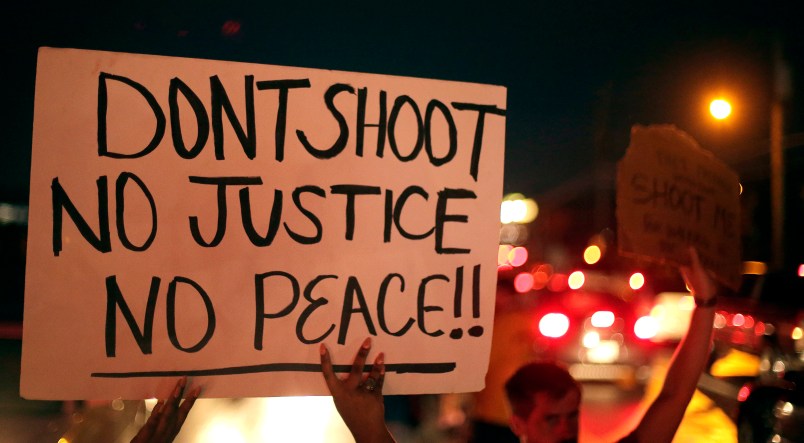

WASHINGTON (AP) — A Missouri grand jury’s decision to spare police officer Darren Wilson from criminal charges is the latest in a long line of police shooting investigations that show the latitude afforded law enforcement in using deadly force.

The question for the panel that decided the case was never whether Wilson fatally shot 18-year-old Michael Brown, but rather whether the Aug. 9 killing constituted a crime. In declining to indict Wilson, the grand jury followed laws and court precedents to reach a conclusion that is far more the norm than the exception.

“For a cop to be indicted and especially to be convicted later of a crime in these kinds of situations is very, very unusual,” said Chuck Drago, a police practices consultant and former police chief in Oviedo, Florida.

States and police departments have developed their own policies that generally permit officers to use force when they reasonably fear imminent physical harm. The Supreme Court shaped the national legal standards that govern the use of force, holding in a 1989 decision that the use of force must be evaluated through the “perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight,”

Since then, the court system has more often than not sided with police in shooting investigations, with prosecutors and grand jurors reluctant to second-guess their decisions.

Many of the cases that don’t result in charges involve armed suspects shot during confrontations with police. But even an officer who repeatedly shoots an unarmed person, as was the case in Ferguson, may avoid prosecution in cases where he reasonably believed himself to be at bodily risk.

“A police officer is not like a normal citizen who discharges their weapon. There is a presumption that somebody who is a peace officer, and is thereby authorized to use lethal force, used it correctly,” said Lori Lightfoot, a Chicago lawyer who used to investigate police shootings for the police department there.

But even though police are legally empowered to use deadly force when appropriate, Lightfoot said an officer’s perception of danger can be strongly influenced by the race of a suspect, particularly in a community like Ferguson, where an overwhelmingly white department patrols a majority-black city.

“Take any environment you live in — if there’s not diversity in your workplace, that is a void in your experience,” she said.

The Ferguson shooting followed a skirmish that began when Wilson told Brown and a friend to move from the street onto the sidewalk. Wilson told jurors that he backed his vehicle up in front of Brown and his friend, but that as he tried to open the door, Brown slammed it shut, according to testimony released after the decision.

The officer said he pushed Brown with the door and Brown hit him in the face. Wilson said Brown grabbed the gun, and that he felt the need to pull it because he was concerned another punch could “knock me out or worse.”

The Justice Department is continuing to investigate the shooting for evidence of a potential civil rights violation, and federal investigators are relying on the same evidence and witness statements as the grand jury. But they face a higher burden of proof to establish whether Wilson willfully deprived Brown of his civil rights.

That standard has been tough to satisfy in past high-profile shootings. Federal prosecutors, for example, declined this year to charge officers who fatally shot an unarmed woman with a baby in her back seat after a high-speed car chase from the White House to the U.S. Capitol.

It’s hard to know how often police use force. A federal Bureau of Justice Statistics study found that an estimated 1.4 percent of the nearly 60,000 U.S. residents who reported having contact with police in 2008 said the officers used or threatened to use force against them.

