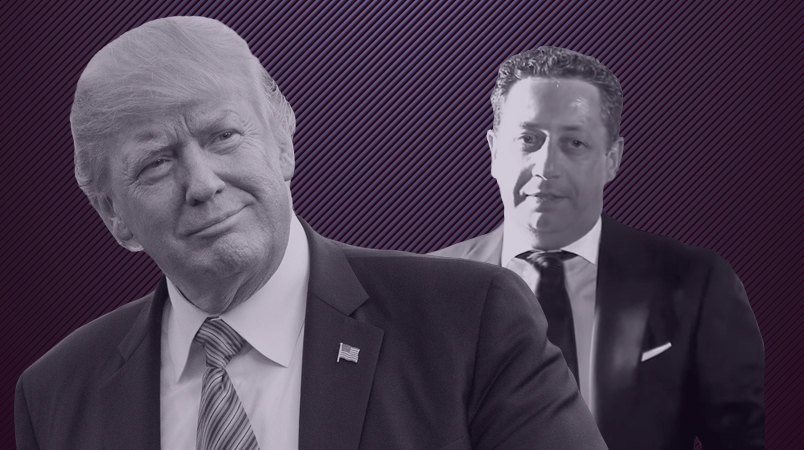

Donald Trump never seems to remember he allowed two men convicted of securities fraud to sell his name to real estate developers on three different projects.

Trump’s selective memory is just another confounding aspect of his long-standing relationship with one of his primary finance partners through the Bayrock Group, Felix Sater. His efforts to distance himself from Sater stretch back a decade, even as Sater claims that he continued to work on Trump projects until as recently as late 2015. Even after Trump took office, Sater was involved with floating a purported plan for a Russia-friendly foreign policy toward Ukraine to the administration by way of his childhood friend, Trump lawyer Michael Cohen.

In December 2007, Trump was shocked! to discover that Sater had a fraud conviction, he told the New York Times.

“We never knew that,” he said.

But he should have known, and he should have known Sater wasn’t the only one.

TPM has learned that in January 2007, the developer of the Trump Phoenix Plaza filed a lawsuit revealing 1998 fraud convictions for Sater and his confederate in a pump-and-dump scheme, a man named Sal Lauria, who had published a book detailing the scheme in 2003.

The suit was retroactively sealed in Arizona after having been made publicly available. The exact date of its filing—January 11, 2007—has not been reported. Perhaps it’s possible that Trump, who had worked with Sater for years at that point, was completely in the dark until the hasty sealing, but that seems unlikely.

The strangest thing about Sater’s 1998 fraud conviction is that few people beyond Sater’s immediate circle of business associates—Trump, Cohen, Lauria, the rest of Bayrock—would have had occasion to know about it. Any investor performing due diligence on Sater and Lauria would not have learned of the conviction. It stayed under seal for more than a decade, even after the Times outed Sater as a convict, forcing him to leave Bayrock; even after the cooperation agreement became a major point of contention in a subsequent lawsuit.

The veil drawn across the fraud case was so total that Trump even performed an encore of his who’s-that-guy routine years after the Times interviewed him about Sater: In a 2013 deposition for a suit in which Trump’s Fort Lauderdale development—also a Bayrock project—was accused of fraud, Trump claimed that he wouldn’t know Sater if the two men were sitting in the same room.

A Bayrock slide from a presentation, in which the Trump Phoenix is described as a project “Bayrock Group and The Trump Organization are developing.”

By that time, another lawsuit had been pending for years alleging that Sater’s failure to disclose his fraud conviction was itself a fraud. Filed in 2010, the lawsuit alleged that Sater had defrauded Bayrock investors, dating back to 2007, before the Times article. It was filed by one of Bayrock’s own finance directors, Jody Kriss, represented by a lawyer named Frederick Oberlander.

In court papers filed during the Kriss suit, Oberlander addressed Sater’s fraud conviction and the cooperation agreement that kept it secret; for that, he was referred for criminal contempt. The vigor of the court’s pursuit of Oberlander surprised many; reporter and legal blogger Dan Wise memorably referred to it as “Javert-like.”

