It seemed that by April 30 Richard Nixon had no choice but to say something about Watergate: six Republican senators said they would not run for reelection unless he did. Young men who last month bestrode Washington like colossi were hiring lawyers under threat of indictment, leaking accusations against colleagues, writing messages on legal pads rather than speaking them aloud—who knew whether their offices, too, were bugged?

New outrages compounded daily. John Mitchell contradicted his own previous sworn testimony. Deputy campaign manager Jeb Stuart Magruder told investigators he had passed transcripts from Democratic National Committee phone bugs to the Oval Office. Chief of staff H. R. “Bob” Haldeman and domestic affairs counselor John Ehrlichman, the president’s two closest advisors, had hired criminal representation. A young staffer named Kenneth Reitz had quit his job running the 1974 congressional campaigns after it was revealed he’d run a spy shop within the Youth Division of the Committee to Re-elect the President. Pat Gray resigned from the FBI altogether after the shocking admission that he had mishandled Watergate evidence from the safe of E. Howard Hunt, which ended up in an FBI “burn bag”—containers in which sensitive materials were destroyed. The evidence, allegedly, included forged cables meant to frame John F. Kennedy for the assassination of South Vietnam’s president Ngo Dinh Diem; a spy dossier on Ted Kennedy; and a memo on Hunt’s meetings with a lobbyist linked to bribes paid to Nixon by International Telephone & Telegraph. Reporters unearthed a new private treasury of $600,000 to finance dirty tricks—like the thousands of copies of the Washington Post the White House bought, then shredded, to fake votes in a poll on whether or not the president was doing the right thing in Vietnam. “I don’t know why any citizen should ever again believe anything a government official says,” one White House staffer told Time.

Then, the staggering news at the Los Angeles trial of Daniel Ellsberg, the defense intellectual who leaked the Pentagon Papers, that on September 3, 1971, Hunt and Liddy had overseen a break-in at the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist. The burglars spoke “Cuban-style Spanish.” They worked for a unit of the White House, America now learned, referred to internally as the “Plumbers.”

A newsweekly quoted a White House staffer: “Don’t let your incredulity factor get too high—there’s more to come.” A distinguished British journalist published an op-ed in theTimes calling the United States a “banana republic.” Theodore White announced he was extending his deadline for Making of the President 1972; he needed to add a new chapter on Watergate. It grew harder to entertain the notion that the president had simply been above it all.

A newsweekly quoted a White House staffer: “Don’t let your incredulity factor get too high—there’s more to come.” A distinguished British journalist published an op-ed in theTimes calling the United States a “banana republic.” Theodore White announced he was extending his deadline for Making of the President 1972; he needed to add a new chapter on Watergate. It grew harder to entertain the notion that the president had simply been above it all.

And so he left his seclusion and, American flag peeking from behind his right shoulder, American flag pin ornamenting his lapel, a bust of Abraham Lincoln and a picture of his family beside him, explained how he was cleansing the rot.

He began, as he always did, on a maudlin note: “I want to talk to you tonight”—pause—“from my heart.” He outlined the problem: several of his closest aides, including “some of my most trusted friends,” had been accused of illegal activity in the 1972 presidential election. “The inevitable result of these charges has been to raise serious questions about the integrity of the White House itself.”

He claimed he himself had learned about the break-in: from news reports while “in Florida trying to get a few days’ rest after my visit to Moscow.” (A bid for pity: he had been working hard, making peace.) He said he had been appalled, ordering an internal investigation about whether members of his administration were involved, and “received repeated assurances that they were not.” And it was only because of those assurances from people he trusted, he said, that “I discounted stories in the press that appeared”—he emphasized the word—“to implicate members of my administration and other members of the campaign committee.”

Then he elaborated on what he had claimed two weeks earlier: that on March 21 new information convinced him he had been deceived. He addressed the audience directly: “There had been an effort to conceal the facts both from the public—from you—and from me.” So he ordered a new investigation, reporting “directly to me, right here in this office.” Those not cooperating would be forced to resign.

