The other day, I pointed out the pink sunset between the cluster of bare winter trees behind our house to my five-year-old daughter, and she turned to me, her face blank and said, “Is that real?”

“What do you mean, honey? It’s the sunset.”

“No, I mean is that fake, like is this something we see on TV, or is it actually happening?”

I thought I’d done a better-than-average job striking a tech balance for my kids—I take them on hikes, craft illegible chalk drawings on the sidewalk, have a no iPhone rule for the beach—but my daughter’s confusion bothered me. Yes, she’s five. Yes, kids that age sometimes confuse what they see on TV and what’s real. You can’t touch a sunset, so I couldn’t explain it to her in the physical way, but I emphasized that we weren’t staring at a screen. That what she saw in front of her eyes was in fact, real life.

I thought about this moment when I read Alison Slater Tate’s Washington Post article last week about what it’s like being a parent in the age of iEverything. Tate groans about how challenging it is to get her kids to look up from their phones just to acknowledge nature. “We can try as hard as we want to push back and to carve space into our children’s lives for treehouses and puzzles and Waldorf-style dolls,” she writes, “but in the end, our children will grow up with the whole world at their fingertips, courtesy of a touch screen, and they will have to learn how to find the balance between their cyber and real worlds.”

Tate’s essay is the latest in a wave of modern critiques about how the onslaught of our digital world will be the end of us. This week, Information Age’s headline blared that the digital reborns are taking on the digital natives. This doomsday map illustrates how humanity keeps discovering brilliant new ways to destroy itself. And if Newsweek’s threat of Cyberwar doesn’t want to make you escape to a computerless cabin in the woods, I don’t know what will. It’s a point that’s made over and over and over again.

There’s part of me that sympathizes, but something about the panic rubs me the wrong way. This constant commentary isn’t just unsettling, it’s fear-provoking. It’s like we’re living a written history, a techno play-by-play, instead of what Matthew McConaughey would recommend (which, I would never say in a million years…okay fine, maybe once): Just Keep Livin’.

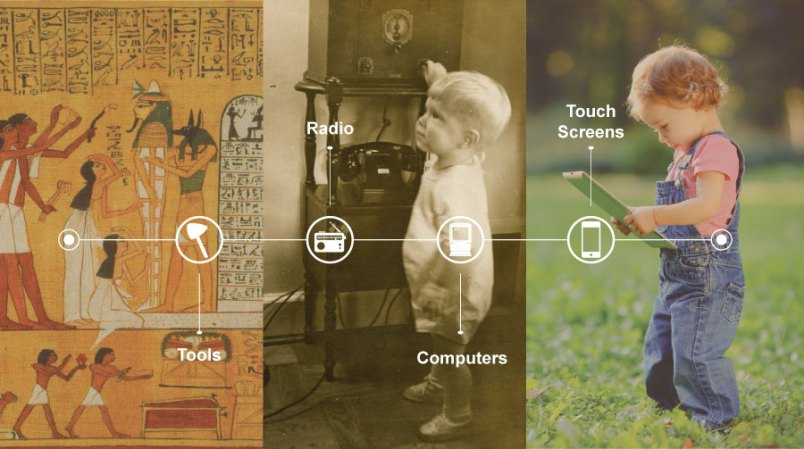

Even though our technology is new, our anxiety about it is not. And it’s this same anxiety that connects us to the growth and innovation of every other era of human history.

Each generation has a story to tell about a gadget that seemed modern and crisp and also utterly daunting. When my mother watched Milton Berle on her set in her two-family house in Brooklyn, it was the first television set on her block. I had the first Atari in my neighborhood, which was why my cute neighbor wanted to hang out at my house. All you have to do is watch “Downton Abbey” to see how uncomfortable tech advances have made us in the past 100 years—in a recent episode, Lord Grantham and Mr. Carson melted down when Lord Grantham’s much younger niece asked for a “wireless” (a radio) to listen to a broadcast of the king’s speech. “I find the whole idea kind of a thief of life,” Grantham said. “That people should waste hours huddled around a wooden box, babbling inanities at them from somewhere else.”

Look at big-impact inventions: Technology writer George Dyson credits cement as a crucial first-millennium innovation, telling the Atlantic that “it was the foundation of civilization as we know it—most of which would collapse without it.” But isn’t it possible some Egyptians were all, Hey, what about limestone? Our society will never be the same.

Granted, the changes of the past five years have moved quicker than any time in history. My son, age 11, didn’t have the luxury of playing on an iPhone when he was a toddler, but my daughter, five years younger than he, already knew how to use a few of the early apps by the time she was 18 months old. Tech has had such tremendous breakthroughs since 2010—tablets, motion sensor game consoles, agricultural drones and brain mapping—that the ones screaming “Remember when?” are practically newborn babies.

But even though it’s faster now, our awe over technology allows us to tap into an intrinsic part of human history. In a way, that’s strangely comforting. My son constantly reminds me, You know nothing about life because you grew up in the seventies, but in the very near future, someone is going to dismissively say to him, You’re from the aughts. It’s all different now.

