After seven years of failing to coalesce around an Obamacare replacement bill, GOP congressional leaders unveiled Monday evening legislation to dismantle the Affordable Care Act and replace it with a program that includes enough government assistance to alienate conservatives, who have called some of the proposals “Obamacare-lite,” while scaling back other coverage gains made under the ACA that could make moderate Republicans uncomfortable.

Here are 5 points on how to assess the legislation and the questions that remain:

Coverage numbers will likely go down under the Republican plan.

There’s a reason that GOP lawmakers have been stressing the word “access” as the goal of their replacement proposals, as opposed to guaranteed coverage, as was the ACA’s aim. By drastically curbing the federal government’s role in assisting Americans in their ability to get insurance, it is almost a given that coverage numbers will go down under the GOP plan.

Some 11 million people gained coverage through the law’s expansion of Medicaid, a program that will be overhauled significantly by GOP lawmakers. Under the Republican bill introduced Monday, the expanded eligibility will be allowed to continue in expansion states until 2020. At that point, the enrollment will be frozen as the larger Medicaid program is turned into a block grant, which will introduce massive cuts to its funding down the road.

More than 9 million people took advantage of the income-based tax credits offered by the ACA in 2016. Republicans are working on their own tax credits, but the details are still being hashed out. Originally they were going to adjust by age, meaning that lower and high income people would be eligible for the same credit. But Republicans have since tweaked the tax credits so that they phase out for those up the income ladder under Monday’s proposal.

The tax credits are less generous than the ACA subsidies, particularly for low income people, and people in areas of the country where premiums are higher will feel an additional squeeze, since the tax credits don’t adjust by geography, as the ACA credits do.

Republicans will reduce government spending on health care by shifting the burden of the costs.

The major driver in reduced coverage under the Republicans’ plan is how they intend to shift costs under their proposals. In the changes to Medicaid programs, those costs will be shift to the states. In the private insurance market, the burden will fall onto consumers and insurance companies (who in turn, will pass the costs to consumers).

GOP lawmakers counter that low-income people won’t need this much assistance because plans will be cheaper if Republicans are able to undo some of the market reforms the ACA imposed on insurance plans. (Whether they will be able to include those measures in their repeal bill will depend on some complicated procedural maneuvers in the Senate.)

The upshot of the GOP approach is that it could bring back aspects of insurance policies pre-ACA such as lifetime or annual caps, which placed a financial limit on what medical costs insurers were willing to cover. The approach could also lead to higher deductible plans. Republicans say that expanding health savings accounts — i.e. tax-exempt shelters for people to save for health care costs — will address that issue. But it’s hard to see how useful such accounts will be for low-income people.

Monday’s legislation would also defund Planned Parenthood by blocking Medicaid payments to certain providers that also perform abortions.

The changes to Medicaid will put states in a tough spot.

Republicans have been consistent in their desire to block grant Medicaid, but have adjusted their approach by seeking to dole out federal Medicaid funding in a per capita cap, meaning that states will get a certain amount of money for each enrollee in their Medicaid programs. A per capita cap will anticipate growth in states’ Medicaid programs in recessions or other periods where enrollment numbers are up. However, the caps do not take into account when spending in individual cases exceeds expectations, and depending on the metric lawmakers use to increase the caps over time, will not grow as fast as health care spending in general.

According to a slideshow presented by health care policy experts to governors last month, a per capita cap would result in a $584 billion cut in federal funding over the next 10 years.

In exchange for this major shift in the cost burden, congressional lawmakers are giving states more flexibility in implementing their Medicaid programs. States could raise revenues themselves via tax hikes for the program or find funding elsewhere in their budgets. Just as likely, however, is that they’ll use the permitted flexibility to limit access to Medicaid, by work requirements, cost sharing, waiting lists or other hurdles low-income people will have to jump to enroll in the program.