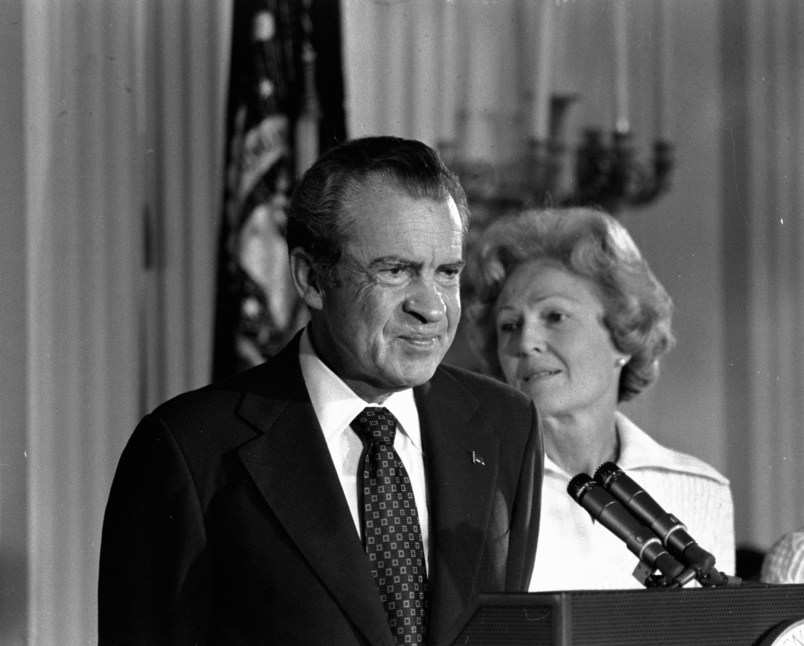

|

| Richard Nixon says goodbye to members of his staff outside the White House as he boards a helicopter for Andrews Air Force Base after resigning the Presidency Aug. 9, 1974. (AP Photo/File) |

Then came the lead for the next day’s news stories: “Today, in one of the most difficult decisions of my presidency, I accepted the resignation of two of my closest associates in the White House, Bob Haldeman, John Ehrlichman—two of the finest public servants it has been my privilege to know.” Not, he hastened to assure his audience, out of any “implication whatever of personal wrongdoing on their part. . . . But in matters as sensitive as guarding the integrity of our democratic process, it is essential not only that rigorous legal and ethical standards be observed but also that the public—you—have total confidence that they are both being observed and enforced by those in authority and particularly by the President of the United States.”

He also announced that he had let loose his attorney general, Richard Kleindienst—again, not because the individual had done anything wrong but because he was “a close personal and professional associate of some of those who are involved in the case”; and, in passing, that John Dean had resigned also. He explained nothing whatsoever about that.

There came a sort of apology. Nixon had “decided, as the 1972 campaign approached, that the presidency come first and politics second.” So “the easiest course would be for me to blame those to whom I delegated the responsibility to run the campaign.” He shook his head histrionically: “But that would be a cowardly thing to do.”

He, instead, would fight for the truth—but not let that distract him from pressing tasks like “reducing the danger of a nuclear war that would destroy civilization as we know it.”

That introduced the Checkers-style sanctimony. He listed the goals he had written on Christmas Eve for his second term. They included “to make it possible for our children, and for our children’s children, to live in a world of peace.” And: “To make this country be more than ever a land of opportunity—of equal opportunity, full opportunity, for every American.” And to “establish a climate of decency and civility.”

“There can be no whitewash at the White House,” he concluded, and asked for the nation’s prayers.

And then he absented himself from the nation’s TV screens, left to the mercy of the reviews.

The marquee editorialists granted Nixon the benefit of the doubt. The Associated Press found only two prominent critics of the speech, both Democratic governors: the left-wing John J. Gilligan of Ohio, and the Georgia moderate, Jimmy Carter. Be that as it may, just about every commentator and official of any significance united in a new consensus: Watergate was something historically awful—and the men responsible, whoever they turned out to be, were louts.

Everyone, that is, except Governor Ronald Wilson Reagan of California.

|

| Speaking to newsmen at the Winter Conference of Republican Governors’ Association in Memphis, Tennessee Sunday, Nov. 18, 1973, Governor Ronald Reagan of California said that Watergate had “hurt Democrats as well as Republicans.” Reagan also said that the Republican governors should wait until President Nixon spoke to them on Tuesday before forming or expressing opinions. (AP Photo/Paul Vathis) |

He offered his thoughts after greeting a group of high school visitors in his Sacramento reception room. Reporters asked him about speculation from Barry Goldwater that Reagan might be called to Washington to help reorganize the White House. “That’s very kind of the senator,” he answered in the third person, “but Ronald Reagan has got his hands full right here.” Then he minimized Watergate. It all was part of the usual “atmosphere of campaigning,” where pranks were just part of the game. “They did something that was stupid and foolish and was criminal”— then corrected himself: “It was illegal. Illegal is a better word than criminal because I think criminal has a different connotation.” He said, “The tragedy of this is that men who are not criminals at heart” had to suffer. It saddened him “that now there is going to have to be punishment.”

That Reagan thought the Watergate conspirators were not “criminals at heart” was the headline—“Political Spies Not ‘Criminals,’” as the Los Angeles Times put it—and a laugh line. NBC’s John Chancellor smirked, “Reagan, who talks a lot about ‘law and order,’ described the burglars as ‘well-meaning individuals committed to the reelection of the president.’” Tom Wicker used Reagan, “that exponent of law and order,” as Exhibit A in a sermon about what happens in a world run according to the Gospel of Richard Nixon, where good guys were always good no matter what they actually did, bad guys were always and everywhere ontologically evil, and no one will be safe until “ ‘we’ crack down on ‘them,’ occasionally adopting their tactics.”

Ronald Reagan divided the world into good guys and bad guys. Richard Nixon and his team were good guys. So they could not have done evil at all.