In the end, though, nature still has a magnetic pull. Just the other day, “War Games,” the OG of hacker movies, was on TV. A pivotal scene shows Dr. Stephen Falken, a character based on Stephen Hawking, learning that the computer he created for NORAD—the kind of intelligent computer that can think for itself—is about to launch Global Thermal Nuclear War and there’s nothing anyone can do to stop it. Just before Falken helps save the world, he lectures Matthew Broderick and his girlfriend about human evolution:

Once upon a time, there lived a magnificent race of animals that dominated the world through age after age. They ran, they swam, and they fought and they flew, until suddenly, quite recently, they disappeared. Nature just gave up and started again. We weren’t even apes then. We were just these smart little rodents hiding in the rocks. And when we go, nature will start over. With the bees, probably. Nature knows when to give up.

Until our technologies destroy it, nature will endure. We’ll always be forced to look up from Twitter or stop scrolling through whitewashed Swedish homes on Instagram to catch a sunset or a full moon. Even my daughter’s question seems much more innocent in this context—less spawned from the evils of technology than child-like curiosity. “This is so beautiful,” she seemed to be saying. “How can it be real?”

Hayley Krischer is a freelance writer based in New Jersey. Her work has appeared in The Toast, The Hairpin, Salon, The New York Times and other publications. You can find her on Twitter.

I loved the 5 year old’s question, but I am not so sure I am down with the idea that technology is changing faster and in more important ways now than in the past. Whenever I hear that I think of my grandparents who watched the world move from horses to automobiles, from trains to airplanes and from oil lamps to electricity. Think about how indoor plumbing and the steel bed frame changed the world. Think about modern water treatment and waste removal. Those changes were really world changing… They all happened about the same time during the early part of the 20th century.

In my own lifetime, I remember when television came to my neighborhood and my mother worried my brothers and I would never spend time outdoors. My mother talked about the impact of refrigerators, washing machines and dryers on her life. World changing.I remember watching America put several men on the moon way back in the late 60s and early 70s. I also remember my first time flying on a jet airplane to someplace. Today I can and do spend a part of each month 1500 miles away. I leave Monday morning, work all week and return home Friday evening. What about all the advances in medicine? They have been going on for at least a century. Why is anybody afraid of technological change.

An IPhone isn’t a great world shattering advance when compared to all the amazing things that have been invented over the last 100-150 years. If anything the world isn’t changing as fast as we thought it would when I was young. I still want my hoverboard.

Sorry, but I don’t understand the headline. It’s clever I suppose, but nothing in the piece supports the premise. We seem to be grasping at technology primarily because it’s new and we’re afraid of being left behind (apparently). I don’t see many people resisting it’s allure, or actively concerned about how it may change us.

I have to agree with ronbyers. My take is that we have become so self-centered and ignorant of history that we are all but unaware of the difference that “technology” has been making in our lives for several centuries.

The toys now are different, and smaller. But not necessarily life-changing like electricity or indoor plumbing, or so many other things. The wide availability of the Internet is life changing - an iPhone is just a toy. A very refined and well executed design for a toy, but still just a toy; it was not the original mobile phone (and even that pales beside electricity and indoor plumbing as a life changing technology).

Yup!

I would love to see what the Mother would say to her 5 year old child when asked. ''Mommy where does the poop go?"

~OGD~

The problem I see here is a rather naive way of viewing technology. Given that it is driven almost entirely by entities that seek to profit from eyeballs on screens–usually through some form of entertainment or “edutainment” in a school environment. They wish us to give up our privacy, placing more and more of our lives on-line so that they can commodify us into things to be sold to advertisers. De la Boetie would have been appalled at our voluntary servitude.

Meanwhile, what is the end result? Distracted young people who walk around as if a smartphone were part of their anatomy–heads down, elbows in, texting furiously away while the world passes them by. Fahrenheit 451 indeed.

If you don’t believe me, then see what Dr. William Cronin from the U of Wisconsin had to say a few years ago as President of the American Historical Association:

“In a manically multitasking world where even e-mail takes too long to read, where texts and tweets and Facebook postings have become dominant forms of communication, reading itself is more at risk than many of us realize. Or, to be more precise, long-form reading is at risk: the ability to concentrate and sustain one’s attention on arguments and narratives for many hours and many thousands of words. I have come to think of this as the Anna Karenina problem: will students twenty years from now be able to read novels like Tolstoy’s that are among the greatest works of world literature but that require dozens of hours to be meaningfully experienced? And if a novel as potent as Anna lies beyond reach, what does that imply for complex historical monographs that are in many ways even more challenging in the demands they make on readers?”

Teach your kids to love reading. Limit the screens as much as possible. Make in-person social engagement with their peers a habit. Challenge them not to fall into the same patterns as their friends. Help them engage with Nature, art, architecture and music.

God forbid, this might even save you some cash on your electric bill…

I think the last world changing technology was the internet. People don’t realize the internet is 46 years old. Originally it linked mainframes. PCs were linked by the world wide web, The world wide web is 26 years old. Of course, since then various wireless devices have been hung on the internet. The idea of wireless comes to us from Tesla.

Can you think of any world changing technology after the internet and its son the www? Everything since has simply been to speed things up.