It’s a phenomenon that any observer of modern U.S. politics senses, but now we have a study documenting it: Despite all the evidence to the contrary, white Americans believe that African Americans’ social progress in society is coming at their expense.

A new study conducted by a couple of professors at Harvard Business School and Tufts University reports that “whites believe that racism against whites has increased significantly, as racism against blacks has decreased.”

The report, published in the May edition of peer-reviewed Perspectives on Psychological Science, is based on a nationwide survey of 208 blacks and 209 whites who were chosen as a representative demographic sample of the wider U.S.’ population of whites and blacks, said Tuft’s Associate Professor of Psychology Sam Sommers.

Michael I. Norton, a Harvard Business School professor, was the study’s co-author.

Though the sample size seems relatively small, the professors’ thesis has provoked a thoughtful and informative discussion over at The New York Times‘ Room For Debate blog.

George Washington University’s Jeffrey Rosen predicts that if borne out, the study could herald a tilt in future Supreme Court decisions away from affirmative action.

Sommers argues that their study puts to rest the notion that Barack Obama’s election as president means that we all now live in a “post-racial society.”

“I would hope that this would disabuse people of the notion that race doesn’t matter anymore,” he said in an interview. “What we’re finding is that Americans still have very strong feelings about race.”

And we’re not just talking about certain members of the Tea Party.

We’re talking about the underlying notion that any racial preferences — such as affirmative action programs — amounts to discrimination against whites, Sommers said.

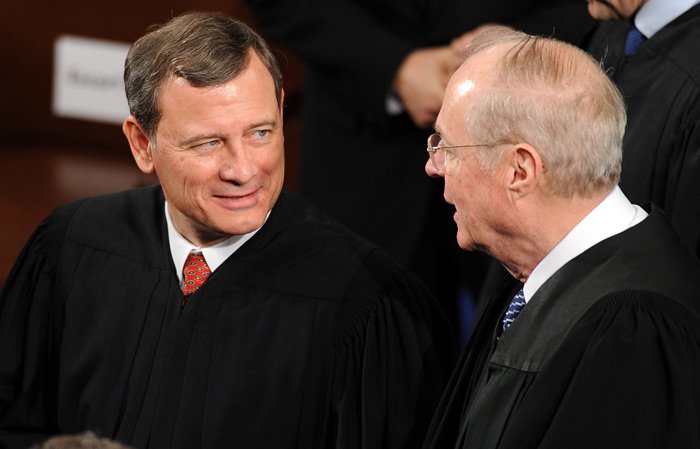

He points to the Supreme Court’s 2007 decision that stopped a Seattle school district from racially integrating its district by including race as a factor in school admissions policy.

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote the opinion, reasoned that “even though you’re trying to remedy other problems, you can’t solve the problem of racial discrimination by giving racial preferences of any form … he’s equating any sort of racial preference with discrimination, and I think the respondents in our survey are doing the same thing,” Sommers said.

The study asked both white and black participants about their perceptions of discrimination against both their own, and the other race, in each decade between the 1950s and to the 2000s.

They were asked to rate from a scale of 1 to 10 the level of discrimination that they felt was occurring against blacks and whites over those decades. One was “not at all” and 10 was “very much.”

Both whites and blacks responded similarly about their perceptions of the level of discrimination in the 1950s. But over time, the white respondents said that they believed that discrimination against themselves had increased significantly as it decreased against blacks.

What’s the upshot of this finding?

Sommers says that it flies in the face of reality — as far as blacks’ experience of the law enforcement and legal system goes. He teaches a course on the psychology of law, and the statistics on racial disparities in law enforcement and prosecution activities clearly show a bias against blacks, he said.

In addition, “economists have documented over and over again that it takes twice as many resumes to get a call back from an employer if you have a black-sounding name.”

That’s a troubling finding for politics, and it most probably explains and documents why politicians so often pander and make some of the policy decisions and speeches that they do when the facts so clearly argue that the opposite decisions should be made.

Sadly, it merely builds on prior research that shows that voters tend to stick to their beliefs even when they’re shown facts that disprove them.