Time ran a digest on which prospects to replace Nixon in 1977 were “up” and which were “down.” John Connally, the tough former Texas governor, JFK and LBJ intimate, and Nixon treasury secretary, was looking good—he had magnanimously chosen Nixon’s difficult week to officially announce he was switching to the Republican Party. The dashing Illinois senator Charles Percy was in great shape after introducing a Senate resolution for an independent Watergate prosecutor. Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York was in good shape for his remoteness from the scandal. Ronald Reagan, however, who “put his foot in his mouth by saying that the Watergate conspirators were not ‘criminals at heart,’” was down, down, down. He had just announced that he would not be running for reelection next year, which was interpreted as a move to position himself for a presidential run. Excusing Watergate sure seemed a funny way to begin.

The notion of Reagan running for president had been in the air for years. In 1968 he made a surprise last-minute entrance into the nomination fight at the Republican National Convention in Miami—and with heavy initial support from Southern delegates—had come shockingly close to the prize. He had emerged as the hottest politician in the country. For a new issue had arisen in the second half of the 1960s, and Ronald Reagan owned it.

The issue was campus militancy. When he first starting running for governor in 1966, advisors armed with the most sophisticated public opinion research that money could buy told him not to touch it. The last thing they wanted for the candidate who costarred beside a chimp in the film Bedtime for Bonzo only fifteen years earlier was for him to associate himself with anti-intellectualism by attacking higher education. In fact, they wanted him to announce his candidacy standing beside two Nobel laureates. What’s more, they explained, the student uprising in Berkeley didn’t even show up in their polling as a public concern.

He told his experts to go climb a tree. “Look,” he lectured them, “I don’t care if I’m in the mountains, the desert, the biggest cities of the state, the first question is: ‘What are you going to do about Berkeley?’ And each time the question itself would get applause.’”

|

| Gov. Spiro T. Agnew, right, Republican vice presidential candidate, pauses to chat with Gov. Ronald Reagan, just before beginning his speech in Los Angeles at night on Nov. 2, 1968 at a $125-a-plate fund raising dinner. (AP Photo/Harold Filan) |

Ronald Reagan knew audiences. It was a key element of his political genius. One of the things at which brilliant politicians are better than mediocre ones is smelling new public concerns over the horizon before they are picked up by polls—before the public even knows to call them “issues” at all. “This is how it became an issue,” he told interviewers later. “You knew that this was the number one thing on the people’s minds.”

Berkeley: late in 1964 a police car had rolled onto the middle of the University of California’s flagship campus to dislodge a student signing up students for the Mississippi civil rights movement. Thousands gathered around the police car, trapping it, and turning it into a makeshift dais for inspiring, idealistic oratory. The “Free Speech Movement” began, and it soon became the seedbed for a nationwide antiwar movement of unprecedented breadth and intensity. In fashionable circles, the youthful energy represented by the rise of civic activism among college students was judged a tonic. Even aging Republicans got in on the act. “I think the people of your age have a function right now,” Dwight D. Eisenhower told the 1966 graduates at Kansas State University. “My generation and even those who are younger have grown pessimistic and lethargic. You people can do much for your elders.” NBC’s David Brinkley praised “a new generation of students who demand to find their own way in a society filled with social crisis.”

Reagan, on the other hand, quipped, “I’d like to harness their youthful energy with a strap.” And said he wished Congress would declare war in Vietnam, so “the anti-Vietnam demonstrations and the act of burning draft cards would be treasonable”—which is to say, punishable by death. (His own opinion on ending the war, expressed in October 1965, was “It’s silly talking about how many years we will have to spend in the jungles of Vietnam when we could pave the whole country and put parking stripes on it and still be home by Christmas.”)

Excoriating student protest came naturally to him. College was at the heart of his sentimental imagination—Frank Merriwell and all that—but it was also where he learned once and for all that heroes were not just for storybooks. “As far as I’m concerned everything good that has happened to me—everything—started on this campus,” he put it at a 1980 campaign appearance at his alma mater, Eureka College, decked out in a vintage football jersey in the school colors of maroon and gold.

Eureka: “Sounds like the name of a college in a movie,” a Hollywood columnist wrote in a 1949 profile. Dutch became aware of the little campus operated by the Disciples of Christ when his hometown hero Garland Waggoner became a football star there. He said that upon his first visit to its few modest redbrick, ivy-covered buildings, he “wanted to get into that school so badly it hurt when I thought about it.” Getting there and staying there had been no easy thing: rural America was in an agricultural depression even before the Great Crash of 1929. Then the Depression put Jack Reagan’s Fashion Boot Shop out of business. Overselling his football prowess, downplaying his B average, Reagan talked his way into a $180 athletic scholarship, paying the rest of his way washing dishes, lifeguarding, and coaching the swim team he himself helped establish. (He had never swum in a real pool before.) That made quite a contrast to the entitled brats tearing down Berkeley. Part of what made Berkeley such a powerful issue for traditionally Democratic voters was class resentment— something Ronald Reagan understood in his bones.

|

| Actor Ronald Reagan, right, gets some firsthand instruction from pitcher Bob Lemon of the Cleveland Indians at Burbank, California, December 10, 1951. Reagan has the role of Pete Alexander, the great Grover Cleveland Alexander of pitching fame, and Lemon is trying to add realism to Reagan’s task. The actor, incidentally, once played baseball at Eureka College in Illinois. (AP Photo) |

