Edward Forchion is the platonic ideal of a stoner. There’s the shoulder-length dreads. The Ford van airbrushed with Little Shop Of Horrors-sized buds. When he broke his leg this summer, he got a bright green cast. Later, he fixed a bowl to its knee and strung a tube through the leg. Ta-da! Cast bong.

“I use the stoner image to my advantages,” says the 50-year-old activist, who has represented himself in two New Jersey drug cases. His preferred moniker is NJWeedman, and the persona doesn’t just help him score free tune-ups on his “Weedmobil,” he says. It also helps him spread his message.

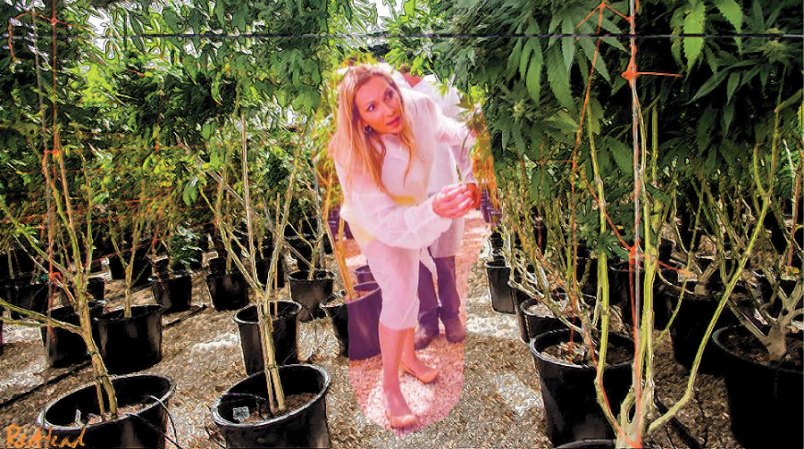

Cheryl Shuman is a weed activist, too, though she recently traded in a Ferrari for a Prius. A recent profile called her “the Cannabis Queen of Beverly Hills.” Pictures of celebrities—Steven Tyler, Mario Lopez, Tommy Chong—pepper the websites of her ventures Haute Vape (a Lilly Pulitzer-hued vape pen) and Cannalebrity (a magazine in development). “Media people want to talk the lifestyle of the rich and famous,” the 54 year old tells me. “They’re not interested in stereotypical stoners.”

Forchion and Shuman are both cancer survivors. Avid social media users. Cultivators not just of weed, but of personas that sit at the extremes of the movement. They get along, too—the year before last, they smoked a joint together at the Seattle Hempfest. Yet the factions they represent are increasingly at odds. Spend enough time listening, and it starts to sound like a culture war.

Edward Forchion

Colorado and Washington State are the battlefields. Since 2012, when those states legalized recreational weed, everyone from growers and bankers to chefs and reality TV stars have rushed for a piece of THC-butter pie, now worth $2.3 billion according to investment firm ArcView Group. The culture around weed is diversifying. But in the media, there’s a new hegemony: the lifestyles of bougie, mostly white entrepreneurs. Think weddings with weed leaf bouquets, critics who specialize in reviewing strains, and, reportedly as of this week, a SkinnyGirl marijuana engineered to prevent munchies.

Lately, though, a backlash has been mounting. “We got ripped apart,” says Olivia Mannix, the 25-year-old cofounder of Cannabrand, of the criticism she endured after a New York Times profile of her company came out in October. The paper described her and her partner, Jennifer DeFalco, as a “new breed of entrepreneur in Colorado—young, ambitious and often female—trying to reach a more sophisticated clientele.” The controversy centered on this quote: “We’re weeding out the stoners.” It set the 420 internet ablaze, and the agency lost a client the day after the story came out. “People misunderstood us,” says Mannix.

The debate over weed’s image isn’t just superficial. Underneath labels of suits and stoners, hippie and yuppie, recreational and medicinal lie tricky questions. What happens when a drug defined for decades by its rebel mythology suddenly loses what made it subversive? Will legal weed retain a culture of its own, or will it become just another substance in our medicine cabinets, accessible to more yet dearer to few?

These questions aren’t pressing for Cornell Hood II. He’s in jail. Four and a half years ago, he received a life sentence for a nonviolent marijuana crime, with no possibility of parole.

“I think it is cool people in some states can smoke weed legally,” he told me from a phone in his dormitory at Jackson, Louisiana’s Dixon Correctional Institute. “I don’t hate on the situation.” On the other hand, “it’s foul that in other parts you can be convicted and have your freedom taken from you.”

The first time Hood, now 39, smoked weed, he was in high school in New Orleans. “It made me feel a certain kind of peace,” he says. For most of his life, he was “a massive smoker” but never a burnout. He attended some college, then worked for a judge in the court system delivering records and later as a janitor. “Where we grew up, in the Calliope projects in New Orleans, people were going to jail for murder and then coming home,” his sister Nyra Hood-Miles tells me. “For him to go to jail for marijuana of all things…We never saw this coming.”