Oberlander was not deterred: Though he no longer represents Kriss, he saw Sater as emblematic of a larger problem, and filed a second suit on behalf of the estate of Ernest and Judit Gottdiener, an elderly couple, since deceased, who had been among the victims in the original securities fraud. Sater, Oberlander said, owed them restitution, and for some reason neither he nor his associate Sal Lauria had been required to pay it. A third conspirator, Gennady Klotsman, was required to pay $40m all by himself, but because Sater and Lauria’s sentences were kept secret, Oberlander contends, their victims were never informed that they wouldn’t get their money back.

The question of why and how, exactly, the government forgave Sater and Lauria’s debts to their victims remains unanswered. Boz Tchividjian, a criminal law professor at Liberty University, was horrified at the notion that the government might use stolen property to negotiate with cooperating criminals. “Restitution is money that belongs to the victims,” he said. “The defendant has no rightful claim to stolen property.”

“National security” is a phrase that often crops up in defense of Sater. A federal prosecutor argued in court that Sater’s cooperation was so extensive it stretched all the way to Al Qaeda, a claim Sater repeated to TPM. Sater took part in “ten years of constant undercover work and arrests and indictments as well as convictions, some very extensive,” the prosecutor told the government in a court hearing transcript posted by Wise.

Oberlander has a more prosaic explanation, involving no terrorists: Sater was sentenced in secret and never had to return the money his firm had stolen; Oberlander argues, too, that the fact of Sater’s sealed conviction constitutes fraud all by itself. “My assumption here is that they were very concerned that they had given Sater an illegal sentence and were very concerned that if the fact of his conviction and cooperation got public, then there would be a whole lot of shit,” he told TPM.

Oberlander believes, too, that Trump knew about Sater’s convictions and stayed involved; indeed, it’s difficult to understand how he couldn’t have known. Thanks to Oberlander, it also became clear that Sater’s sentencing was kept secret—that did not come until 2009, to the annoyance even of the judge in the case, Leo I. Glasser, who said at the time that keeping Sater in limbo for 11 years since his conviction was in itself a kind of sentence.

“Fred Oberlander is a complete nut job and anything he says comes from a place of very deep dementia,” Sater told TPM. Sater said his entire sentence was a $25,000 fine, and that the mild sentence “should be enough [for you] to understand what the Judge thought of my national security assistance to this country.”

Sater’s lawyer Robert Wolf wrote: “Any claim by Frederic Oberlander that Mr. Sater’s cooperation was secret to avoid embarrassing the government is also pure garbage and has been uniformly rejected by every judge and every court that he has raised it.”

The judge who sentenced Sater, Leo I. Glasser, declined to provide any information that hadn’t already been reported, directing TPM to Google, but he did assure TPM that more information was forthcoming, likely in a report responding to Forbes’ Richard Behar, who has moved to unseal documents related to the sentencing. “There are proceedings, there’s one in progress now, and the motion has been made to unseal all that information,” Glasser told TPM by phone on Wednesday.

“A report I think has been made and is under seal, but I believe it will be unsealed soon,” he said. “I really can’t speak to you about it.”

Both Sater’s lawyer and Oberlander’s lawyer, Richard Lerner, expressed skepticism that any information was forthcoming related to the cooperation agreement that allowed Sater to move freely in the world of high finance on behalf of the president.

I don’t think the legal standard is even that high: known or should have known. And besides, what con artist doesn’t do due diligence on potential associates or marks?

Trump wouldn’t have been put off by all that. He’s positively attracted to louche, boundary-violating types, being one himself. But when anything like this is pointed out about an associate he’s suddenly Mr. Magoo—doesn’t remember, barely ever heard of the guy, wouldn’t know him in a room, employed him very briefly, all that. He’ll be saying that about Jared Kushner any day now, never mind Sater.

Willful ignorance is nice

The “New Yorker” Aug 21 has two nice articles, one about the dubious sides of DT’s business, the other about Julian Assange.

The later suggests, that the Russian actions against HRC were revenge for the Panama leaks, which Putin took personally as an American attack on him, his family and close associates. It was a coincidence, that the Trump campaign could be used as a tool, and a nice bonus, it cost HRC the election. Makes a lot of sense to me…

Well, of course he knew. He probably liked that about Sater.

ETA: I see @mattinpa beat me to it. Again.

I suppose it would even the playing field if I did more constructive work. But where’s the fun in that?