The Supreme Court’s decision Thursday to uphold President Obama’s signature health care law represented a major triumph for the White House, but will only fuel an already fierce debate about the role and purpose of government on the 2012 campaign trail.

With the law left largely intact by the Supreme Court, the election’s stakes for health care are now clear. Republicans, led by Mitt Romney, have pledged nothing short of a full repeal of the law. Should Romney win office with even narrow Republican control in Congress, the GOP could do grievous damage to the Affordable Care Act using the Senate’s reconciliation process, which requires only a simple majority vote and canot be filibustered.

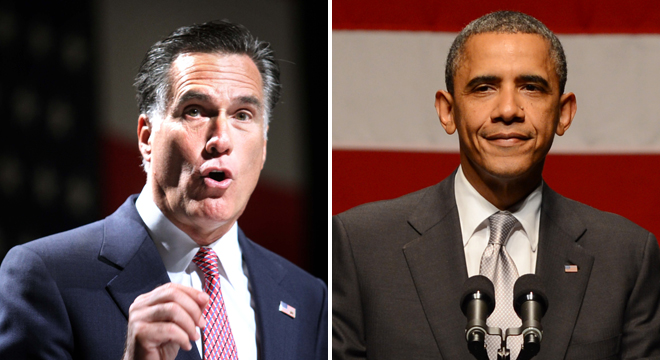

Indeed, Romney said in his response to the ruling Thursday that voters should base their choice for president on opposition to health care reform. “If we want to get rid of ‘Obamacare,’ we’re going to have to replace President Obama,” Romney said in his remarks. “What the court did not do on its last day in session, I will do on my first day if elected president of the United States. And that is I will act to repeal ‘Obamacare.'”

Obama reacted Thursday by reiterating some of the law’s most popular elements, and imploring politicians in Washington to accept the decision and move on. He also insisted the decision represented a victory not because of what it meant for him politically, but because of how it might help ordinary Americans. “Whatever the politics, today’s decision was a victory for people all over this country whose lives are more secure because of this law and the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold it,” Obama said from the White House.

The immediate political impact was dwarfed by the human implications of the ruling, which determined whether the law would expand insurance coverage to over 30 million additional people, including 2.5 million young people already added to their parents’ plans, whether hundreds of millions more would receive significantly more generous benefits and subsidized premiums if needed, and whether millions of Americans with a pre-existing condition — from asthma to cancer — could be denied coverage by an insurance company right when they need it most. But the court’s decision is also a hinge point for the presidential election, which features two candidates who are each closely tied to the law.

The dueling statements represented one of the more ironic turns of the general election. As Obama has often noted, Romney is literally the only other person in America who has signed into law an individual mandate, making it the centerpiece of his health care reforms as governor of Massachusetts.

At the time, the mandate was associated with conservative think tanks. Obama acknowledged Thursday that he too “resisted the idea when I ran for this office” in 2008 but ultimately concluded it was the only way to accomplish his goals for the health care market. Romney expressed support as late as 2009 for a bipartisan bill co-authored by then-Sen. Bob Bennett (R-UT) that included a requirement that Americans maintain insurance.

But despite early indications that a handful of Senate Republicans might work with Democrats on a bill centered on a mandate, the GOP base rebelled against everything associated with the White House’s reforms, successfully making opposition to the requirement the de facto Republican position. Bennett, notably, lost his party’s nomination to the Senate to a conservative challenger who strongly opposed the mandate.

As a result, Romney’s frontrunner status entering the GOP primaries was thrown in doubt and he was forced to tack hard to the right in order to prove his conservative credentials. While never quite disowning his original reforms, he pledged to leave health care largely to individual states during the campaign and repeatedly promised to dismantle the Affordable Care Act entirely.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg even acknowledged Romney’s contributions in enacting a mandate in Massachusetts, in her portion of the ruling upholding the law. “By requiring most residents to obtain insurance … the Commonwealth ensured that insurers would not be left with only the sick as customers,” Ginsburg wrote. “As a result, federal lawmakers observed, Massachusetts succeeded where other States had failed.”

Romney has said that Congress should “replace” it with new health care legislation once the law has been repealed, though he has never said explicitly what a replacement would entail. Romney’s campaign recently confirmed that he does not intend to offer guaranteed coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions, an issue that the ACA’s mandate was designed to fix by bringing in younger and healthier customers into the insurance market to balance out more expensive patients with chronic illnesses.

In his response Thursday, Romney laid out some priorities for a replacement, including making sure “people who want to keep their current insurance will be able to do so” and “[making] sure that those people who have pre-existing conditions know that they will be able to be insured, and they will not lose their insurance” — the latter of which is one of the Affordable Care Act’s most popular provisions.

With the bill’s fate finally clear, Romney will be under heavy pressure to offer more detail about a credible alternative. National Republicans, while largely united behind repealing the entire bill, are heavily divided over how much of the ACA they would want to reproduce afterward. Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) reassured conservatives this week that their only focus through the election is to eliminate every last vestige of the existing legislation, not negotiate its replacement.