Like several other Alabama sheriffs, Morgan County’s Ana Franklin has been accused of taking advantage of an archaic state law to pocket taxpayer funds set aside to feed inmates.

But the allegations against the county’s top law enforcement officer go much further.

The venture in which Franklin invested the inmate food funds happened to be a used-car lot run by an ex-felon. Franklin has failed to account for the unaudited, tax-exempt money she raised running an annual local rodeo, which earned about $20,000 each year — funds she promised went to charities and law enforcement. Most troublingly, Franklin is accused of enlisting her office to help bring charges against two people who sought to expose her.

A Morgan County Circuit judge ruled last week that Franklin and one of her deputies engaged in “criminal actions” by misleading the court in seeking a warrant to raid the office of a local blogger who has meticulously tracked Franklin’s activities.

Franklin has denied wrongdoing, writing on Facebook on Sunday that her reputation is being unfairly “defamed and torn apart.”

Amid a reported investigation by the FBI, Franklin, who took office in 2011, has announced she won’t run for re-election.

But she has no plans to step down before the end of her term.

“So far as I know, there has been no request to resign and she’s not going to resign,” one of her lawyers, William Gray, told TPM.

Used inmate food funds to invest in sketchy used-car lot

In 2015, Franklin invested $150,000 in Priceville Partners, a used-car dealership owned by an ex-felon, Greg Steenson, who spent time in jail on conspiracy and bank fraud charges.

Though her daughter and father both worked on the premises, Franklin denied knowing about Steenson’s criminal history. The following year, the dealership filed for bankruptcy and Steenson was arrested on new charges of theft and forgery involving the dealership.

During the bankruptcy proceedings, Franklin admitted that the money she invested in the lot did not come from her savings and retirement accounts, as she had originally claimed. Instead, as local blogger Glenda Lockhart documented, it came from the account earmarked to feed inmates in the prison she oversaw.

Lockhart published cashier’s checks and deposit slips on her blog, the Morgan County Whistleblower, that showed that Franklin withdrew $160,000 from the food fund account in June 2015, and that Priceville Partners deposited some $150,000 a few days later.

Franklin violated court order as inmates claimed to go hungry

As it turned out, Franklin’s use of the food funds for personal ends was forbidden. While most sheriffs in Alabama are legally permitted to keep what they deem to be excess food funds, Morgan County’s sheriff, until recently, was not. In 2009, after Franklin’s predecessor pocketed $212,000 while exclusively feeding inmates corn dogs twice a day for three months, a judge imposed a federal consent decree requiring that all of the county’s inmate food funds actually be spent on food.

After the Priceville scandal broke, Franklin said she had received poor legal advice and was unaware she could not keep excess funds. She also claimed the food served in her prison was healthy and plentiful.

That claim conflicts with findings from the Southern Center for Human Rights (SCHR) which battled Franklin in court over her violation of the consent decree last year. Court records filed by the Center describe inmates complaining of receiving inadequate, rotten, or contaminated meals.

“Detainees have complained of finding assorted matter in their food such as rocks and, in one case, a nail,” the SCHR exhibit reads. “Similarly, detainees report that meat is inedible because it is raw, beans are inedible because they have not been cooked, and bread is inedible because it is stale or moldy. Detainees have likewise complained on multiple occasions that the jail serves them food items that are frozen, sometimes with ice still attached.”

Franklin ultimately was required to pay back the $160,000 taken from the inmate food fund. She was also found in contempt of court and hit with an additional $1,000 fine.

