When the Supreme Court hears oral arguments Wednesday on the Voting Rights Act, opponents will argue that a centerpiece of the law aimed at letting the federal government proactively thwart attempts at voter discrimination has outlived its validity.

“The only reason Section 5 was originally justified and upheld by the courts was because of Jim Crow — the unusual circumstances at the time in terms of voter disenfranchisement,” Ilya Shapiro, the editor-in-chief of the Cato Supreme Court Review who filed an amicus brief in the case, told TPM. “I don’t think there’s a way to justify Section 5 anymore.”

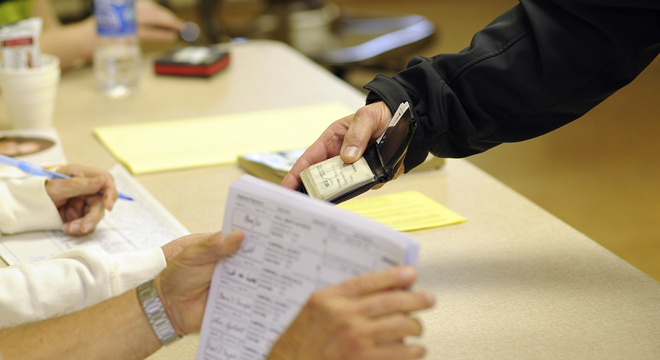

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act requires state and local governments across 16 states — mostly in the South — to seek preclearance from the Justice Department or a federal court before making any changes to their laws which affect voting. Shapiro said the point of the lawsuit is that residents in each of the covered jurisdictions are being treated unfairly.

“There’s a tremendous imposition of paperwork and litigation costs on these jurisdictions to making voting changes — even miniscule things like moving a polling place from a park to a school,” he said, pointing out that the vast majority of proposed changes get approved. “All this would say is that you would no longer have a presumption that everything that states in the covered areas do is unconstitutional.”

The case carries important implications, not merely for voting rights in the mostly southern regions targeted by Section 5 but also for the conservative legal movement’s longstanding efforts to limit the scope of federal power.

The lead plaintiff, Shelby County of Alabama, argues that although Section 5 was justified at the time to correct the evils of racism, it now lacks constitutional basis because the regions it singles out have experienced a dramatic rise in minority voter participation and because outright discriminatory laws like literacy tests are outlawed.

“Section 5 exacts a heavy, unprecedented federalism cost,” Shelby County wrote in its brief, “by forbidding the implementation of all voting changes in jurisdictions identified by Section 4(b) until federal officials are satisfied that the changes do not undermine minority voting rights.” Without more evidence that those parts of the country continue to systematically disenfranchise minority voters, “Section 5’s federalism cost is too great,” it said.

Congress begs to differ. In 2006, a Republican-led Congress reauthorized the Voting Rights Act, including Section 5, after it determined that “vestiges of discrimination in voting continue to exist as demonstrated by second generation barriers constructed to prevent minority voters from fully participating in the electoral process.”

Defenders of the law argue that Section 5 remains an essential tool to proactively combat voter disenfranchisement. They point to various instances in recent years where the Justice Department has denied preclearance for voting changes to covered regions, and will contend that efforts at voter discrimination are more routine in those areas than in the rest of the country. They also note that Congress, not the courts, is tasked with enforcing the 15th Amendment.

Section 5 has been validated four times by the Supreme Court, in 1966, 1973, 1980 and 1999, noting that the 15th Amendment authorizes Congress to enforce the ban on discriminatory voting laws. But the ideological makeup of today’s Court means another victory will be a tough slog for defenders, as five justices have sympathized with the notion that Section 5 is unfair.

“Things have changed in the South,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in 2009.

Shapiro expects the Court to invalidate Section 5, or at least Section 4(b), which specifies the jurisdictions that are covered. Either would be a victory, he says, seeing “no plausible circumstance” where Congress will be able to justify why any regions require preclearance.

“The bigger picture,” he said, “is that this would get us to a state of normalcy in the sense of the proper relationship between the federal and state governments.”