Some cases, of courses, do result in criminal charges.

A Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina, police officer was indicted in January on a voluntary manslaughter charge in the fatal shooting of an unarmed man who wrecked his vehicle and knocked on the front door of a home seeking help. Thinking incorrectly that the man was trying to break into her home, the woman who answered called police. Three officers responded and one repeatedly shot the unarmed victim, authorities say.

But far more often officers aren’t prosecuted.

A grand jury in Ohio, for instance, declined to indict a police officer who in August shot a man carrying an air rifle inside a Wal-Mart. And in May, an Alabama grand jury declined to indict an officer who shot and wounded an Air Force airman he pulled over on the highway. The Opelika police chief said the officer shot the man after he got out of his car based on a perceived threat.

Geoffrey Alpert, a University of South Carolina criminologist, said only a “small tip” of police shootings are considered so outrageous as to merit criminal charges. An absence of prosecution, he said, does not mean that an officer did a good job, didn’t make a mistake or should not face a wrongful-death lawsuit. But criminal charges are a different burden.

“He may not do (his job) well, and he may have made a mistake, but it’s not like he woke up in the morning and said, ‘I’m going to go out and kill someone,'” Alpert said.

____

Follow Eric Tucker on Twitter at http://www.twitter.com/etuckerAP

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

“A police officer is not like a normal citizen who discharges their weapon. There is a presumption that somebody who is a peace officer, and is thereby authorized to use lethal force, used it correctly,” said Lori Lightfoot

Well perhaps Lori can cite the law that supports her claim. That mindset, that cops are “super people”, is the problem. As long as cops can shoot and then claim they “felt” the need to do so people are going to die needlessly. It’s amazing that even though shooting and killing a citizen is anathema to the purpose of a cop folks are OK with it.

That’s sick. In the Ferguson shooting the office had options other than shooting. We all know that. It’s unlikely he actually felt threatened by a young man running AWAY from him. But the “Lori Principal” prevails and this man sworn to protect and serve the public shoots and kills a member of that public. I do hope Wilson lives in fear and loathing for the rest of his life. He knows what he did. Thank God he will have to live with it everyday for the rest of his life. And all he need do is look at the streets today. That anger is waiting for him. The community “feels threatened” by him…and I guess will have to act out of that fear.

I am sure there are good cops and good priests. Unfortunately it seems these positions of authority and trust have become hidey holes for social misfits

Most people who kill someone through “not do[ing their] job well” would be facing charges for manslaughter or something similar, even if they were eventually acquitted, regardless of it being a “mistake.” If the police are going to be entrusted with the powers and authority that we, as a society, grant them they should be held to a higher, not lesser, standard.

Most killings are not done by people who wake up in the morning and decide to kill someone. Policemen are just people with a job that authorizes them to carry guns (in this country, but not all countries). Very few of us carry guns, so very few of us can make a decision, while on the job, to kill someone and actually do it. Anyone who has that power has to be held to a very high standard of behavior. The fact that police in some countries don’t carry guns, but still do their jobs very well, means that a good policeman doesn’t have to shoot anyone. When there are options to shooting someone, all of those options have to be used first, and shooting has to be the last thing to be tried.

I believe that a significant percentage of people who choose to be policemen do so in order to exercise power over others. It is that attitude that leads to them killing people.

I can’t help feeling that laws written intentionally with loose language like the word “reasonable”, are often the most dangerous and misguided types of laws, which do little to define the necessary specifics in a law. It leads to a wide range of responses, subjective in nature, which predictably gives way to so much malfeasance and abuse when employed, or used in service to what most likely is a crime. All those “Stand Your Ground” laws seem to use the same language of “reasonableness”. Its a weasel word, replacing evidence based accountability. “Reasonable” is always in the eye of the beholder. Meanwhile, it would seem obvious that a dead person cannot tell their side of the story, leaving all reasonableness as a one-sided affair. How can what is “reasonable” be an objective standard for holding people accountable for their actions? Its too subjective and fraught with misinterpretation and over-interpretation imo.