College to him meant something specific—an arena of knights-errant and blushing damsels; contests of manly derring-do; and, yes, even intellectual exploration. (Disdain for learning was one of the things that made the foppish Brown of Harvard so contemptible.) Immediately, he pledged a fraternity. (He never seemed more apoplectic during the Berkeley crisis than when he announced he had learned a left-wing professor was biased against boys wearing fraternity caps.) He scored a room in the fraternity house’s converted attic with a panoramic view of his new proving ground. (Henceforth whenever he moved into a new home it was almost always one with a panoramic view; life was more dramatic that way). And soon an opportunity to cast himself as Frank Merriwell arrived—when, three months into his freshman year, nearly the entire student body went on strike to demand the resignation of the school’s unpopular president.

No one either then or now—no attentive eyewitnesses, no diligent historians, no reporters who covered the exciting events for the Chicago Tribune, not the Associated Press, not even the New York Times—has ever been able to come up with a coherent explanation of precisely why the strike happened. Some blamed flapper-besotted students frustrated with President Bert Wilson’s refusal to lift a ban against dancing. Another theory held the opposite: the instigators were moralists annoyed at Wilson’s indifference to campus dissipation. Or that, following a trip to New York, he tried to force fancy new administrative theories on the college, which alienated his colleagues. Others note a professional rivalry with a popular professor who had been passed over for Wilson’s job (and who, according to some accounts, orchestrated the entire affair from behind the scenes, from fanning fears of staff cuts to spreading rumors that Wilson’s daughter was a sex fiend). Or maybe it was just that students were bored.

A fog of crosscutting motives and narratives, a complexity that defies storybook simplicity: that is usually the way history happens.

But not, however, in the mind of Ronald Reagan.

He made the strike the centerpiece of his 1965 memoir, writing just as Berkeley was becoming an epicenter for the national campus revolt. In Reagan’s morality tale, President Bert Wilson, Scrooge-like, had decided to impose “such a drastic cutback academically that many juniors and seniors would have been cut off without the courses needed for graduation in their chosen majors”—“cutting the heart out of the college.” Wilson then rammed the plan through the board of trustees “[w]ithout a thought of consulting students or faculty,” who both responded “with a roar of fury.”

But not, Reagan insisted, with too much fury: students responded with “no riotous burning in effigy but a serious, well-planned program, engineered from the ground up by students but with the full support and approval of almost every professor on the campus.” (“I get a bit smug when I contrast that college strike to some of the . . . fevered picketing of these more modern times,” he later told a correspondent; the contrast was surely in his mind when an effigy at Berkeley bearing a sign reading reduce reagan by 10% was hung the first month of his governorship by students protesting his budget cuts.)

In his telling, students then devised a counterplan that reorganized the university according to all of President Wilson’s stated aims, which Wilson then rejected. So they raised up a petition to present to the board of directors, demanding his resignation. “The board met on the last Saturday before Thanksgiving vacation,” Reagan wrote—a dirty trick, by which they might sign off on the president’s foul deed before the students had a chance to fight it, the cuts presented as a fait accompli when they helplessly returned from vacation.

Then . . .

Every great adventure story needs a suspenseful turning point—a moment of high drama upon which everything stands or falls. And in the imagination of Ronald Reagan, nothing heightens drama better than a football game.

“The football team met Illinois College that afternoon,” he wrote. But the crowd, he said, was distracted. He presents a striking visual image: “In the second half, newsboys hit the stands with extras headlining the fact that our petition to the board had been denied. Looking back from the bench was like looking at a card stunt”—that stadium ritual where spectators hold up coordinated color cards to trace out images. “Everyone was hidden by a newspaper.” Afterward no one left for Thanksgiving. “We all remained on campus, waiting until midnight for the summit to break up.” The college bell tolled; “as prearranged as Paul Revere’s ride,” the school chapel filled with students and faculty.

Dramatically, just in the nick of time, evil was foiled.

Enters our star—a lowly freshman, just like his favorite Yale hero: “it was my turn to come off the bench. It had been decided that the motion for putting our plan into effect should be presented by a freshman.” He took the stage. He gave a brilliant speech. “When I came to actually present the motion there was no need for parliamentary procedure: they came to their feet with a roar—even the faculty members present voted by acclamation. It was heady wine. Hell, with two more lines I could have had them riding through ‘every Middlesex village and farm’— without horses yet.’ . . . In the end it was our policy of polite resistance that brought victory. After a week, the new president resigned.” And so they received “an education in human nature and the rights of man to universal education that nothing could erase from our psyches. . . . The four classes on campus became the most tightly knit groups ever to graduate from Eureka. . . . Campus spirit bloomed. A remarkably close bond to the faculty developed.”

|

| Ronald Reagan, just out of Eureka College, is shown here at radio station WOC, Davenport, Iowa, in 1932 where he announced University of Iowa football games under the name of “Dutch” Reagan. (AP Photo) |

Here is the problem: many of these events are matters of record—which contradicts Reagan’s story at almost every point. The showdown meeting took place on a Tuesday, for instance, not a football Saturday. Nobody else remembered Ronald Reagan saving the day; he appears in no contemporary newspaper account. “You know, I read that part of his autobiography on Eureka College,” a classmate told a writer decades later, “and I wondered whether he and I went to the same school. This thing is pretty dreamy.”

