mission of public service.

Eager to impress his cousin and voracious in his desire to learn more about the relationship between democracy and education, Graham joined just about every student organization that existed on the small campus. As a senior, Graham was the president of the campus YMCA, editor-in-chief of the campus newspaper, head cheerleader, and president of his class. His energy, compassion, and unbridled idealism inspired his peers and impressed his professors and mentors.

In his final speech to the senior class, “The State and The University,” Graham laid out the argument he would make the rest of his career, proclaiming that “the cause of North Carolina is the cause of the University and the cause of the University is the cause of North Carolina.” But Graham’s belief in the university as an instrument of social progress was not widely shared by the state’s elites who feared that democratizing education could endanger their control of the state.

Graham graduated from the University in 1910 at the top of his class, but struggled to find out how he would put to work his varied interests in history, public service, and government. Graham first tried out law school, and when it didn’t quite fit, pursued other graduate work, first in history at Columbia University. Graham moved back to Chapel Hill in 1914 to become the first dean of students, a position interrupted by a two-year stint in the Marines during World War I. Too short, underweight, and with chronic poor eyesight, Graham had to petition the Marines to be admitted as a private.

At the war’s end, Graham again returned to graduate school, this time in search of doctorate in industrialization and labor economics at the University of Chicago, but he left Chicago in 1923 to study at the Graduate School of Economics of the Brooking Institution in Washington and then at the London School of Economics.

Graham never earned his doctorate, but when he returned to UNC in 1925 as an assistant professor of history, students began calling him “Dr. Frank.” Underneath the leadership of his cousin, Edward Kidder Graham, and successor, Harry Woodburn Chase, the university had begun to change from a state college that served the children of the state’s elite into an institution that served a more economically diverse portion of North Carolina’s population. While Graham had been away, new brick dormitories had been constructed, and outreach and extension programs begun. Enrollment numbers were increasing, and there was an urgent need for greater funds to hire faculty.

Graham immediately became involved in a successful statewide lobbying campaign to increase funding for the university. As a member of the Citizens Library Movement and president of the North Carolina Conference for Social Services, Graham also became a tireless speech-maker on behalf of a state-supported system of public libraries and a controversial workman’s compensation law.

In classroom debates, Graham acquainted students from small county seats with new progressive ideas they had rarely encountered. Many of Graham’s students took his ideas to heart when they graduated. For decades, state politics and service organizations were shaped by Graham’s protégés, including future governor Terry Sanford, federal judge Dickson Phillips, and future university president, William Friday.

Outside the walls of the university, Graham gained a reputation as an outspoken liberal. Though Democrats like Graham had influence in state government, representatives of textile manufacturing, the dominant industry in the region, controlled North Carolina’s economy. When a violent strike broke out at a textile mill in Gastonia, North Carolina in 1929 and the governor was forced to call in the national guard to keep order, Graham drafted “An Industrial Bill of Rights,” in which he outlined principles essential for the emergence of “that freedom of personality and equality of opportunity for which this commonwealth was founded.”

The Loray Mill strike. Edward Levinson Collection, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI.

The document, which sought to reduce the prevailing 60-hour work week and improve child labor conditions, outraged many businessmen with investments in the textile industry, as well as their friends in state politics. David Clark, the founding editor of the popular newspaper, The Southern Textile Bulletin, condemned “a small group of radicals [at the university] whom I regard as a cancer upon the institution.” The ringleader was presumably Graham. From his position as a professor of history at UNC, Graham was demonstrating how a progressively driven university could influence issues of national political importance. He had also begun to demonstrate how contentious that influence could be.

University President and Civic Activist

In 1929, Harry Woodburn Chase stepped down from the presidency of UNC, setting off an acrimonious debate across the state about who his successor might be. Governor Cameron Morrison, impressed by Graham’s active support of his administration’s educational policies, lobbied for Graham among other state leaders. Graham expressed concerns that the position would absent him from civic activism and the classroom. However, the next year, at the urging of many of his colleagues, Graham reluctantly accepted the presidency of the University of North Carolina, a position he then held for the next nineteen years.

His presidency coincided with a critical period in American history. Graham guided UNC through the financial drought of the Great Depression, the strain on educational resources through World War II, and into the enrollment boom following the passage of the GI Bill. When Graham became president of the university, it was experiencing formidable growing pains as it struggled to keep financial pace with increasing enrollments. At the end of his tenure, Graham was leading a three-school public university system (including The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina State University, and the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina) that was deeply connected to the state’s governmental organizations, the larger public system of education, and the industrial and intellectual life of the state.

The conservatives in the state’s general assembly, however, shared David Clark’s fear that a risky radical was now in charge of the state’s university. In part a protest of the expanding intellectual liberalism at UNC, they cut the school’s budget by twenty-five percent in 1929-1930 and by another twenty percent in 1930-1931. As the legislature began debating the budget for the 1931-1932 school year, Graham launched a campaign to prevent further cuts.

