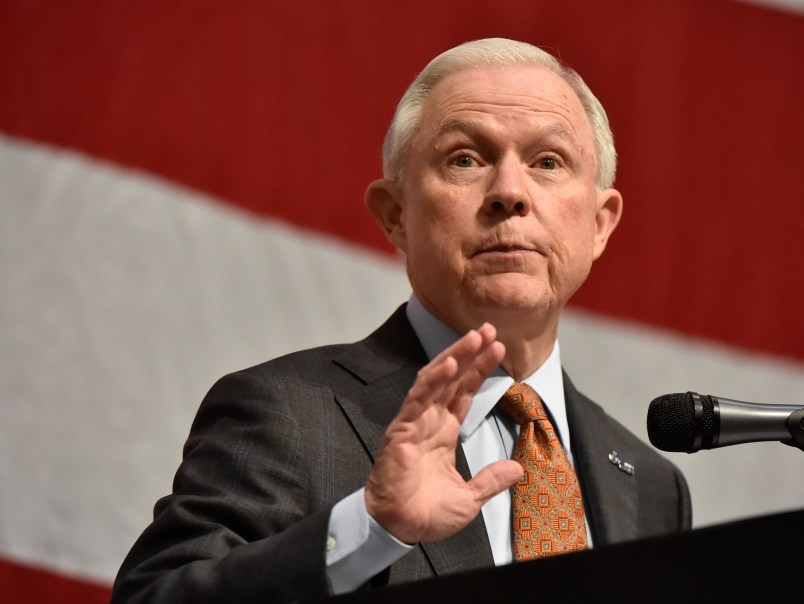

A procedural scuffle between Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) brought back to the forefront accusations that Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL), President Trump’s attorney general nominee, sought to prosecute voter outreach efforts in black counties in Alabama earlier in his career.

The episode during Sessions’ time as a U.S. attorney was among the concerns that sunk Sessions’ nominations to a federal judgeship in the mid-1980s, and it was brought up again by Democrats during Sessions’ attorney general confirmation process. Tuesday evening, Warren attempted to read from the Senate floor a letter from the late Coretta Scott King, a civil rights activist and wife of Martin Luther King, Jr., in which she accused Sessions of using “the awesome power of his office to chill the free exercise of the vote by black citizens.”

“Mr. Sessions sought to punish older black civil rights activists, advisers and colleagues of my husband, who had been key figures in the civil rights movement in the 1960’s,” King wrote in 1986. “These were persons who, realizing the potential of the absentee vote among blacks, had learned to use the process within the bounds of legality and had taught others to do the same. The only sin they committed was being too successful in gaining votes.”

Warren’s recitation of the letter was shut down by McConnell, who invoked an arcane Senate rule that prohibits senators from impugning the.character of other senators from the chamber’s floor.

The voter fraud case, which the feds embarked upon after Alabama’s 1984 state elections, sparked attention nationwide and remains a flash point as Sessions is considered for the post that would put him in charge of civil rights protections in the United States.

“It was the first and most celebrated of a string of Justice Department cases that charged black civil rights activists in rural Alabama with ballot-tampering,” the Washington Post wrote in 1986.

Civil rights groups saw the case as a return to Jim Crow and to pre-Voting Rights Act tactics, such as literacy tests, designed to discourage African Americans from voting.

“The actions taken by Mr. Sessions in regard to the 1984 voting fraud prosecutions represent just one more technique used to intimidate black voters and thus deny them this most precious franchise,” King wrote.

The case targeted three prominent civil rights activists in Alabama: Albert Turner, an MLK aide who marched in Selma; Turner’s wife, Evelyn; and Spencer Hogue, another activist. Under Session’s supervision, they were charged with a 29-count indictment. A jury cleared them of all charges after a mere four hours of deliberation, according to an AP report from the time.

After the verdict, Sessions said the activists’ lawyer “put on a brilliant defense and whipped us fair and square in the courtroom, but I guarantee you there was sufficient evidence for a conviction.”

The investigation began with the FBI monitoring a meeting of Turner and the other activists at a local post office the night before the September 1984 Democratic primary, according to a 1985 New York Times report. The federal agents recorded the names and addresses of the 500 absentee ballots that Hogue mailed after the meeting, according to the Times. The feds got a judge’s permission to open the ballots on Election Day to determine who they voted for.

Civil rights groups accused the feds of targeting black counties in Alabama, where black voters had recently achieved enough political power to elect African Americans to local office. They argued that absentee ballot-collection had long been used in white counties, and no such voter fraud investigations were being conducted there.

“We will respond to any substantiated charge of vote fraud against whites or blacks,” Sessions said at the time of the trial, according to a 1985 Chicago Tribune report. “I know of no charges against white election officials in my jurisdiction.”

Court documents included the testimony of voters who said theirs or their family members’ ballots had been changed, the Chicago Tribune reported. The activists’ defense team — led by Robert Turner, Albert’s brother — alleged that witnesses had been pressured by the FBI to testify against the activists, the AP reported at the time. The defense contended that the voters were bused 200 miles to testify before a grand jury in Mobile, when they could have testified at a location much closer.

“These voters, and others, have announced they are now never going to vote again,” King wrote in her letter.

According to the Washington Post, the case fell apart when some of witnesses changed their accounts on the stand.

King’s letter was sent to Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-SC) as the Senate was weighing Session’s nomination to a judgeship by President Reagan. His confirmation was also bogged down by allegations by a DOJ colleague who said Sessions smeared civil rights groups and expressed racist sentiments. The Senate Judiciary Committee ultimately rejected his nomination.

Thurmond never put the letter in the congressional record, and its absence was noted again as Sessions was being considered for attorney general, until the Washington Post obtained a copy of it.

During Sessions’ testimony in his confirmation hearings last month, various Trump transition team fact sheets were handed out challenging the accusations against the senator, including those surrounding the voter fraud case. One of the articles cited, “How Black Democrats Stole Votes in Alabama and Jeff Sessions Tried To Stop It” by George W. Bush DOJ alum Hans Von Spakovsky, countered that the investigation had been spurred by complaints by black residents, and particularly by two black Democratic candidates who were political opponents of Turner.

Robert Turner testified at the time, according to the Miami Herald, that there were two political factions in their county, and that Sessions “went after one (pro-black) and left the other (pro-white) alone.”

He’s a racist bigot from way back and probably still is, what’s to discuss?

Thanks for the quotes from the letter, TPM. They formed the body of my “guess what everybody is reading today” fax to McConnell.

And that’s my problem with Sessions. I don’t have a problem with someone who acknowledges that they screwed up, who apologizes for their prior behavior, who has demonstrated by word and deed that they are no longer that individual.

None of this applies to Sessions, who appears to be today precisely who he was at that time.

And things haven’t changed much since. Except now they make laws to prevent this horrible, wide-spread “tampering” before it can happen, so they don’t need racist US Attorneys to trump up charges. Of course, if (when?) this asshole gets confirmed, they’ll be right back to 1986.

Not 1986. Try 1865.