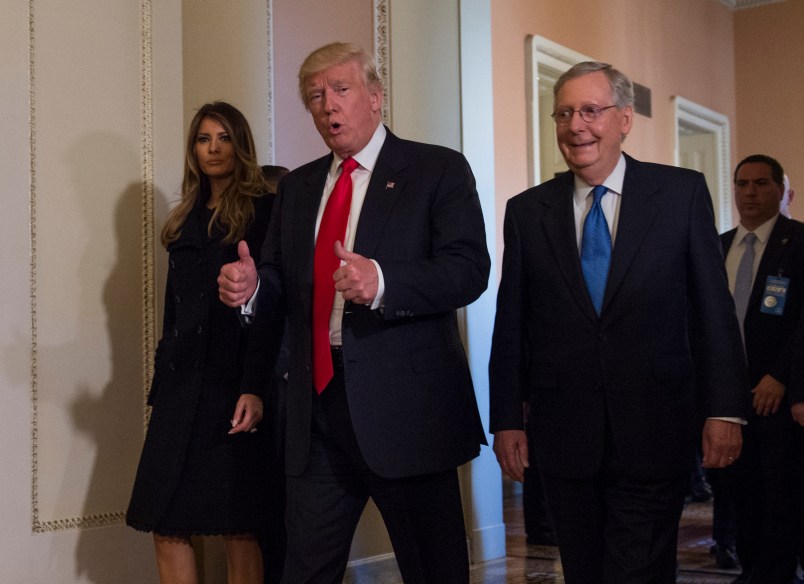

Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price, who as a GOP member of the House, previously authored the health overhaul legislation that has provided a model for Republicans seeking to repeal Obamacare.

Coverage of pre-existing conditions is a question mark.

Repealing the individual mandate — the tax penalty the ACA imposes on those who don’t get health insurance — has been on the top of the GOP’s repeal agenda, and indeed it is eliminated immediately under Monday’s bill. But how lawmakers intend to guarantee coverage for individuals with pre-existing conditions, a popular provision in the ACA that Republicans say they would like to keep, is a tricky issue without the mandate.

The point of the mandate was to drive young, healthy people to the individual market in order to stabilize the risk pools and make covering people with pre-existing conditions more affordable for insurance companies, who previously were allowed to bar them from coverage. If anything, the mandate’s penalty was too low and didn’t push enough healthy people into the market, indirectly fueling the recent hikes in premiums.

The workaround Republicans are now proposing to maintain coverage for pre-existing conditions is even more watered down. The proposal would impose what is known as a continuing coverage requirement, which would allow insurers to increase premiums by up to 30 percent for those who have let their coverage lapse for more than two months. It’s unclear whether that would be enough to incentivize healthy people to maintain insurance and pay into the system to cover the sick and those with pre-existing conditions. But it’s already catching flack from those on the far-right, who contend that the requirement is just a new form of the individual mandate. Furthermore, the provision could be stripped in the Senate, where, because of the process Republicans are using to repeal Obamacare, the legislation’s provisions must be related to the budget.

Raising revenue has become a vexing problem for Republicans

How they intend to pay for the reworked tax credits has dogged GOP lawmakers’ debates over Obamacare repeal bill. The dry-run of repeal Republicans did with 2015 legislation that President Obama vetoed last year repealed the bulk of the ACA’s taxes immediately, resulting in a major tax break for the wealthy. This time around, some Republicans wanted to keep some of the taxes to pay for a replacement, while others vehemently resisted such an approach.

Up until recently, all indications pointed to a major change to employer plans, which are used by nearly half of Americans. Under the current system, the health benefits offered by employers are not taxed like income, amounting to the largest single subsidy in the entire tax code. (The ACA’s Cadillac tax, a 40 percent levy on the most generous plans, had been delayed repeatedly.) Republicans had been contemplating capping the exclusion on employer-based plans, but the final bill released Monday had removed a cap that had been in leaked drafts of the legislation.

A report this week in the Federalist said that the CBO had estimated that the cap, coupled with a draft form of the tax credits, would shift millions off of employer-based insurance, which may be why Republicans ultimately nixed the idea.

Regardless, it now looks like lawmakers are looking primarily at cuts to Medicaid to fund their replacement provisions, while also delaying the repeal of a handful of Obamacare taxes for a few years to also bring in additional revenue (a tweak conservatives will likely abhor). Until the CBO delivers its score of the bill — which may not be until after the legislation advances out of committee — its hard to know exactly how the funding will shake out. The number of people who stand to lose coverage will become more clear after a CBO report as well.

You know how people courteously wish the opposition party to succeed for the sake of the nation? I really don’t think that applies in this case. Let us pray the GOP goes down in flames over this, finally exposed for good and all as the utter frauds they have always been.

Amen to that.

Pelosi is calling the R plan, “Make America Sick Again.”

They really can’t help themselves, can they?

How can this be allowed under reconciliation when it will almost certainly INCREASE the deficit?