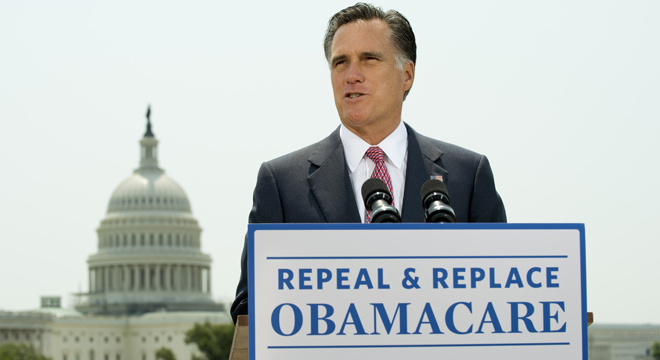

Mitt Romney and President Obama may be the most sharply divided nominees of their generation on the issues of the day, but they’re also the only two people in the country to sign an individual health care mandate into law. The difference is that Obama has a party that’s willing to defend him.

Romney boldly predicted other governors would follow right behind him when he jumped into the universal health care pool in 2006. None did — until Obama came along. The president’s embrace of the mandate prompted Republicans who previously had supported the idea to flee. Romney, on the other hand, refused to condemn his signature achievement, making him the last prominent Republican holding the bag. The result is a mess for Team Romney as the former governor’s campaign is forced to defend his signature law on its own, without a single like-minded surrogate to back him up.

For some time, Romney downplayed the resemblance by attacking the Affordable Care Act as an unconstitutional intrusion on states’ rights. But now that it’s the law of the land, Republicans are moving on to parsing its policy details, where the similarities are much harder to gloss over. Their first big post-ruling attack line revolved around Chief Justice John Roberts’ classification of the mandate as a tax. The mandate, therefore, was a tax hike on the middle class, Republicans charged. Romney adviser Eric Ferhnstrom quickly broke with the pack — since embracing the line would mean admitting that his boss’s own mandate was a tax hike as well.

Such breaks between Romney and the rest of the party will be tough to avoid so long as health care remains a dominant 2012 issue. Whether it’s the nature of the mandate, the utility of state exchanges or the worthiness of making universal coverage a health care goal, Romney’s law is a millstone around a surrogate’s neck.

“You’ve got dozens of people recently endorsing [a mandate] and you can’t line one up to support it now,” MIT professor Jonathan Gruber, who helped craft both the Massachusetts and federal laws, told TPM. “It says worlds about how they think about policy, which is that they only think about politics.”

Top surrogates have yet to find a coherent explanation for why they nominated Mr. Individual Mandate himself if they hate the policy so much.

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker tried to squirm out of questions about Romney’s Massachusetts law this week by praising it as an example for the nation — that is, an example of what not to do, ever, under any circumstances, no matter what.

“We learned looking at that state, Massachusetts is a good example, we learned from what we found from our actuarial assessment that we did this past year that it was not a good measure for the state of Wisconsin,” Walker told CBS on Sunday.

This isn’t a new problem. South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, a top Romney surrogate, made clear from the day she endorsed him that her support was contingent on a promise to keep Rommneycare far, far away from her state.

“He is very aware that that is not something I want in South Carolina,” Haley told CNN at the time.

These awkward exchanges aren’t going away, either. The Obama campaign is all too happy to put Republicans on the spot about Romney’s Massachusetts law. Adding insult to injury for Republicans: Romney’s GOP primary opponents predicted precisely this uncomfortable scenario predicted precisely this uncomfortable scenario.

The GOP’s universal disgust with anything linked to the ACA raises the question whether there’s anyone Romney can trot out to take his side on the Massachusetts law. Perhaps, Newt Gingrich, who hailed the passage of Romney’s law as a landmark moment for health care at the time? Nope, that ship sailed during the primaries.

“You watched [Romneycare] go to work,” Gingrich told CNN in December. “Where Romney and I are different is, I concluded it doesn’t work. He still defends it.”

The only other governor to lend public backing to a Massachusetts-style reform bill was Arnold Schwarzenegger, and he’s persona non grata within the party for a variety of reasons. The Republican senators who joined Romney in supporting the mandate-driven Wyden-Bennett bill in 2009 have either abandoned their position or been ousted in primaries.

The best he can hope for is Sen. Scott Brown (R-MA), who voted for Romney’s bill as a state legislator and shares Fehrnstrom as an adviser. But he’s in a tough fight of his own against Elizabeth Warren that requires him to stay out of the national GOP debate as much as possible.

The GOP can’t expect to win their argument while they leave Romney out to dry, said Republican strategist Brad Blakeman, even if the Massachusetts law is a “diversion” in his eyes.

“The GOP better defend him if he has a shot to defeat Obama based on the largest tax increase in U.S. history,” he said. “They should defend his record as governor and pivot to the national issue of health care and what he plans and promises as candidate.”