In the face of dangerously short financial resources, Graham traveled back and forth across the state and to Washington, advocating for grassroots and federal financial support, raising scholarship funds for the many North Carolinians unable to afford a college education. His belief that higher education should be accessible to those who lacked the ability to pay tuition was still quite revolutionary. Though he did not reach his fundraising goals in 1931, Graham became well-known in Washington. When he came calling for federal support again in the late 1930s, he returned to Chapel Hill with enough money to construct much needed new dormitories and academic buildings.

Graham also lent his time and name to a number of radical organizations. In 1938, a group of southern leftists founded the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, the first interracial civil rights advocacy group from the region. While the conference attracted such figures as Eleanor Roosevelt, Hugo Black, C. Vann Woodward, and Gunnar Myrdal, it also attracted a number of attendees from the Communist party, for which it was branded a radical and threatening organization by southern liberals and conservatives alike. Graham was asked to be the keynote speaker and leader of the organization. His opening speech, on the theme “equal and exact justice to all,” generated significant criticism for its endorsement of integration. “The black man is the primary test of American democracy and Christianity,” he said. “Repression is the way of frightened power; freedom is the enlightened way. We take our stand for the Sermon on the Mount, the American Bill of Rights and American democracy.”

Graham was often accused by his critics in North Carolina of being a radical who worked with Communists, but that didn’t bother President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The President relied on Graham as a close advisor on the South and on economic policy. In 1934, Roosevelt appointed him chair of the Advisory Council of the Committee on Economic Security, the first group convened to investigate the feasibility of social security and unemployment insurance. Later, Roosevelt turned to Graham again to lead the Advisory Committee on Economic Conditions In the South out of concern that “the South presents right now the nation’s number one economic problem.”

President Harry S. Truman also looked to Graham. In 1946, a year after he had succeeded Roosevelt, Truman appointed Graham to the President’s Committee on Civil Rights. Graham played a significant role in writing the Committee’s historic report, To Secure These Rights, which appeared in October 1947 and called for the establishment of a permanent Civil Rights Commission, a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission, a Civil Rights Division in the Department of Justice, and the development of federal protections from lynching.

During the time Graham presided over the university, he was constantly under attack from conservative politicians and business leaders, who were indignant over Graham’s use of the presidency of the university to circulate his radical beliefs. Many of them believed Graham was a communist sympathizer. In 1947, a report of the House Un-American Activities Committee found that Graham was “one of those liberals who show a predilection for affiliation with various Communist-inspired front organizations.” The accusation was in part true. Graham was affiliated with a number of organizations that included Communists, but he believed, rather practically, that Communism was not a viable political organization when compared to democracy.

Largely through Graham’s political and social engagements, UNC had earned a reputation as a bastion of liberalism within the politically conservative South. In 1941, the Atlantic Monthly reported that the term liberalism and “the school are as inevitably associated in the Southern Mind as are breakfast grits and bacon.” By the end of Graham’s tenure as president, programs in the humanities and sciences had proliferated at the three UNC system universities, and each university had strengthened ties to the state’s new research and development industries. As president of the University of North Carolina system, Graham had led by example in showing how the university could play a role the civic, industrial, and political life of the state.

The 1950 Senate Race

When Senator J. Melville Broughton died suddenly in March 1949, the task of appointing his successor to the U.S. Senate fell on North Carolina’s newly-elected governor, W. Kerr Scott. Scott needed to find a candidate who would be sympathetic to his own liberal agenda as well as to the national Democratic policies of President Harry S. Truman. He eventually decided on someone outside the Raleigh political network: Frank Porter Graham.

Scott chose Graham largely because he was an outsider and had never sought political office and was unlikely to get in the way of Scott’s own political ambitions. Graham’s supporters and admirers, many of them UNC alumni, were thrilled to see him appointed to the Senate. Here, they believed, Graham’s progressive ideals would reach a wider, more tolerant audience. Others were skeptical. The state’s other Senator, Clyde R. Hoey, who publicly supported Graham, believed that Graham was too idealistic to enact serious policy. Still others saw him as a grave threat to the economic and racial status quo.

After a few months in the Senate, Graham agreed to run for a full four-year term. Though he had strong support from both Governor Scott and President Truman, he still faced a handful of Democratic primary challengers, including Pinetown pig farmer Olla Ray Boyd and former U.S. Senator Robert R. “Our Bob” Reynolds. Neither emerged as serious contenders, and it seemed that Graham, as the incumbent, would easily win his own seat. But in February 1950, Willis Smith, a former Speaker of the state House of Representatives and president of the American Bar Association, entered the race.

Smith, a conservative Democrat and part of an old vanguard of segregationists, went after Graham’s membership on Truman’s Civil Rights Commission. He also accused Graham of being soft on both socialism and communism. Smith began his own campaign by proclaiming, “I do not now nor have I ever belonged to any subversive organizations.” Graham’s campaign, meanwhile, targeted Smith, a corporate lawyer, as unconcerned with working-class needs.

In the primary, Graham came agonizingly close to winning a requisite majority with 48.9 percent of the vote to Smith’s 40.5 percent. While Smith was debating whether or not to call for a runoff, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down three major decisions that affected southern race relations, including Sweatt v. Painter, which required the University of Texas to integrate its law school. The Sweatt decision threatened the end of all-white public universities in the South. Smith’s supporters, voicing the palpable fear of racial integration among white voters, rallied in front of his residence, imploring him to call for a runoff. Smith agreed to do so.

