The state of Alabama has been accused of bringing back Jim Crow for closing 31 driver’s licenses offices in the state — including all the offices in counties where African Americans make up more than 75 percent of the registered voters — which critics say will further disenfranchise minority voters in a state that requires government-issued photo IDs at the ballot box.

The backlash Alabama is now facing reflects the state’s long history of blocking African Americans access to the polls, from 1965’s Selma protests that ushered in the Voting Rights Act in the first place to the 2013 Supreme Court decision in the Shelby County case that gutted a key provision of it.

The latest episode involves Alabama’s widely criticized voter ID law colliding with a broke government that can’t fund basic services. State officials are now on the defensive, denying that the closures — many of them in counties in what is known as Alabama’s “Black Belt” — will make it harder for African Americans to vote.

“The criticism is strictly a liberal attempt from people who are not from here, and don’t understand what’s going on with our people or our budget situation, they’re trying to use that to bring attention to our state in a negative light,” Secretary of State John Merrill (R), Alabama’s top elections official, said in an interview with TPM last week. “We’re doing everything we can and we are continuing to do everything we can to ensure that everyone in our state has the opportunity to do that, according to the law.”

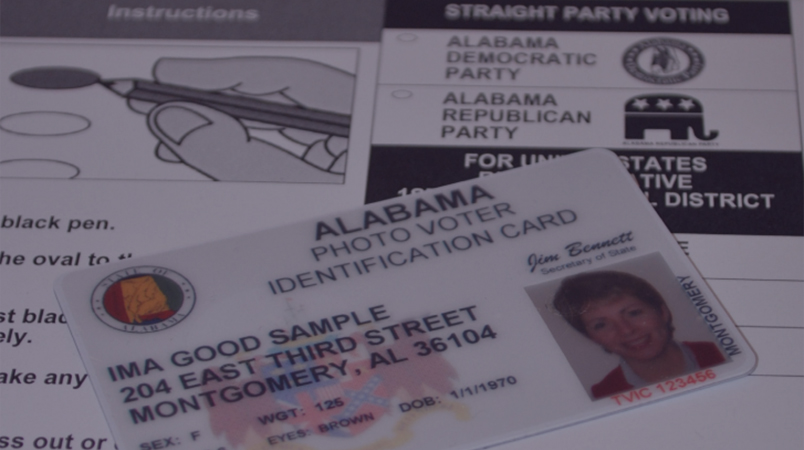

The law — which Merrill, then a state representative, voted for in 2011 — tightened voter ID requirements already on Alabama’s books by requiring a government-issued photo ID and excluding the non-photo forms, like a Social Security card, that were previously accepted. Under the new law, which only went into effect in 2014, only a handful of forms of ID, including driver’s licenses, meet the requirements.

Civil rights groups vehemently opposed the legislation, noting that these IDs are harder to obtain for minorities, who among other things are more reliant on public transportation. A state analysis showed that 500,000 registered voters lacked a driver’s licenses around the time the law was being put into effect.

Defenders of the law say those residents without driver’s licenses can obtain a free state-issued voter ID card. The free voter ID card is available from the local board of registrars, which are typically located in each county’s courthouse, from the secretary of state’s office in the state capital, or from a mobile site that travels around the state. However, so far, only a few thousand voters have obtained the voter ID card.

“You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink,” Merrill said, explaining that the mobile site has visited 56 of the state’s 67 counties at least once and will make it to all of the counties by the end of the month. He also pointed to public education campaigns — like a video campaign with some of the college football coaches in the state — to inform residents of the ways they can obtain the required IDs.

“We can show you how we have attempted to accomplish this goal, but the fact that people don’t get them, that’s not our fault.” Merrill said, pushing back at criticisms that people might not be thinking about getting a special ID months before the next election.

“You don’t think about needing to know how to swim until you’re drowning, do you? You need to learn how to swim before you get in the water.”

The way Merrill sees it, the closures will cause “a real inconvenience” for those seeking driver’s license, but have no bearing on Alabamans’ ability to vote, since the 67 boards of registrars remain open.

“The bottom line is it’s harder to drive, it’s not harder to vote,” he said. “And I don’t think any of your readers care about how many of these people are driving.”

Voting rights activists view the DMV closures as a bad situation getting worse for voting access. The satellite offices that are closing were only handling 5 percent of Alabama’s driver’s license transactions. But many of the offices that are being shuttered were already only operating a few hours a week — as highlighted by a 2012 Brennan Center report — and even before the closures, Alabama’s African American population faced particular challenges in getting licenses

“The problems that we already found are just going to be made worse by what they’re doing now,” Brennan center counsel Jonathan Brater told TPM last week.

Merrill acknowledged that driver’s licenses seemed to be the most common IDs for voters to use.

“Most people use their driver licenses when they’re going to vote, sure, but that’s not what’s required. There are a number of different items that are provided by the law that allow you to vote. The [state] ID is one of them,” Merrill said. “I don’t know why people don’t have driver’s licenses, except that they don’t drive. Maybe some of them can’t drive, but I don’t know.”

Photo illustration by Derick Dirmaier; photo credit: Alabama secretary of state’s office.

Struck a nerve with voting rights activists? No. Struck a nerve with every American who cares about fair play, equal opportunity, and civil rights.

How anyone, ANYONE, can defend such an action speaks volumes about the current racist iteration of the Republican party.

The south will always remain the south: harassment of all minorities, justified by some dumb verse from some bible.

Ok then, Let’s celebrate the Day of Jubilee, declared by the Justices of the Supreme Court…we don’t need no stinking laws to protect voting rights…

"… the fact that people don’t get them, that’s not our fault.” Merrill said. Hey Merrill: The fact that people need to get voter IDs in order to vote – for no good reason other than suppressing their votes – that part IS your fault. Close the offices as budget requires. Repeal the voter ID law and save money on your stupid “mobile site” as well.

Alabama, goddam!

(I´m sure Nina Simone wouldn´t mind the borrowing in this case.)