Hood was convicted twice, in 2005 and 2009, for weed: once for distribution, and once with possession with intent to distribute. He claims he was never planning to sell it, however: “The state offered me a [plea] deal with no jail time, so I took it.” Then, in 2010, probation officers searched his house and found more than a pound of weed. He was charged a third time for possession with intent to distribute, and not offered any plea deal.

Louisiana’s three-strike rule allows judges to sentence anyone convicted three or more times of drug crimes carrying 12-year sentences to life in prison without parole. Hood knew about this law—he had worked for a judge, after all—but never expected it to apply to a nonviolent marijuana offense. Ultimately, Hood and his lawyer, John Lindner, managed to reduce the life sentence to 25 years with a possibility of parole in twelve and half years. Whether or not he receives parole is up to the discretion of the Department of Corrections.

Hood believes the most recent trial was influenced by post-Katrina racism. “The storm had caused a lot of people to move from New Orleans to St. Tammany Parish [where I was convicted]. People are conservative and they saw it as all the criminals coming in.” Though Hood himself had lived in the New Orleans suburb before Katrina, “They were trying to make an example,” he says. (Walter Reed, the DA who convicted Hood, recently declined to run for reelection after a three-decade term, amid accusations of corruption.)

Nationwide, the ACLU reports that blacks and whites are almost equally likely to use cannabis. Yet an inordinate percentage of people who end up getting arrested for weed are black, according to the report. In Louisiana, African-Americans made up 60.8 percent of arrests for cannabis possession in 2010 (though sentences as harsh as Cornell’s are rare); they make up only 32 percent of the population. The report focused solely on black-white racial disparities and did not consider other minorities, in part because the FBI does not identify Latinos as a distinct racial group in its arrest data.

On the surface, the debate over weed’s image can seem disconnected from the most important fact about the drug: It is still illegal. But the image of weed has always been entwined with its legality. As Eric Schlosser observes in his history Reefer Madness, when government officials first sought to ban the plant in the 1910s, twenties, and thirties, they played up its use by Mexican immigrants and African Americans, so-called “inferior races,” and argued that it encouraged “murders, sex crimes, and insanity.” Yet, contrary to their intentions, weed’s illegality only made it more appealing to social dissidents and rebels of all races in the next few decades.

We all know what happened in the sixties. Less often discussed is what came after, as smoking weed went from being an emblem of radical culture to a radical act all by itself. High Times’ first issue in 1974, planned as a spoof of Playboy, featured a centerfold of weed instead of a naked woman. Forty years later, the bud-shot centerfold is still going strong. Pot no longer has to be about anything other than itself to seem edgy.

When you think about it, traditional stoner aesthetics are basically one big weed centerfold. Viewed by critics, the visual culture is loud, crude and intellectually lazy. Viewed by supporters, it’s straightforward and effective at getting a message across. Even those elements of stoner culture originally conceived to be obtuse—for instance, slang like “420” and “chronic”—are no longer so, including to parents and police.

Herein lies the root of complaints about stoner taste, as well as the subculture’s claim to authenticity. Stoners are in your face, including about their support for those who suffer on weed’s behalf. By this logic, the most authentic type of stoner is he who refuses to change out of his Bob Marley T-shirt for a job interview, because he wants a boss that likes him for who he is. Maybe he doesn’t find one, and becomes an activist.

Weed’s new look, on the other hand, is demure, more vape pen than bong. It has commonalities with craft beer and organic food. It’s open to interpretation. Consider Dixie Elixirs, which sells products like THC-infused Sparkling Pomegranate soda at 450 locations in Colorado. Its aluminum bottles look like something you might buy at Dean & Deluca—perhaps a little too much. In April, Dixie was sued by a former business partner who claimed its THC-laced mints looked dangerously like candy. (Two months later, Maureen Dowd would pen a now-infamous column about a bad trip from an enticing-looking chocolate edible.)

Edward Forchion, who is black, thinks new weed aesthetics are mostly inauthentic and sometimes racist. “For the purposes of positive media spin marijuana is now being presented to the masses as medical, GOOD, and WHITE,” he wrote on his blog in 2013. “But for the purposes of criminality it’s presented as badness, attached to brown faces, handcuffed too tight.” In Colorado, anyone ever convicted of a drug-related felony cannot qualify for a license to work in the legal weed industry, making minority business owners rarer.

Hood thinks the black community isn’t doing enough to speak out. “I’m sure 95 percent of the hip-hop community indulges,” he says. “They promote a lifestyle in their music that it’s cool to use. But nobody is raising their voice to push on the issue.”

Branding, in other words, can overshadow politics, whether it’s coming from black or white communities, or in blatant or subtle forms. But it’s also integral to them. Legalization laws are being passed frequently by referendum, most recently in November in Alaska, Oregon, and D.C. What’s the best strategy for influencing public opinion? Must one “face” of weed take precedent?

These are the questions that cause flamewars, like the one spurred by Olivia Mannix’s comment about “the stoners.” During our call, Mannix speaks slowly and carefully, as if considering rebuttals that might appear in the comments section of this story. She emphasizes her respect for the diverse traditions and cultures of weed. She never mentions the word “stoner.” However, she maintains that weed needs a rebrand. “There are a lot of negative stereotypes,” she says. The stereotypes don’t come from within the culture as much as outside it, in her view. “The media tends to over-sensationalize.”

