Not seeing is believing, at least in the case of what’s reportedly the world’s first demonstrated cloaking of a three-dimensional object.

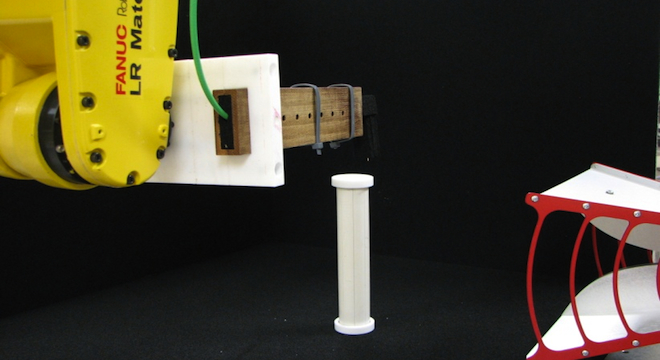

Scientists at the University of Texas in Austin (UT) on Wednesday published a paper in the New Journal of Physics describing how they managed to cloak a 7-inch-long cylinder from every angle from a microwave scanner. The objects can still be seen from the human eye, but the team says they are working on improving the effect to make the objects truly invisible to a human observer.

“This object’s invisibility is independent of where the observer is,” Dr. Andrea Alu, a professor of electrical engineering at UT and one of the paper’s co-authors, told Wired’s Danger Room. “So you’d walk right around it, and never see it.”

Previous displays of cloaking, by contrast — such as the “mirage effect” that captivated the Web’s attention in October 2011 — only achieved cloaking of a two-dimensional surface. Walk around the cloaking field and you’d see the object.

That’s not the case with what the UT scientists devised, though: They’ve managed to demonstrate it is possible to cloak any 3D object from an observing microwave scanner’s point of view, even when close to it.

But Alu and his team haven’t actually managed to cloak the object from the visual field quite yet, only from being detected by microwave scans around the 3 GHZ spectrum.

Microwave view of the UT’s cloaking effect. The first and fourth rows correspond to frequencies at which the cloak performs poorly. The second row (3.1 GHz) shows the lack of near-field scattering at the design frequency. The third row (3.3 GHz) corresponds to the upper-band edge of the cloak’s performance.

They’re working on expanding the effect to more wavelengths, including that of visible light, which would render it actually invisible to the naked eye from all 360 degrees.

“Broadening the bandwidth is a relevant issue, which we are working on right now,” Alu wrote to TPM via email.

Another issue is the size. Humans would be a bit too be big to be cloaked using the current technique devised by Alu.

“For larger sizes, any passive cloaking technique has inherent limitations,” Alu said. “We are exploring venues to increase the size of the objects to be cloaked and the bandwidth of operation.”

Still, it’s worth noting how far the team has come: Back in 2009, Alu and his collaborators demonstrated 2D cloaking using the same technique. In 2010, they published a paper explaining that it was theoretically possible to cloak a 3D object, but it took them about half-a-year to achieve the desired effect.

Alu and his fellow researchers managed to achieve the 3D cloaking using “plasmonic metamaterials,” synthetic materials consisting of alternating pieces of metal and insulation that have ultra-small differences in shape, smaller than than the wavelength of light.

When light hits non-transparent 3D objects, it scatters, and some of it bounces back to our eyes, allowing us to see them.

When light and energy of other wavelengths strike plasmonic metamerials, though, they act as though they were passing through glass rather than an opaque, solid material. That’s because the tiny features of the plasmonic metematerials surpress the natural “scattering effect” that occurs when energy, like light, strikes an object.

“The field [of energy] goes through the object and the cloak, as if they were made of the same transparent material (think of glass),” Alu told TPM via email.

Still, it’s worth pointing out that UT’s Applied Research Laboratories, where some of Alu’s team works, receives most of its research funding from the Department of Defense. That means that if and when they develop an actual unseeable-to-the-human-eye invisibility cloak, it’s probably going to be less like Harry Potter’s than the Predator’s.