The German Aerospace Center has located the final resting place of its defunct ROSAT satellite that crashed to Earth in an uncontrolled free-fall on Saturday night: The Bay of Bengal.

That’s a welcome relief for the agency as well as the citizens of two heavily-populated Chinese cities, Chongqing and Chengdu, which were also in the path of the satellite’s descent.

Still, though, it remains an open question whether any debris survived the reentry.

As the German Aerospace Center (DLR) explained in an update posted on its English-language website:

On 23 October 2011 at 03:50 CEST, the German research satellite ROSAT re-entered the atmosphere over the Bay of Bengal; it is not known whether any parts of the satellite reached Earth’s surface. Determination of the time and location of re-entry was based on the evaluation of data provided by international partners, including the USA.

“With the re-entry of ROSAT, one of the most successful German scientific space missions has been brought to its ultimate conclusion. The dedication of all those involved at DLR and our national and international partners was exemplary; they are all deserving of my sincere thank you,” said Johann-Dietrich Wörner, Chairman of the DLR Executive Board.

That confirms the predictions of Discovery News reporter Ian O’Neill, who on Monday suggested that the satellite ended up in the Bay of Bengal.

The ROSAT satellite, which had been launched in 1990 and successfully conducted an x-ray telescopic survey of the entire sky before targeting specific celestial objects such as comets and black holes, had been rendered useless by an accident in 1998, wherein its camera lens had been erroneously pointed directly at the Sun, causing permanent damage.

The 2.4-ton satellite was officially retired in 1999, but continued to orbit the Earth in a decaying orbit. It was originally due to crash back to the Earth’s surface in December, but increased solar activity heated the Earth’s atmosphere causing it to expand, boosting the satellite’s rate of acceleration up to Saturday, October 22.

As in the case of NASA’s free-falling, decommissioned UARS satellite – which crashed harmlessly into the Pacific Ocean about a month prior to ROSAT, on September 24 – observers on the ground had next to no idea where the satellite would actually land due to the fact that it was orbiting the Earth once every 90 minutes prior to its reentry. As the DLR explained:

Even just one day before the spacecraft leaves orbit, the timing can only be predicted to within ±5 hours, or 6.5 orbits of Earth. Since the Earth rotates below the orbit of the satellite, the area on the Earth’s surface (referred to as the ‘ground track’ of the satellite) that might be affected by falling debris following re-entry changes from one orbit to the next. From this information, it is clear that no statement can be made about the precise location of re-entry or any potential ground impact.

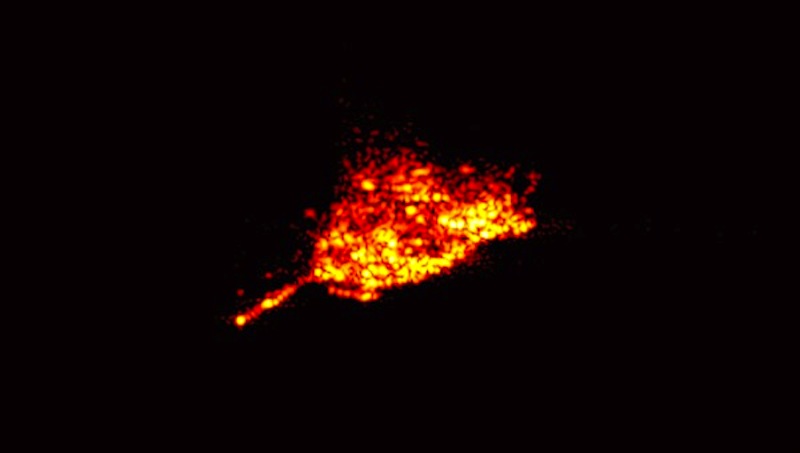

Despite that, the DLR was able to produce some striking imagery of ROSAT reentering in a fiery blaze of glory, such as the photo at the top of this post, which was generated from data obtained by a network of monitoring stations around the globe, including the Tracking and Imaging RAdar (TIRA) at the Fraunhofer Institute for High Frequency Physics and Radar Techniques in Wachtberg, near Bonn, Germany.

ROSAT was also captured in orbit above earth, prior to its free fall, by French amateur astrophotographer Thierry Legault, who used his own homemade satellite tracker and telescope camera to snap haunting, blurry, ultrasound-like images of the tiny satellite tumbling alone in low-earth orbit.

And although nobody was able to capture video of ROSAT burning up in re-entry, aerospace software company Analytical Graphics, Inc. (AGI) did create a simulation of the event using its own analysis tools, including “a Two Line Element (TLE) file to define an initial state for each spacecraft” and “relevant force models to get an estimate of the reentries,” according to AGI media relations manager Joanne Welsh.

“While a high level of uncertainty remained regarding the actual time and location of the reentries (as was stated by the spacecraft operators themselves), our analysis provided a representative model to create a visual representation for what the reentries would look like,” Welsh told TPM via email.