But it is true he did emerge shortly after the strike as an incipient Big Man on Campus. Maybe he was being honored for his ability after the event to present the fog of bureaucratic war as a simple morality tale to a confused student body, giving students the clarity they needed to bind themselves together in the wake of an acrimonious conflict. We do, after all, tell stories in order to live.

In February the freshman made his first appearance in the school paper’s gossip column: “Dutch Reagan’s debut as cheer leader in the Normal cage”—that is, at the basketball auditorium at Illinois State Normal University—“was very much in his favor . . . He was full of spirit and the Normal rooters followed him almost perfectly.” He began playing the lead in school plays; the word that reappears in reviews is “presence.” He also began wearing dark horn-rimmed glasses, like Harold Lloyd’s in The Freshman, eagerly stitching himself into the elaborate rituals of 1920s varsity life—“‘E’ Tribe”; a seventy-fifth anniversary pageant set in the “Forest Primeval”; pep rallies, in whose defense he wrote an impassioned jeremiad, signed “Dutch Reagan,” imagining sports as savior of his school’s floundering Depression-era fortunes:

“Eureka Spirit”—it is advertised and upheld as something superior to that of other schools. But is it? . . . Let’s live basketball and Eureka till Mac’s Red Devils take Illinois College in the last game of the season. It’s our year in at least three major sports. Now let’s get a freshman class in here of over one hundred and let’s go home and wake up the Christian churches to the fact that this is their school and they owe it their support. “Let’s get in there and pitch”!

In sports where he wasn’t skilled enough for conference competition, he found other ways to make himself indispensable. For instance, a classmate remembered him as the basketball team’s regular yell leader— “one of the best we’ve ever had. He turned that crowd upside down . . . a whale of a good cheerleader.” He became the football team’s tackling dummy: “Although ‘Dutch’ failed to get much competition this season he has the determination and fight to finally win out, if he sticks to football throughout his college career,” his sophomore yearbook read. “He never gives up when the odds are against him.” Maybe he wrote that; he was on the yearbook staff. Or maybe he didn’t: “He never quit,” Coach McKenzie—another new surrogate father—remembered. “Others did.” (He scored his only touchdown in a game at Illinois State Normal College, he told reporters in 1982—“lowering himself to the Oval Office floor, showing how he picked up an ISNU fumble, then lurched up to recreate a frantic romp to the end zone.”) His coach even figured into his story about why his grades weren’t impressive. Dutch claimed he flubbed them on purpose—a happy ending. “I was afraid if my grades were good I might end up an athletic teacher at some small school. I wanted more than [Coach] Mac had.”

In his junior year he added the Booster Club, and displayed an interest in international politics: on March 22, 1931, a “lively discussion over world peace and the chances of another war” was led by “Ronald Reagan, better known as Dutch . . . and as the saying goes, ‘he needs no introduction.’” By the next school year he was senior class president.

There was one college detail that only his classmates remembered; Reagan never spoke of it himself. They recalled how the Reagan brothers staged the school’s first homecoming dance—“the biggest thing seen here in years”—charging their classmates a premium to attend, and splitting the proceeds. Another recollection of a classmate that never found its way into Reagan’s self-representations: in 1932, he bet five of his fraternity brothers that within five years he would be making five thousand dollars a year. His girlfriend recalled that he told them if he didn’t make that much, “I’ll consider these four years here wasted.”

The stories he chose to tell, tell a story in themselves, as do those he chose not to.

“We had a special spirit at Eureka,” he wrote, “that bound us all together, much as a poverty-stricken family is bound”: tuition fees “made no pretense of covering the actual cost of an education,” and many students couldn’t pay the tuition anyway; the endowment was inadequate, so professors would “go for months without pay”; part of the endowment was a farm, from whose produce the school sometimes paid its debts. “Oh, it was a small town, a small school, with small doings. It was in a poor time without money, without ceremony, with pleasant thoughts of the past to balance fears of the uncertain future. But it somehow provided the charm and enchantment which alone can make a memory of a school something to cherish.” In Ronald Reagan’s recollections of Eureka there could never be anything venal (except in the person of President Bert Wilson, because he was a villain).

|

| Ronald Reagan, standing far right, is shown with other members of the student senate at Eureka College in Eureka, Ill., 1931. Reagan, known as “Dutch” on campus, was active in sports, drama and student life. Reagan graduated with the Class of 1932. (AP Photo) |

That made quite a contrast with the “multiversity”—as Chancellor Clark Kerr termed the sprawling campuses of the University of California system. Reagan traversed the state in 1966 offering an image yoking protesters who believed themselves the moral equivalent of the Founding Fathers to that varsity culture of the 1920s: “I’m sorry they did away with paddles in fraternities.” He isolated the villains: Chancellor Kerr, for entertaining the students’ grievances, and Governor Pat Brown, ex officio member of the Board of Regents, for not having immediately taken the ringleaders “by the scruff of the neck and thrown them off campus— personally.” That would “put the rest of them back to work doing their homework.” When he was governor, Reagan said, the watchword would be “obey the rules or get out.” The tactics of what they called the “New Left,” he said, better resembled that of the “Old Right,” which his generation had fought so hard to defeat—the Nazi Party.

