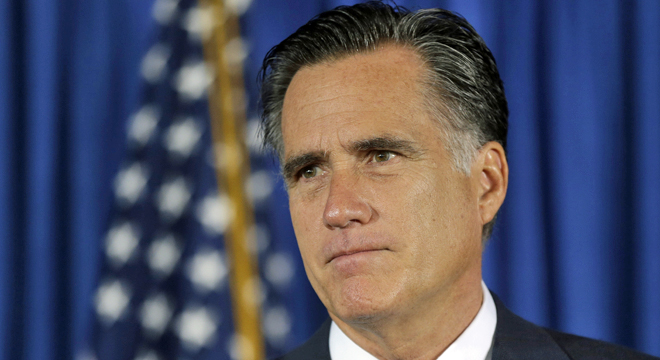

In an interview with the Columbus Dispatch in Ohio published Thursday, Mitt Romney repeated a claim that already got him in trouble once this cycle and has reflects an enduring belief among Republicans: that people in the U.S. don’t die because they lack health insurance.

“[Y]ou go to the hospital, you get treated, you get care, and it’s paid for, either by charity, the government or by the hospital,” Romney said. “We don’t have people that become ill, who die in their apartment because they don’t have insurance.”

It’s eerily reminiscent of a statement President George W. Bush made in 2007 that haunted Republicans during the 2008 campaign — “[P]eople have access to health care in America. After all, you just go to an emergency room.”

There’s just one problem: It’s not true.

Numerous studies over the past 10 years conclude that tens of thousands of Americans die each year because they lack insurance.

A 2009 study conducted at Harvard Medical School and Cambridge Health Alliance, and published in the American Journal of Public Health concluded that “[l]ack of health insurance is associated with as many as 44,789 deaths per year in the United States, more than those caused by kidney disease. … The increased risk of death attributable to uninsurance suggests that alternative measures of access to medical care for the uninsured, such as community health centers, do not provide the protection of private health insurance.”

A 2012 report by the health care reform advocacy group Families USA concluded that 26,100 people died prematurely in America in 2010 due to lack of insurance. That report extrapolated from a 2002 Institute of Medicine study — conducted when the uninsurance rate was lower — which concluded that 18,000 people died prematurely because they weren’t covered.

In a 2009 update, the IOM concluded that uninsured patients are at higher risk of mortality or poor health outcomes in the aftermath of both acute medical issues (heart attacks, serious injury, stroke) and chronic ones (cancer, diabetes).

In 2008, the Urban Institute’s Stan Dorn concluded that “[b]ased on the IOM’s methodology and subsequent Census Bureau estimates of insurance coverage, 137,000 people died from 2000 through 2006 because they lacked health insurance, including 22,000 people in 2006. Much subsequent research has continued to confirm the link between insurance and mortality risk described by IOM. In fact, subsequent studies and analysis suggest that, if anything, the IOM methodology may underestimate the number of deaths that result from a lack of insurance coverage.”

Conservatives have attacked these findings and methods and argued that, controlling for health status, there’s no difference in survival probabilities between insured and uninsured people. When the Families USA report came out, Avik Roy, a Romney health adviser, called its findings “statistical hogwash.”

To buttress his argument, he cited a thorough study by Richard Kronick — a University of Rochester health policy expert who served in the Obama administration and was a senior adviser to Bill Clinton during his push for health care reform. His conclusion? “[I]f two people are otherwise similar at baseline … but one is insured and the other uninsured, their likelihood of survival over a 2-16-year follow-up period is nearly identical.”

Further, I show that survival probabilities for the insured and uninsured are similar even among disadvantaged subsets of the population; that there are no differences for long-term uninsured compared with short-term uninsured; that the results are no different when the length of the follow-up period is shortened; and that there are no differences when causes of death are restricted to those causes thought to be amenable to the quality of health care.

However, Kronick conceded that “[g]iven the inherent uncertainties in inferring causality from the results of observational analyses, the results presented here are not able to provide a definitive answer to the question, ‘How many fewer deaths would there be in the United States if all residents were continuously covered by health insurance?'”

In an interview, Urban’s Stan Dorn praised Kronick but defended his and his colleagues’ conclusion.

“I’m aware of Rick’s study and he’s a great researcher. And I guess what I’d say is it’s an outlier,” Dorn said in an interview. “There’s a lot of research that goes beyond what we did, and it’s an outlier.”

Dorn noted that other studies focusing on particular ailments make the link between uninsurance and death quite clear. “We know that women with cervical cancer who are uninsured get their cancer detected later…. We know that people with heart disease don’t take their medicine because they can’t afford it…and sometimes die.”

And as Boston University health economist Austin Frakt noted when he engaged this same controversy in February 2010, “among recent studies in this area the evidence is greater than three-to-one in favor of an insurance-health outcome link, including mortality.”

In 2006, then-Massachusetts governor Romney himself agreed — at least to an extent. Though he did not address the mortality issue specifically, in an April 2006 presentation before the Chamber of Commerce he conceded that uninsured people who seek health care at emergency rooms experience worse outcomes.

“There ought to be enough money to help people get insurance because an insured individual has a better chance of having an excellent medical experience than the one who has not. An insured individual is more likely to go to a primary care physician or a clinic to get evaluated for their conditions and to get early treatment, to get pharmaceutical treatment, as opposed to showing up in the emergency room where the treatment is more expensive and less effective than if they got preventive and primary care.”