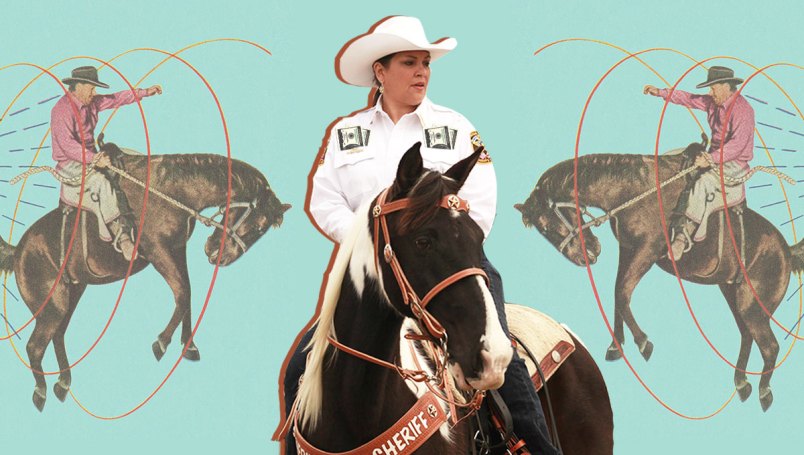

Sheriff’s rodeo fundraising proceeds went unaccounted for

Like other Alabama sheriffs, Franklin helped oversee a local sheriff’s rodeo to raise money for charity and local law enforcement. Notably, as The New York Times reported, rodeo money is not audited by the state.

Franklin told the Times that she raised $20,000 a year for charities and law enforcement, but offered conflicting accounts on where the money ended up. After the newspaper told Franklin they could find no organization by the name she first gave them, the Morgan County Sheriff’s Rodeo, she said the funds actually went to the Morgan County Sheriff’s Mounted Posse.

That non-profit happens to fall under an I.R.S. loophole for charities affiliated with government agencies, meaning it isn’t required to make its finances public, as the Times reported.

Aggressive legal action against her detractors

Franklin is accused of improperly targeting several people who have spoken out against her, most notably Lockhart, the Morgan County Whistleblower blogger.

In October 2016, Franklin paid Lockhart’s 19-year-old grandson to install surveillance software on the computer at Lockhart’s construction company to try to determine who was leaking law enforcement information to the blog. Shortly after, Franklin’s deputies obtained a search warrant and raided Lockhart’s office, seizing her computers and electronic devices.

Franklin denied allegations of retaliation, telling local press that Lockhart crossed “the line of criminal activity” in her “hateful” efforts to “tear this office down.” Lockhart promptly filed a federal suit against Franklin for violating her right to free speech, invading her privacy, and slandering her, according to court records. Lockhart has not been charged with a crime.

Caught up in the fracas was former Morgan County jail warden Leon Bradley, who was fired and, in September 2017, arrested. Franklin’s office alleged that Bradley had passed along law enforcement information to Lockhart.

In testimony for Bradley’s case, Franklin’s deputies described surreptitiously recording their conversations with Bradley and installing a GPS tracker on his car. An investigator from another Alabama sheriff’s office testified that Franklin’s office “used us” by providing inaccurate information to secure Bradley’s arrest.

Bradley’s charge was dismissed last week by circuit judge Glenn Thompson, who granted the initial search warrants. In a blistering ruling, Thompson found that Franklin and one of her deputies “deliberately misled” the court to obtain the warrants and “endeavored to hide or cover up their deception to criminal actions under the color of law.”

In a statement, the Morgan County Sheriff’s office denied any “improprieties” in the investigation.

Franklin staying put as multiple agencies probe her use of funds

The FBI is currently probing Franklin’s use of taxpayer funds, according to the the New York Times. Representatives from both the FBI and Alabama Attorney General’s office were in court listening to testimony in Bradley’s case.

But Franklin remains defiant, writing in a lengthy Sunday Facebook post thanking supporters for their “prayers” that she did nothing “criminal or unethical” and believes “the truth will be disclosed.”

Bobby Timmons, the executive director of the Alabama Sheriffs’ Association, told TPM that he personally asked Franklin to resign about three weeks ago — a claim her attorney denies.

Although Timmons said he has seen “no indication” that Franklin violated federal law, he insisted that his association holds accountable any member who “tarnishes the badge.”

“We don’t cover for ‘em at all,” said Timmons. “They know if they violate the law — taking kickbacks, getting payola from bootleggers — if they need to go to the penitentiary they’re gonna go. No sheriff is above the law.”

Is there some sort of toxic cloud hanging over Alabama that makes so many people do vile and despicable things??

Bribery of government officials particularly if they are conservative christian republican governors is already legal according to the solomonic Roberts’ Supreme Court. Why not legalize theft of taxpayer money?

If things don’t work out for her in Alabama, she could do well as the next governor of Illinois.

We can’t afford to fix the infrastructure.

-Paul Ryan

This skank just has to hire Judge Roy (hi, want to go to Chucky Cheese on a date?) Moore to represent her.