Such perorations would get a rousing ovation every time. And that, even more than singling out alleged abuses of California’s welfare system by “able-bodied malingerers,” or his fulminations against the violation of economic liberty represented by the state’s new statute outlawing racial discrimination in housing, or high taxes and runaway government spending generally, was how he won his stunning upset victory.

Then, when it became Governor Reagan’s job to superintend the university upon his inauguration in 1967, he wrangled control of the Board of Regents in order to have Clark Kerr fired, wrested from the nine campus chancellors their final authority to appoint faculty, and instituted tuition for the first time in the system’s history. It was not the business of the state, he said, “to subsidize intellectual curiosity”—the intellectual curiosity of students whom he sometimes labeled “brats,” “freaks,” and “cowardly fascists,” but whose “academic freedom” he insisted he himself guarded as zealously as a crusading knight. Except, however, when he did not: “Academic freedom does not include attacks on other faculty members or on the administration of the university,” the former student striker once scowled on TV, “or seeking to incite incidents on other campuses.” When one of the founders of the New Left group Students for a Democratic Society was recruited to the faculty at the campus in Santa Barbara, Reagan said that was like hiring an arsonist to work at a fireworks factory.

It made him a national political star. Of the sixty-seven times Reagan was featured on the three network newscasts between 1967 and 1970, more than half concerned his stance on campus militancy. For instance, in the fall of 1968, a Berkeley faculty member recruited Black Panther Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver as guest lecturer for Social Analysis 139X—Dehumanization and Regeneration in the American Social Order. Reagan said if it happened he would investigate the school from “top to bottom”—for “if Eldridge Cleaver is allowed to teach our children, they may come home one night and slit our throats.” Cleaver taught anyway, proclaiming in one lecture, “Ronald Reagan is a punk, a sissy, and a coward, and I challenge him to a duel to the death or until he says Uncle Eldridge. I give him a choice of weapons—a gun, a knife, a baseball bat, or marshmallows.”

After the Reagan-controlled Board of Regents rebuked Cleaver, a 1,500-student march culminated in the holding of a dean hostage. Reagan, on ABC, scowled: “The calls and the letters make it pretty clear that the people have reached the end of the line, and I don’t blame them.” When school opened the next semester, San Francisco State College students demanding a new ethnic studies program blockaded campus buildings. Reagan answered with soldiers bearing fixed bayonets. Tear gas flew back and forth, and bonfires illuminated the streets. On NBC Reagan said that the “small group of criminal anarchist and latter-day fascists” whom he held responsible—those who “seek to close down the campuses, our universities, and even our high schools,” a goal which was “not in any way to be confused with the traditional and generally acceptable activities of students who always seek change through proper and constructive channels”—would soon receive their comeuppance: “Those who want to get an education and those who want to teach should be protected at the point of a bayonet if necessary.”

The next month, the same movement surfaced at Berkeley. He visited the campus for an inspection; a throng started chanting “Fuck Reagan”; the governor responded with an outstretched middle finger. Students shattered the glass door of the building where he was meeting.

It was then that a CBS reporter confronted him with an apparently irrefutable argument: every time he escalated such deployments, conflict only escalated. Reagan responded with the logic of Frank Merriwell at Yale: he was rescuing damsels in distress. “When you see a coed, a girl trying to make her way to class, and she is pushed around, and physically abused for trying to go through the picket line and go to class,” he said, “this girl is entitled to have the forces of law and order to defend her right to go to class.”

The reporter stood silent, incredulous. He had no idea what this strange man was talking about. Though this strange man, it had to be said, was then enjoying the highest approval ratings of his term.

Later that spring, when Berkeley students forcefully seized a spit of vacant campus land and declared it a “People’s Park,” Reagan dispatched not just National Guard troops but a Sikorsky helicopter that spewed tear gas at students cornered into a crowded campus square. A student was shot observing events from a rooftop. Reagan said, “The police didn’t kill the young man. He was killed by the first college administrator who said some time ago it was all right to break the laws in the name of dissent.” His address at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco defending the military deployment—he was beating back, he said, “a revolutionary movement involving a tiny minority of faculty and students finding concealment and shelter in an entire college generation. . . . Stand firm and the university can dispose of this revolution within the week”—made all three networks.