The Smith camp once again accused Graham of being a communist sympathizer and warned white voters that African-Americans that were “bloc-voting” for Graham in the eastern sections of the state. Smith’s supporters printed falsified photographs of Graham’s wife, Marian Drane, dancing with a black man and distributed them across the state. The campaign also widely circulated a flyer, credited to the “Know the Truth Committee,” entitled “White People Wake Up.” It claimed that “Frank Graham Favors the Mingling of the Races” and that “Willis Smith…Will Uphold The Traditions Of The South.”

“Flyer attacking Frank Porter Graham for views on race relations, 1950,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History , accessed October 13, 2016, https://museum.unc.edu/items/show/1089.

But a pandemic of racial fear had swept the state. Smith won the second primary with 52 percent to Graham’s 48 percent, largely because of Graham’s loss of white textile and tobacco workers in the eastern part of the state, where the black population was highest. These were the very same people that Graham had spent his life supporting through labor regulation and public education. Two days after his defeat, Graham told inquiring reporters: “I’m so tired, that I haven’t been able to think.”

Paradoxical Politics

Frank Porter Graham never spoke publicly about his devastating loss in the brutal 1950 U.S. Senate campaign. He went on to have a career in world politics and diplomacy, serving as a United Nations mediator for India and Pakistan during the Kashmir dispute, before retiring in 1967 to Chapel Hill, where he died five years later. His withdrawal from higher education and from state and national politics signaled more than a personal feeling of betrayal. It reflected a deep disillusionment, the result of a statewide disavowal of progress towards racial, economic, and social equality.

The bitterness of the 1950 Senate race would have a profound impact on generations of politicians in the state. After cutting their teeth on the race-baiting of the Smith campaign, future Senator Jesse Helms and his campaign manager and director of the Pioneer Fund, Thomas F. Ellis, would switch parties, becoming two of the state’s most famous and ruthless Republican conservatives. Governor Terry Sanford and Judge Dickson Phillips, two of the “Grahamites” from the liberal side of the party, would hold onto the memory of the 1950 Senate race as they ran and organized progressive coalitions in future elections.

Echoes of the 1950 race have appeared throughout the last half century in Tar Heel politics. In 1984, incumbent Republican Senator Jesse Helms ran against the favored Democrat and former governor, Jim Hunt, beating him by 52 percent to Hunt’s 48 percent, the same margin by which Smith had defeated Graham. In the 1998 liberal Democrat John Edwards, turned the tables by defeating conservative Republican Senator Lauch Faircloth. Six years later, after Edwards had left his seat to run for president, hist Senate seat was reclaimed by a conservative Republican. North Carolina seemed to have returned to the Republican fold.

Lee Churchill, of Raleigh, shows her support of HB2 during a rally at the Halifax Mall in Raleigh, N.C., Monday, April 25, 2016. (Chuck Liddy/The News & Observer via AP)

But then in 2008, North Carolina voted for the Democratic nominee for president for the second time in fifty years (The first had been for a fellow southerner, Jimmy Carter, in 1976). Following that historic vote and the Democratic capture of a senate seat and the governorship, there was a national discussion on whether North Carolina’s state politics had turned away from Republican conservatism for good. But two years after North Carolina went blue for Barack Obama, Republicans took both of North Carolina’s legislative houses for the first time in over a century. Since 2010, North Carolina’s legislature has busied itself with the destruction of the state’s progressive legacy. With the 2012-elected governor, Pat McCrory, as their political partner, the general assembly has dismantled North Carolina’s education, healthcare, and voting systems, law by law.

Though few North Carolinians still remember the defeat of Graham and of his liberal agenda in 1950, the state has relived its effects after the Republican triumph in 2010. Over the past six years, the North Carolina General Assembly refused to expand Medicare, began a social war with its LGBTQ citizens with the passage of the transphobic House Bill 2, passed an income tax that gives significant breaks to the wealthy, expanded rights for gun owners, added restrictions for abortion providers, enacted the most oppressive voter ID law of the last half century (now deemed unconstitutional by a Federal appeals court), and passed a series of state budgets that slashed funding to the UNC system by a total of over a hundred million dollars.

This conservative backlash infuriated many North Carolinians, and has set the stage for a battle this year between progressive Democrats and conservative Republicans. And the prospects for a progressive turnaround look good. Since 2012, the state has added over 300,000 voters, many of them in the metropolitan areas that account for half of the state’s voting population. Most are college-educated and more likely to be Democrats. Political pundits and scholars alike are now arguing that the shifting demographics in North Carolina, led by the growth of liberal-leaning universities, higher tech industries, and high finance, will eventually produce a Democratic majority, undercutting the state’s older conservative voting bloc, which is still largely comprised of voters from the rural parts of the state.

North Carolina’s mutable political identity, split between conservative values and progressive principles, has persisted, but the ground may be shifting – away from the North Carolina of Willis Smith and Pat McCrory and toward that first plowed by Frank Porter Graham.