Lots of people agree: since the controversy, Cannabrand has regained as many clients as it initially lost, according to Mannix. After the fallout, Cheryl Shuman called to offer support. “I think they’re nice kids,” she says. “And I know what it feels like to be attacked.”

Cheryl Shuman

Shuman is less worried about being diplomatic, though. “I’m a ball-busting bitch,” she tells me within ten minutes of answering my call, referring to how she reacted when a group of old-school activists began lighting up in the middle of a conference she organized in Los Angeles. “Fighting the system doesn’t work,” she says. Her strategy uses connections to “media, celebrities, and high net-worth individuals” to garner support for and ultimately normalize weed.

When I compared Shuman to Forchion, I skipped over a crucial difference: Shuman has attracted far more attention from the world outside cannabis culture, as well as vitriol from the inside. She’s been profiled by the New York Times magazine and appeared on the cover of Adweek. On forums, though, she inspires so many rants it feels futile to wade through them. The erstwhile Ferrari is unpopular, as were her plans to star in a reality TV show about “high-society” cannabis users in Beverly Hills. Some of the criticisms leave an icky aftertaste of misogyny. One 3,000-word post obsessively chronicling her online activity calls her “a ragged old attention whore.”

Many of those calling for a “new face” for weed are women, and there’s a lot of blatant sexism in stoner culture to unite them. Consider the 420 nurse phenomenon. Or the fact that High Times featured porn stars on its covers throughout the aughts, with the same tone of hedonistic indulgence as the bud centerfolds. Or that companies selling products as banal as antibacterial wipes for pipes employ half-naked “Kush Girls” to push their wares at expos.

Still, not everyone agrees on which traditions to discard and which to keep. Diane Fornbacher, the owner and publisher of Ladybud, an online women’s magazine devoted to cannabis and Drug War reform, attempts to leave the question open-ended. The publication’s mission statement is illustrative: “We use smart words and fun words; we are crass, fancy—a mixture of everything. We love cannabis absolutely, or have a casual relationship with Mary Jane, and some of us don’t medicate or consume with it at all.”

“There’s no new face of cannabis,” Fornbacher tells me from her home in Colorado, a suburban house that belies her activist career. “We’re all the faces of cannabis. And a lot of us have always been here.”

What’s changed, then? If anything, “people today need a hook,” she says. “When you go mainstream, you need marketing. And we tend to remember best what’s being shouted at us.”

Cornell Hood II doesn’t shout, but his story does. Life in prison is a shocking and unusual punishment. “When the news first came out, it blew up. Lots of people and celebrities commented,” he says. When he and his lawyer managed to reduce his sentence to 25 years with the possibility of parole in half that time, it was a victory. But afterwards, people paid less attention, he says.

Most of those caught up in the Drug War don’t have unique, attention-getting victim narratives. They suffer consequences, though—losing jobs, for instance, or being barred from welfare programs. Cornell is happy to be a voice for others, he says, even if he didn’t choose to be. He understands it’s important for causes to have faces. But he’d give up that honor in a second, just to be able to sit on a porch somewhere and sip a Dixie Elixirs Sparkling Pomegranate soda. In other words, for freedom.

Alice Hines is a writer in New York. Follow her on Twitter @alicehines.

Why can’t there still be a stoner culture because some people want to market it differently than others? It’s about comfort factor and sales, and maybe some upper-middle-class woman wouldn’t want to buy weed from a shop that has the “stoner basement” feel where a more “spa-like” environment is what makes them happy? To each their own and is why there is a free market in the USA (not of weed, obv, but in general).

A subculture war almost as childish, ridiculous and annoying as the one involving Star Wars fans who are emotionally invested in the “Expanded Universe” books, comics and merchandise and the ones who stick to canon.

The racial disparities argument seemed to get trotted out late in the most recent wave of marijuana legalization efforts. My guess is that police will find other ways to harass Black males and this appeal is akin to libertarians usual meaningless sops to abortion and gay rights (we want them but will do nothing to make them happen; as long as the Christian right supports tax cuts for the rich, we’ll vote with them).

Legalized pot is very expensive and this has the effect of transforming it into a silly boutique item like cupcakes or cronuts. The products that have been developed under this “boutique” umbrella might trickle down to the stoner culture, but ordinary people who want to smoke pot but can’t afford $6 cookies aren’t otherwise going to be affected much by this.

Removed . . .

~OGD~

The ‘stoner’ was a stereotype the mainstream used/uses to stigmatize potheads. It is based wholly on the Cheech & Chong comedy bits, which yuppies & conservatives use to say “We’re supposed to take seriously people so impaired & stupid? I think not.” Before Cheech & Chong, potheads were represented by Allen Ginsburg, Norman Mailer, the Beatles & the Firesign Theater.

By the way, what the hell is peak bougie? When I look it up on the internet, it is defined as (1) a slender, flexible instrument introduced into passages of the body,(2) a Mediterranean port city on the Gulf of Béjaïa in Algeria ; or (3) a wax candle.