The following year, as bomb scares swept the nation following the conviction of seven New Left activists for conspiring to disrupt the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, UC Santa Barbara students burned down a Bank of America branch. Marx-minded student leaders welcomed such incidents as “heightening the contradictions”—a necessary precursor to the longed-for revolution. Reagan barked back, four days before the shootings at Kent State: “If it’s to be a bloodbath, let it be now. No more appeasement.”

|

| Undercover police drag a spectator past an overturned car near Chicago’s Grant Park following an outbreak of skirmishes between police and fans attending a rock concert, July 27, 1970. Grant Park was the scene of clashes between police and demonstrators during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. (AP Photo/Fred Jewell) |

Hard to know how a politician could bounce back from that in an election year. Or so said his detractors. Instead, he won reelection overwhelmingly. Life profiled him that fall as “The Hottest Candidate in Either Party,” noting, however, that Reagan had “failed almost completely to keep his campaign promises of 1966—the cost of higher education and welfare has risen hideously, California campuses have remained battlegrounds, and his ‘tax reform’ has been turned down in the legislature.” Life’s quotation marks signified skepticism about how a tax plan that delivered most benefit to upper incomes counted as reform at all. And yet, even more than in 1966, he attracted thousands of Democrats who’d never imagined voting for a Republican before in their lives. “His most effective campaigners,” Life explained, “have been those college-based Reagan haters who rioted over People’s Park in Berkeley and set fire to the Bank of America’s branch in Isla Vista last spring.”

A fat lot of good that would do him in 1973, went conventional wisdom, now that the Paris peace settlement had put Reagan’s most effective campaigners out of business. A political cartoon told the story: an archaic-looking hippie, like something from another age, held up his picket sign with a peace symbol in one hand and a placard reading unemployed in the other. Reagan couldn’t even count on the loyalty of Republican conservatives, either: their hearts belonged, as their bumper stickers proclaimed, to “Spiro of ’76.” And there was this: Vice President Spiro Agnew would be fifty-six at convention time. John Connally would be fifty-nine. Chuck Percy would be fifty-six—and Reagan, at sixty-five, would be eligible for Social Security. “Around the mouth and neck,” George Will of National Review wrote, “he looks like an old man.”

Ronald Reagan’s closest political advisors had been meeting for weekly breakfasts, racking their brains on how to move him into the front ranks of presidential contenders. The plan they arrived at was announced the week after the end of the Vietnam War. Bad accounting and an improving economy had left California with a nearly $1 billion budget surplus. Reagan said he intended to “return the money to taxpayers”— novel language at the time. His method would be unprecedented: the state’s first ballot initiative sponsored by a sitting governor. The state made a tactical decision the pundits called ill-advised: to put it on the ballot for November 1973, instead of in 1974. It set off an apparently impossible scramble to get six hundred thousand signatures by June to get it on the ballot. The plan baffled the pundits. George McGovern had made middle-class tax relief a centerpiece of his presidential campaign only a few months earlier; that, obviously, had gone nowhere. The details of the plan devised by four right-wing Reagan advisors—economist Milton Friedman, Martin Anderson, a lawyer named Anthony Kennedy, and Chief of Staff Edwin Meese—were confusing. The aim was to put a ceiling on state taxes and spending. But it seemed to bestow most of its favors on those who were already well-off—and what sort of political sense did a giveaway to the rich make for Ronald Reagan? sneered the Los Angeles Times in a May 16 article about allegations that state employees were gathering signatures while on the job. It pointed out revelations that the governor had paid no state income tax in 1970, because of “so-called business losses,” and noted his decision to lift a moratorium on offshore drilling in effect since a disastrous 1969 Santa Barbara Channel oil spill. The Democratic state assembly leader Bob Moretti pounced, calling the proposal “economic war on the interests of people in California.”

Reagan had a response for that: he was defending an innocent maiden called “the taxpayer” against a devouring beast called “government.” He asked, “Are we automatically destined to tax and spend, spend and tax indefinitely, until the people have nothing left of their earnings for themselves? Have we abandoned or forgotten the interests and well-being of the taxpayer whose toil makes government possible in the first place? Or is he to become a pawn in a deadly game of government monopoly whose only purpose is to serve the confiscatory appetites of runaway government spending?”

His opponents scratched their heads at that, too. If Sacramento housed such profligate spenders, why did the state budget have a surplus in the first place? If confiscatory taxes were the aim, why were there no tax increases on the table in the legislature?

Be that as it may, Ronald Reagan was back on the national news once more.

A CBS reporter addressed the camera from the front porch of a clearly gobsmacked housewife, her luxurious home surrounded by perhaps two dozen newsmen and camera operators: “No, it wasn’t the Fuller Brush Man making the rounds in Los Angeles this morning. . . .”

“Hello, how are you, it’s Ronald Reagan!”

“What a surprise! Wonderful!”

The reporter broke in: “Reagan’s problem is that the California legislature has refused to buy his plan for cutting taxes, so the governor was out ringing doorbells getting signatures to bypass the legislature. . . .”

“All right! I’ll sign!”

Then next door: “Hello, Mrs. Marshman.”

Mrs. Marshman literally swooned: the advantage of a matinée idol in politics.

“Reagan wants to roll back California’s present personal income tax and ease the future tax bite with a constitutional ceiling on state spending. But his critics are already charging that the stakes are more personal, that the California tax reduction is simply Reagan’s first move in an all-out campaign for the Republican presidential nomination. Bill Walker, CBS News, Los Angeles.”

Nationally, however, the electorate’s attention was elsewhere.

Nightclub comics, lapel buttons, and bumper stickers told the story: “Four more years? Maybe ten to twenty.” “Don’t Blame Me. I voted for McGovern.” “Free the Watergate 500.” Nixon’s approval ratings plunged below 50 percent for the first time. Ministers frantically rewrote their Sunday sermons on “Watergate morality” to keep up with cascading revelations: the indictments of John Mitchell and campaign fund-raiser and former Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans; news that the judge in the Ellsberg case had been offered the FBI directorship as a bribe; White House ties to the forged Diem cables—and the imminent debut of live coverage on May 17 on all three networks and PBS of Senator Ervin’s Watergate hearings.

Yet here was Ronald Reagan on May 15 releasing a statement to reporters awaiting his appearance at his regular press conference: “Now that the Watergate controversy is under federal investigation, and is before a grand jury, the courts, and the Senate, I will make no further statement regarding any of the individuals involved.” Because, he said, they were “none of my business.” And not much of theirs, either—for Watergate was being “blown out of proportion.”

The reporters were astonished. There was something comical about this genial ostrich standing before them, peddling fairy tales in a time when serious moral reckoning with the failings of America’s governing institutions was entering the national political conversation as never before.

What they did not recognize was that maybe he was onto something. The previous year, when that entrepreneur in New York announced he would be republishing Frank Merriwell novels as “the country’s guide and measuring stick as national singularity is restored,” the national media mocked him. Things proved different that spring when a major paperback publisher brought out a long-buried Horatio Alger novel called Silas Snobden’s Office Boy. The New York Times featured it in not one but two decidedly nonpatronizing articles: one found its invitation to an “Eden before Eve” “filled with startling relevances”; the other said, “If it has never been your good fortune to experience pure innocence, then reading an Alger novel is as good a substitute as you will find.” A seller’s market in innocence was emerging. What the jacket copy advertised as a “LOST TREASURE CHEST OF CHARM AND NOSTALGIA” was just the thing “to rouse the memories of the old, the wonder of the young, the ire of the cynics, and the conscience of post-Watergate America.” The Los Angeles Times welcomed, at long last, a novel with “no subtle characterizations, no crises of identity, no dark nights of the soul, no whining about fate.” Publishers Weekly pronounced it “a delight.”

It was around then, three days after the Ervin hearings began broadcasting live, that the Democratic electoral analysts Richard Scammon and Benjamin Wattenberg asked in theWashington Post, “Does Watergate have coattails?” Possibly not, they concluded. According to the Harris Poll, by a margin of 73 to 15 percent, voters agreed, “Dirty campaign tactics exist among both the Republicans and Democrats. And the Nixon campaign people were no worse than the Democrats, except they got caught at it.” Maybe they were satisfied with what Nixon had told them two weeks earlier. Maybe they preferred ostrichlike innocence. The Senate hearings would tell.

From THE INVISIBLE BRIDGE by Rick Perlstein. Copyright © 2014 by Rick Perlstein. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Rick Perlstein is the author of Nixonland.

What’s the point - and what’s new? Reagan was a harder, later to national politics and more publicly appealing version of what Nixon represented: the reaction to the bruising of America’s ego in Vietnam, to the Civil Rights Movement and Black rebellion, and the “1960’s culture.” It was the Democrats that greased the way for Reagan’s ascendancy with the nomination of the “born again” religion-espousing, anti-welfare peanut farmer Jimmy Carter. Perlman’s chapter doesn’t offer anything substantially new (if anything new at all). Demagogically playing an outsider to those in power is SOP in American populist-style conservative politics (and capitalist politics generally - it was part of Hitler’s appeal).

Bravo to Rick. Another in his riveting series on modern conservatism in America. As this volume deals with the rise of Reagan, it’s guaranteed to be the target of much vituperation from the right (already begun).

They got just the actor they wanted, and we’re still paying the tab today.

As a child I felt sorry for Nixon. He seemed pathetic, and I was too young to understand the war. He still seems pathetic.

What followed…is God laughing at us? Or perhaps allowing our National Mean Streak to come to its inevitable conclusion to see if humanity will grow up? Or perhaps She’s finally lost patience with us and our time is up.

Anything that helps bring to the public an analysis of the right is necessary. Heck, even NPR is covering it. My good-looking namesake has a great article in Salon:

Nixon’s resignation did not usher in Reagan. Was the writer even alive in those days? Carter, in spite of probably being the most decent person to hold the office of president in the 20th Century, was naive in some ways and was faced with a shitty host of circumstances that would have troubled any presidency - inherited an economy in the toilet, the first oil embargo and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

There was a six year interval between Nixon’s demise and Reagan’s election. Nixon was definitely a Republican of a different stripe who, though a mostly repellent human being, did less damage to the nation domestically in nearly 8 years in office than Reagan did in his first four.

I was mostly right - Perlstein was born in 1969. That would be like me writing a book about how Eisenhower ushered in Nixon. He doesn’t have any idea, really, what the Nixon-Carter-Ford period was like.